11

Jan

Honey Bee Losses Impact Food System and Economy

(Beyond Pesticides, January 11, 2012) On January 10, beekeepers from across the country gathered at a national conference, with environmental organizations at their side, to draw attention to the growing plight facing their industry —the decline of honey bees, a problem that has far reaching implications for the U.S. economy. The disappearance of the bees alerts us to a fundamental and systemic flaw in our approach to the use of toxic chemicals -and highlights the question as to whether our risk assessment approach to regulation will destroy our food system, environment, and economy.

“Bees and other pollinators are the underpinnings of a successful agricultural economy,” said Brett Adee, Co-Chair of the National Honey Bee Advisory Board and owner of Adee Honey Farms. “Without healthy, successful pollinators, billions of dollars are at stake.”

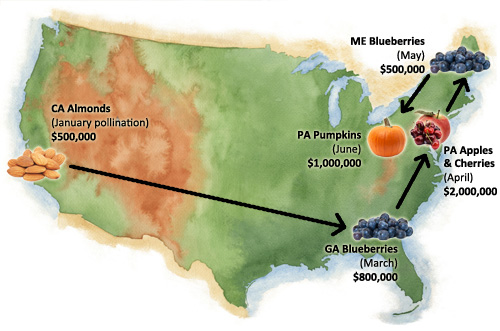

Many family-owned beekeeping operations are migratory, with beekeepers traveling the country from state-to-state, during different months of the year to provide pollination services and harvest honey and wax. Bees in particular are responsible for pollinating many high-value crops, including pumpkins, cherries, cranberries, almonds, apples, watermelons, and blueberries. So any decline in bee populations, health and productivity can have especially large impacts on the agricultural economy (see factsheet).

Honey bees are the most economically important pollinators in the world, according to a recent United Nations report on the global decline of pollinator populations.

“Because EPA has not adequately regulated certain pesticides, the food system, including many of the foods we enjoy eating most, are at risk,” said John Kepner, Project Director at Beyond Pesticides. “We can’t afford not to take action to protect pollinators —for wallets and dinner tables alike.”

On Tuesday, commercial beekeepers shared first-hand accounts of the value of beekeeping, and of the dramatic impact of bee declines. Beekeepers estimate that one single bee kill from a pesticide exposure incident, representing 200 bee colonies, is responsible for an estimated $5 million of value to the agricultural economy. David Hackenberg, Co-Chair of the National Honey Bee Advisory Board and owner of Hackenberg Apiaries, estimates that his colonies alone generate $5 million in value over six months: $500,000 from California almonds in January, $800,000 from Georgia blueberries in March, $2 million from Pennsylvania apples and cherries in April, $500,000 from Maine blueberries in May, and $1 million from Pennsylvania pumpkins in June.

“If you think about it, bees and other pollinators are Mother Nature’s ultimate economic stimulus,” said Mr. Hackenberg. Economists quantify pollination as an ”˜ecosystem service’ although these figures are often unaccounted for in the traditional measures like the GDP.”

In 2000, the last official study, the value of pollination was estimated at $14.6 million. Beekeepers suggest number that under-calculates the value of their services. They suggest the real value of their operations is $50 billion, based on retail value of food and crop grown from seed that relies upon bee pollination.

Beekeepers have survived the economic recession only to find their operations are still threatened. Recent, catastrophic declines in honey bee populations, termed “Colony Collapse Disorder,” have been linked to a wide variety of factors, including parasites, habitat loss, and pesticides.

“The threats facing pollinators should raise concerns, as sub-lethal impacts on bees are more serious than we had initially thought,” said Dr. Jim Frazier, professor of Entomology at Penn State University. “Every time someone looks, they find something new.”

Beekeepers also note they are partnering with environmental organizations, highlighting the threat of pesticides to the continued success of the profession and the agricultural economy. They raise special concerns with neonicotinoids, a class of systemic pesticides that is taken up by a plant and expressed through the plants that bees then forage and pollinate. Research released last week in the journal PLoS ONE underscores the threat of these pesticides through a previously undocumented exposure route —planter exhaust— the talc and air mix expelled into the environment as automated planters place neonicotinoid-treated seeds into the ground during spring planting.

“Independent research links pollinator declines, especially honey bees, to a wide range of problems with industrial agriculture, especially pesticides,” said Paul Towers, spokesperson for Pesticide Action Network.

Threats to pollinators, especially commercial honey bees, concern the entire food system. With one in three bites of food reliant on pollination, beekeepers and environmental organizations alike call out the wide-scale problem.

For more information on pesticides, honey bees and other pollinators, including tips on what you can do, see Beyond Pesticides Protecting Pollinators program page.