10

May

EPA Finds Atrazine Threatens Ecological Health

(Beyond Pesticides, May 10, 2016) Following an apparent accidental release of documents relating to the safety of the herbicide glyphosate, late last month the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also released and then retracted a preliminary ecological risk assessment of another toxic herbicide, atrazine. Under federal law, every pesticide registered in the United States is required to undergo a 15-year registration review to analyze human health and environmental impacts and determine whether the chemical’s use should continue another 15 years. The last decade and a half have seen plethora of studies underscoring that atrazine is harmful to human health, and poses unreasonable adverse risks to ecological health, despite attempts by its major manufacturer, Syngenta, to silence and discredit its critics.

EPA’s preliminary ecological risk assessment finds that for current uses at prescribed label rates, atrazine may pose a chronic risk to fish, amphibians, and aquatic vertebrate animals. Where use is heavy, the agency indicates that chronic exposure through built-up concentrations in waterways is likely to adversely impact aquatic plant communities. Levels of concern, a wonky equation that EPA produces to measure risk, were exceeded for birds by 22x, fish by 62x, and mammals by 198x. Even reduced label rates were expected to harm terrestrial plant species as a result of runoff and drift from pesticide applications. It is important to note that these impacts were seen for uses which, based on data obtained during atrazine’s last review 15 years ago, EPA considered to be “safe” when used according to label rates.

EPA’s preliminary ecological risk assessment finds that for current uses at prescribed label rates, atrazine may pose a chronic risk to fish, amphibians, and aquatic vertebrate animals. Where use is heavy, the agency indicates that chronic exposure through built-up concentrations in waterways is likely to adversely impact aquatic plant communities. Levels of concern, a wonky equation that EPA produces to measure risk, were exceeded for birds by 22x, fish by 62x, and mammals by 198x. Even reduced label rates were expected to harm terrestrial plant species as a result of runoff and drift from pesticide applications. It is important to note that these impacts were seen for uses which, based on data obtained during atrazine’s last review 15 years ago, EPA considered to be “safe” when used according to label rates.

Moreover, as part of what are known as data call-ins, where EPA requests tests used to support or reject the registration of a pesticide, the agency permits pesticide manufacturers to carry out studies on their own products. Shortly before atrazine’s most recent re-registration in 2003, University of California, Berkeley professor and scientist Tyrone Hayes, PhD was hired by Syngenta to conduct safety tests on the chemical regarding its impact on amphibian health. However, what he found was not what the company had hoped for: his experiments showed that atrazine could impede the sexual development of frogs, to put it lightly. After the company criticized his research, Dr. Hayes cut ties with the company. But he continued his research, this time releasing studies that described the effects of the chemical less gingerly, like the 2010 study, Atrazine induces complete feminization and chemical castration in male African clawed frogs, published in the esteemed journal the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. During this time, Syngenta continued to target not only Dr. Hayes research, but his personal life. (See: A Valuable Reputation, by The New Yorker). Through the discovery process on a lawsuit launched by public water utilities over widespread atrazine contamination, a list of goals produced by Syngenta’s public relations was brought to light. Goal #1: “discredit Hayes.”

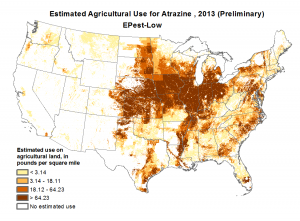

Atrazine has been registered for use since 1958. Although many residential turf grass uses of the chemical have been eliminated voluntarily, homeowner uses do persist, particularly in humid climates like southern Florida. The chemical is still widely used in agriculture, with over 90% of the chemical’s application to corn fields. Upwards of 65% of sugarcane and sorghum fields are also sprayed with atrazine, according to EPA, and it is used widely in forestry operations. In addition to reproductive impacts on amphibians, as well as studies showing similar impacts to fish, birds, reptiles, and mammals (See: Protecting Life, From Research to Regulation), the chemical has been listed to human health impacts such as childhood cancer, and rare birth defects, including gastroschisis, and choanal atresia.

As a result of a lawsuit filed by the Center for Biological Diversity, EPA will be assessing the impacts of atrazine and its chemical cousins to 1,500 endangered species, a task that the agency should have performed decades ago. Based on scientific evidence, there is no need to continue with the use of atrazine or glyphosate, especially with so many alternatives for pest management. In fact, a 2014 study published in the International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health found that banning atrazine would result in net economic benefit to farmers. EPA’s leaked ecological risk assessment, as well as the widespread availability of alternatives, shows that the risks of continuing atrazine’s registration vastly outweighs any benefits it may provide.

As consumers continue to press for reforms regarding allowed pesticides within conventional agricultural practices, the best way to support sustainable agriculture is by buying organic. Organic farmers are not permitted to use toxic synthetic herbicides or pesticides like atrazine, and must create an organic system plan to address how they will first prevent pest problems, and second, deal with them through least-toxic means should they arise. All inputs into organic farming and processing must go through a rigorous public process overseen by the National Organic Standards Board, composed of a range organic stakeholders. Although the process is not devoid of concerns, they pale in comparison to the widespread health and ecological impacts permitted in conventional agriculture.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Center for Biological Diversity, EPA Refined Ecological Risk Assessment for Atrazine