10

Apr

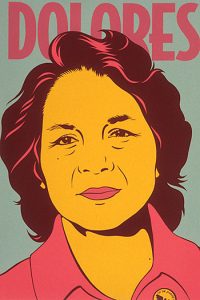

Washington and California to Celebrate First Annual Dolores Huerta Day on April 10

(Beyond Pesticides, April 10, 2019) Last month, the Washington State Senate unanimously passed HB 1906, designating April 10 as Dolores Huerta Day. In July of 2018, a similar California law proclaimed April 10 Dolores Huerta Day in that state. In an interview with Vida del Valle, Ms. Huerta stated, “I’m happy to hear that our young learners will have the opportunity to learn more about social justice and civil rights, because there is still a lot of work to do by the Dolores Huerta Foundation.”

(Beyond Pesticides, April 10, 2019) Last month, the Washington State Senate unanimously passed HB 1906, designating April 10 as Dolores Huerta Day. In July of 2018, a similar California law proclaimed April 10 Dolores Huerta Day in that state. In an interview with Vida del Valle, Ms. Huerta stated, “I’m happy to hear that our young learners will have the opportunity to learn more about social justice and civil rights, because there is still a lot of work to do by the Dolores Huerta Foundation.”

Following decades of leadership in the fight for farmworker justice, Ms. Huerta founded the Dolores Huerta Foundation in 2002, with a focus on grassroots organizing in Central Valley. According to its website, the Dolores Huerta Foundation trains low-income Central Valley residents “to advocate for parks, adequate public transportation, infrastructure improvements, the reduction of pesticide use, increased recreational opportunities, and culturally relevant services.”

“We build leadership in low-income communities and organize people so that they can have a sense of their own voices and their own power,” Ms. Huerta said of her foundation in an interview with Civil Eats. “Once they understand this process and they have the power to change policy – and politicians – they really feel empowered and they want to go on and keep organizing,” she explained, adding, “It’s wonderful. I call it ‘magic dust.’”

Dolores Huerta has been spreading this “magic dust” for over six decades.

Ms. Huerta co-founded the National Farmworkers Association – now called the United Farm Workers (UFW) – in 1962. Ms.Huerta became well known as a thought leader, organizer, lobbyist, and negotiator. As lead organizer for the historic Delano grape boycott of 1965, she convinced more than 17 million consumers to stop buying grapes in support of workers’ demands for collective bargaining rights. The boycott was as much a battle against growers as it was against the U.S. government, which interfered by purchasing grapes to send to U.S. soldiers in Vietnam. Nonetheless, the campaign succeeded, and Ms. Huerta led the negotiations that followed to secure collective bargaining agreements between the California grape industry and UFW.

Author and organizer Randy Shaw credits Ms. Huerta and her collaborators in the fight for farmworker justice for helping to lay the groundwork for “the whole idea of Environmental Justice.” “The Environmental Justice movement said that certain environmental hazards are disproportionately impacting on people of color,” Mr. Shaw explained in the 2017 documentary, Dolores. He continued, “It wasn’t simply stopping DDT, but it was also making the larger point, you’re only allowing this because of who the workers are, and their race and class background.”

That larger point came with a larger cost. “Once we started making those kind of demands, we had the same response that the Black movements had,” said Ms. Huerta of the fight for farmworker rights. “Our people were killed.” Ms. Huerta herself was brutally attacked by a crowd control police officer during a demonstration in San Francisco in 1988. She broke three ribs and had to have her spleen removed. Ms. Huerta said, “The system doesn’t really want brown people or black people to have an organization and to have real power. I found out that no matter what I did, I could never be an American. Never.”

The fight for pesticide regulation is inextricably linked to the fight for immigrant rights. “Growers don’t want [their workers] to be legalized,” said Ms. Huerta in Dolores. “Because once they’re legalized, they can protest against pesticide poisoning, they can protest against the low wages they’re being given,” she said.

To this day, Ms. Huerta is fighting for stricter regulation and a transition away from pesticide use. As stated on its website, the Dolores Huerta Foundation “organizes communities that face critical exposure to pesticides through their work in the fields and the proximity of their residence to them. . . DHF advocates against the use of harmful pesticides whenever possible.”

As Ms. Huerta points out in an interview with NPR, women and children working in the fields are especially vulnerable to pesticide poisoning: “The pesticides in the fields really affect women even more than they do men. They affect children and they affect women more than they do men.” Research indicates that exposure to common agricultural pesticides, both during development and in adulthood, is associated with increased susceptibility to breast cancer. Across the board, studies show that children’s developing organs create “early windows of great vulnerability” during which exposure to pesticides can cause lifelong damage.

Ms. Huerta represents one of many women who have been standing up for the right to healthy and safe working conditions. “There were more women involved in the UFW than probably every other labor union in the United States combined,” said author and organizer Randy Shaw in Dolores. However, many believe that Ms. Huerta was not given the credit she deserved for her accomplishments. Ms. Huerta was the only woman on the executive board during her tenure in the UFW, and several of those closest to her lament that fellow board members resisted her leadership expressly because of her gender. When co-founder Cesar Chavez died in 1993, the board chose not to elect Huerta as the new president due, many believe, to their reluctance to appoint a female leader. In August, the UFW executive board appointed union Secretary-Treasurer Teresa Romero to replace UFW’s retiring president Arturo S. Rodriguez. She is the first Latina and immigrant president of a U.S. national union.

“We’re knee deep in sexism when it comes to why she isn’t studied, and why people don’t know her,” said educator and activist Curtis Acosta, featured in the 2017 documentary. According to Mr. Acosta, Ms. Huerta publicly criticized the UFW itself for being “rife with sexism.” According to Mr. Acosta, Ms. Huerta said, “I even said to Cesar at one point in time, I said, look, we have a lot of machismo here in the farmworkers movement, and I am not going to take it anymore.” Her message to the young women and Chicana girls with whom she now works – be bold and take credit for your work.

As some of Ms. Huerta’s colleagues note, her erasure from history is not only the product of sexism, but also a testament to her continued threat to those in power. In 2010, the Texas State Board of Education removed Dolores Huerta from the state’s history curriculum. In that same year, fueled in part by Ms. Huerta’s controversial messaging to students at a Tucson school, the Arizona House Education Committee passed a bill to ban Ethnic Studies in the state. Addressing the committee at the bill’s hearing, then Superintendent Tom Horne characterized Ms. Huerta as “a former girlfriend of Cesar Chavez.” With the passage of the ban, Mr. Horne and the Education Committee struck deeper than insult – the law effectively targeted and removed a longstanding Mexican-American studies program that had empowered Tucson’s Chicano students to hold pride in their ancestry and stand up for their rights.

Though the newly designated Dolores Huerta Day will not be recognized as a legal holiday in either Washington or California, its passage provides an opportunity for education and critical reflection. The day offers an opportunity to recognize and support the work of Dolores Huerta and join with advocates standing up for justice in their communities.

As part of the 37th annual National Pesticide Forum this past weekend, Beyond Pesticides featured a panel of youth advocates for environmental justice. Stay abreast of updates on our Youtube page to learn directly from advocates how you can be a part of the movement to grow out of our oppressive present and into an ecologically and socially just future of food production.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Sources: The Cascadia Advocate, Civil Eats, NPR, Dolores Huerta Foundation, People For the American Way, Dolores (2017 film)