28

Sep

Extreme Weather Events Create Chemical Health Risks

(Beyond Pesticides, September 28, 2017) Response to the recent and powerful hurricanes that buffeted the Caribbean and continental U.S. focused first and rightly on the acute potential impacts: risks to life and limb; loss of power; damaged transportation systems; food and fuel shortages; exposure to pathogens and infectious diseases (via compromised drinking water, exposure to sewage or wastewater from overwhelmed systems, and

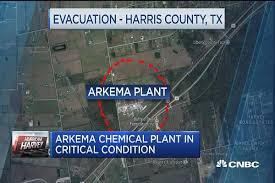

Pesticide plant Crosby, TX flooded during Harvey and 50,000 pounds of chemical exploded an caught fire.

simple proximity to other people in storm shelters); damage to and destruction of homes and buildings; and mental health issues.

Yet, as has become more evident with the experience of many ferocious and flooding storms in recent memory —Katrina (2005), Ike (2008), Irene (2011), Isaac (2012), Sandy (2012), and Harvey, Irma, José, and Maria (all in 2017)— another significant threat to human health accompanies such events. Processing and storage facilities for petroleum products, pesticides, and other chemicals can be compromised by floodwaters, releasing toxicants into those waters and the soil, and explosions and fires from damaged chemical facilities can add airborne contaminant exposure to the list of risks. The chemicals in floodwaters can also infiltrate into groundwater or water treatment systems, and some can be dragged back out to sea as floodwaters recede.

If pesticides, petroleum derivatives, and other chemicals can’t be safeguarded in the event of increasingly strong storms and other potential natural disasters, federal and state agencies must —as they currently do not— accommodate for these events in the risk calculations that inform their regulation of these compounds’ creation, storage, use, and emergency mitigation.

The Houston area, which was impacted terribly by Hurricane Harvey, may be the poster child for such toxic threats. Communities on the Gulf Coast, and the Houston area in particular, harbor many refineries and much petrochemical infrastructure. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has called the Houston area one of the most intensely contaminated areas in the country. As of August 31 this year, for example, after Hurricane Harvey hit Texas, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality reported “21 inoperable wastewater systems; 52 inoperable public water systems, serving at least 115,000 people; 18 wastewater and sanitary sewer overflows; and 184 active boil-water notices covering at least 189,000 people.”

It’s worth noting that, in addition to exposure of the population at large, first responders may suffer greater-than-average exposures. When arriving on the scene, they don’t necessarily know what they will encounter. In the longer-term aftermath of such events, emergency personnel not infrequently manifest health problems caused by their exposures to multiple —and sometimes unknown— toxic chemicals and materials.

As chemical facilities anticipate the approach of dangerous storms, they often shutter their operations to limit damage, but can release huge amounts of toxicants in doing so. In the week before Harvey made landfall, more than 2,000,000 pounds of hazardous chemicals were released into the air. “‘On a good day, there’s already a high risk of cancer,’ said Luke Metzger, director of Environment Texas, an advocacy group based in Austin. ‘This amount of pollution in such a short time just makes that risk even higher.’”

Adding to the threat are already-contaminated Superfund sites that can be compromised. EPA said on August 26 that 13 Superfund sites (of the 40–50 in Texas) were flooded by Harvey and were “experiencing possible damage” due to the storm. Floodwaters that breach such facilities contain unknown concentrations of toxicants.

Commenting on Harvey’s impacts, Michele Roberts, Co-Coordinator of the Environmental Justice Health Alliance (EJHA), said: “Victims of this storm are now facing an unacceptable confluence of environmental injustices — and if past is prologue, they will continue to face overlapping hardships for years to come. . . . Refineries and petrochemical operations in Houston, almost too numerous to count, have been venting a toxic mix of hazardous air pollutants those trapped by rising floodwaters are forced to breathe. The long-term health consequences of this toxic air pollution are unknown. . . . The concentration of only minimally regulated chemical, oil, and gas facilities in low-lying areas, combined with increasing extreme weather events due to climate change and an . . . Administration rolling back chemical safety protections and climate action — is a recipe for health and environmental disaster.”

Evidence of the risks posed by the generation, storage, and use of toxic (and often under-regulated) chemicals is legion. As Beyond Pesticides noted nearly 10 years ago, regulation of these chemicals has not kept pace with the latest science, and controversy surrounding their use continues to grow. It is not uncommon for federal and state regulators to evaluate a pesticide for 15 or 20 years while it is already in wide use, only to determine, years down the road, that its use presents unreasonable adverse effects. EPA and regulators still do not adequately evaluate the health and environmental impacts of many toxic pesticides and chemicals.

If industry cannot ensure that, during extreme weather events and natural disasters, chemicals will not migrate from their allowed sites — into waterways, groundwater, and soil — or volatilize into the air, the exposure hazards associated with these chemicals’ migration must be calculated as a risk. Regulators do not typically consider these events or other accidents as part of their risk assessments, but clearly ought to. With the increase in extreme weather events, and especially those that involve flooding and structural damage, this issue will continue to grow in importance.

In addition to the toxic chemical exposure caused by widespread chemical contamination, mosquito spray programs become commonplace over vast areas after flooding. Last week Houston announced it would douse the city with the organophosphate insecticide Naled (Dibrom), among the most potent neurotoxic mosquito pesticides on the market.

For more Beyond Pesticides background on regulation of pesticides and chemicals, please see: “Petition Filed to Compel EPA to Review All Pesticide Product Ingredients,” and “Inspector General: EPA Must Evaluate Impact of Chemical Mixtures”; for overviews from at the start of the first and second Obama administrations, respectively, see “Transforming Government’s Approach to Regulating Pesticides,” and “What a Second Obama Term Can Do to Stop the Toxic Treadmill. Beyond Pesticides also monitors regulations, at the federal and state levels, on toxic pesticides; see more at the National Watchdog web page. For general information on pesticide hazards and alternatives to their use, see the Center for Community Pesticide and Alternatives Information page.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.