21

Oct

Dietary Pesticide Exposure Study Stresses Need for More Accurate Assessment

(Beyond Pesticides, October 21, 2025) A study, published in International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, calculates cumulative dietary pesticide exposure and finds a significant positive association between pesticide residues in food and urine when analyzing over 40 produce types. The research uses data for 1,837 individuals from the 2015–2016 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) and compares them to biomonitoring samples of the participants. According to the researchers, “Here we show that consumption of fruits and vegetables, weighted by pesticide load, is associated with increasing levels of urinary pesticide biomarkers.”

They continue, “When excluding potatoes, consumption of fruits and vegetables weighted by pesticide contamination was associated with higher levels of urinary pesticide biomarkers for organophosphate, pyrethroid, and neonicotinoid insecticides.” The NHANES data is derived from a national biomonitoring survey from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which collects information about consumption of fruits and vegetables as well as urine samples.

Background

As the study authors explain: “Hundreds of millions of pounds of synthetic pesticide active ingredients are used every year in the United States, and pesticide exposure can occur through food, drinking water, residential proximity to agricultural spraying, household pesticide use, and occupational use. Pesticide usage to grow and store food often results in contamination of commodities with pesticide residues, particularly fruits and vegetables, that reach store shelves and persist after rinsing produce.” (See study here.) With that being said, dietary exposure is a critical route in which the public is subjected to pesticide residues and at risk of subsequent negative health effects, including increased risk of cancer, neurological harm, and reproductive toxicity, among others. (See the Pesticide-Induced Diseases Database (PIDD) here.)

A previous report in 1993, entitled Pesticides in the Diets of Infants and Children, set the groundwork for the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) of 1996 that “established the need for pesticide regulations to protect children’s health from cumulative toxicity associated with pesticide mixtures.” However, as the researchers point out, “the U.S. government pesticide risk assessments and legal limits for pesticides in food, also known as pesticide tolerances, generally continue to be conducted with a focus on individual pesticides and fail to consider cumulative toxic effects from exposure to mixtures of pesticides.” This data gap fails to address the potential additive and synergistic effects that can be seen with pesticide mixtures, which more realistically represents how consumers are exposed to combinations of pesticides rather than in isolation.

Study Methodology and Results

“Here, we present a methodology to rank fruits and vegetables based on overall pesticide load, including metrics of pesticide number, detection frequency, concentration, and a measure of toxicity,” the authors note. They continue: “This approach builds on the prior work of Hu et al. (2016) by incorporating pesticide toxicity reference values into the pesticide load indicator and using more recent pesticide and biomonitoring data to reflect changes in pesticide use, toxicity, and exposure.”

In ranking the commodities (produce) and their consumption, as obtained through the NHANES questionnaire, the researchers are able to calculate dietary pesticide exposure score for participants that then can be compared to urinary pesticide biomarker levels. This methodology intends to estimate overall dietary pesticide exposure and provide insight into how consuming specific fruits and vegetables might elevate urinary pesticide levels.

In addition to NHANES data, the study incorporates national pesticide residue data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Pesticide Data Program (PDP) to analyze the association between estimated dietary pesticide exposure and measured levels of internal pesticide exposure through the urine sample biomonitoring.

For each commodity from the PDP, pesticide contamination is calculated based on the detection of 178 unique parent pesticides, with 42 parent pesticides matching biomarkers in the urine samples. For more information on the methodology and statistical analyses, see here.

Biomarker concentrations of various pesticides, including organophosphate insecticides, neonicotinoids, pyrethroids, and herbicides, are detected in the urine samples. When comparing the biomarker data with the pesticide load index for the produce consumed, but with excluding potatoes due to their strong attenuating effect, a significant positive association is noted.

The researchers report: “Pesticide residues, representing 222 analytes corresponding to 178 unique parent pesticides, were detected across 44 food commodities analyzed in our study, and utilized in calculating the pesticide load indices. While pesticide residues varied greatly by commodity, the most commonly detected pesticides (>10% of samples across all commodities) were the fungicides thiabendazole, boscalid, pyraclostrobin, fludioxonil and azoxystrobin, and the insecticide imidacloprid.” The data reveals that consumption of both high and low residue fruits and vegetables is associated with increasing rank for cumulative pesticide exposure, though a single serving of high residue foods presents a greater impact.

In summary, the authors state. “Here, we developed a method to estimate cumulative dietary pesticide exposure by weighting fruit and vegetable consumption by the pesticide load for 44 different commodities, termed a dietary pesticide exposure score.” They continue, “We further demonstrated the utility of this method as a pesticide exposure metric, showing that increasing dietary pesticide exposure score, or consumption of produce, excluding potatoes, with higher pesticide load, is associated with pesticide biomarker concentrations in urine, when matching pesticides measured in produce to urinary biomarkers.”

Within the study, there are many limitations, some of which the authors address, that could impact the findings and their ability to capture the true level of adverse health impact of dietary pesticide residues. As the researchers reference, these include limited data availability and analytical limitations of the public datasets, which incorporates a lack of data on key pesticides like 2,4-D and glyphosate. Additionally, deficiencies in regulatory reviews, given the lack of complete adverse health data on endocrine disrupting pesticides as well as synergistic effects of pesticide mixtures, ultimately result in an underestimation of the harm caused by residues in the diet.

Previous Research

The current study findings are consistent with other research that identifies dietary exposure as a key contributor to measured pesticide concentrations in urine. Relevant scientific literature cited within the study includes:

- Biomonitoring studies of human urine samples identify “dozens of co-occurring exposures, and hundreds of pesticide residues have been detected in foods.” (See here and here.)

- Studies in humans link “dietary exposure to pesticide mixtures with increased risk of breast cancer, Type II diabetes, impacts on body weight, all-cause mortality, poor fertility outcomes, and cardiovascular.”

- “Laboratory animals exposed to mixtures of pesticides, often at doses below the exposure levels set by national and international regulatory agencies for which no adverse effect is expected to occur, experience health harms including decreased motor activity, changes to memory and behavior, body weight gain and impaired glucose tolerance, and reproductive tract malformations.”

- Individuals who report eating conventional food show increased levels of urinary organophosphate metabolites and higher estimated dietary exposure. (See study here.)

- Two studies (see here and here) find that “consuming high residue fruits and vegetables – notably also without considering potatoes – was associated with increasing levels of urinary metabolites for organophosphate and both organophosphate and pyrethroid insecticides respectively.”

- Research identifies associations between the consumption of high residue fruits and vegetables with lower sperm count, poorer semen quality, impacts on fertility, and increased risk for glioma. (See studies here, here, and here.)

- Pesticide mixtures of chlorpyrifos, imazalil, malathion and thiabendazole are associated with postmenopausal breast cancer risk, while mixtures of azoxystrobin, chlorpyrifos, imazalil, malathion, profenofos, and thiabendazole were associated with type two diabetes. However, “[i]n both studies, diets low in pesticide levels were associated with a reduction in risk of the studied health effects.”

- “Dietary intervention studies demonstrate that switching from a conventional diet to organic food consumption is an effective way to reduce synthetic pesticide exposure and possibly accrue health benefits.”

Benefits of an Organic Diet

As the study authors note, diet is a modifiable factor that can be adjusted to reduce exposure to harmful contaminants. Scientific literature supports a shift to an organic diet, with research finding lower pesticide residues within the body after switching to organically grown food. Previous research finds that levels of the widely used weed killer glyphosate in the human body are reduced by 70% through a one-week switch to an organic diet. (See Daily News coverage here.)

Beyond Pesticides has also reported on additional biomonitoring studies that confirm these results. See Daily News Of Note During Organic Month, Study Finds Organic Diet and Location Affect Pesticide Residues in the Body, Review of Pesticide Residues in Human Urine, Lower Concentrations with Organic Diet, and Study Demonstrates Health Benefits of Organic Diet Over That Consumed with Toxic Pesticides for more information.

In recent Daily News, organic diets promote higher cognitive scores. A study published in European Journal of Nutrition finds that consumption of organic animal-based and plant-based foods is positively associated with higher cognitive scores. Among women, there was both better cognitive function before testing (at baseline) and up to a 27 percent lower MCI [mild cognitive decline] score over the course of the study period for participants identifying as organic consumers, even if there was consumption of just one of the seven food categories. Additional health benefits of organic can be found here.

A Path Forward

In the current study, the researchers state: “Our findings suggest increased biomonitoring for pesticides is essential for public health protection. Development of analytical methods to measure internal exposure to a broader range of pesticides would also aid in understanding health effects associated with these exposures.” These authors are not the first to call for additional research and better analytical methods, but while these options may increase knowledge regarding pesticide exposure, they do not provide a holistic solution. Even scientists and advocates that stress the need for enhanced risk assessments fail to acknowledge that there is not adequate information available for accurate risk assessments that include all possible cumulative, additive, and synergistic effects from pesticide mixtures for all possible health effects including cancer and endocrine disruption. This is why many advocates call for the adoption of the precautionary principle to protect health and the environment. (See here and here.)

The data more fully confirms that pesticide reduction strategies are not fully protective of health, with this study adding to the complexities that exist in attempting to develop tools to calculate acceptable levels of risk associated with dietary exposure to pesticides. Given the efforts captured by this paper, taken together with the extensive research in PIDD and the daily tracking of scientific studies linking pesticides to cancer, birth defects, immune system disorders, endocrine disruption, sexual and reproductive dysfunction, learning and developmental effects, and nervous system implications, among others, the public can take no comfort in ‘acceptable’ levels of pesticides in food and the environment.

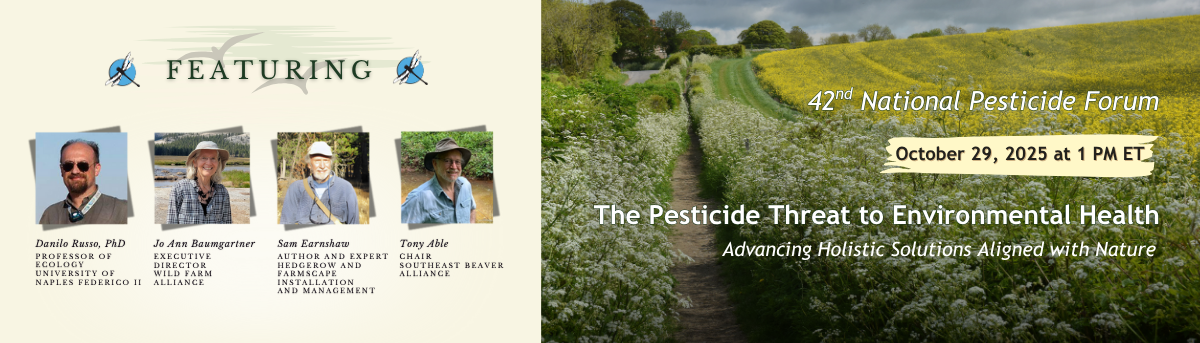

This research adds more urgency to the need to transition agriculture, and all land management, to organic systems. Visit the Eating with a Conscience database to learn more about why food labeled “organic” is the right choice. For more on this subject, consider attending Beyond Pesticides’ 42nd National Forum Series, The Pesticide Threat to Environmental Health: Advancing Holistic Solutions Aligned with Nature, which is scheduled to begin on October 29, 2025, 1:00-3:30pm (Eastern time, US) with a focus on aligning land management with nature in response to current chemical-intensive practices that pose a threat to health, biodiversity, and climate. The virtual Forum is free to all participants. ➡️ Register here.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source:

Temkin, A. et al. (2025) A cumulative dietary pesticide exposure score based on produce consumption is associated with urinary pesticide biomarkers in a U.S. biomonitoring cohort, International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1438463925001361.