13

Jul

Tick Study Leads to Inaccurate and Potentially Dangerous Pesticide Advice in Media Reports

(Beyond Pesticides, July 13, 2018) Earlier this year, a study published in the Journal of Medical Entomology by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that a known carcinogen, the synthetic pyrethroid permethrin, when applied to clothing may function as a tick deterrent. The study has led to many misleading and potentially dangerous headlines, such as National Public Radio’s story “To Repel Ticks, Try Spraying Your Clothes With A Pesticide That Mimics Mums.” These articles encourage readers to use permethrin treated clothing, and downplay the risks associated with its use. Moreover, as noted by Consumer Reports, the CDC study in question does not go as far as recommending that individuals use permethrin treated clothing.

(Beyond Pesticides, July 13, 2018) Earlier this year, a study published in the Journal of Medical Entomology by researchers at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicated that a known carcinogen, the synthetic pyrethroid permethrin, when applied to clothing may function as a tick deterrent. The study has led to many misleading and potentially dangerous headlines, such as National Public Radio’s story “To Repel Ticks, Try Spraying Your Clothes With A Pesticide That Mimics Mums.” These articles encourage readers to use permethrin treated clothing, and downplay the risks associated with its use. Moreover, as noted by Consumer Reports, the CDC study in question does not go as far as recommending that individuals use permethrin treated clothing.

The study placed ticks of different species and life stages on cloth cut from permethrin treated clothing. Researchers found that the majority of ticks had difficulty moving after exposure to the fabric. However, this effect did vary with life stages, as adult ticks were generally able handle pesticide exposure longer than nymph stage ticks. As James Dickerson, PhD, chief scientific officer of Consumer Reports notes, “The CDC’s study did not test any items while they were being worn, so it doesn’t show conclusively how well the clothes might keep ticks from biting you.” When speaking with Consumer Reports, study coauthor Lars Eisen, PhD, with CDC indicated that a larger study that includes individuals actually wearing the treated clothing is needed to indicate whether the practice is indeed effective. “We do not have that study yet,” Dr. Eisen told Consumer Reports.

NPR’s coverage of the study led it to interview an individual who recommended using both permethrin and the repellent DEET to address tick issues as “very effective,” with NPR indicating that the study backs up these claims. However, a 2001 study investigating the synergistic effects of DEET and permethrin due to its potential link to Gulf War Syndrome, reported by many veterans, found that this combination “decreased [blood brain barrier] BBB permeability in certain brain regions, and impaired sensorimotor performance.”

A U.S. Army funded study from 2011 also linked pesticide exposure and synergy to Gulf War Syndrome symptoms, singling out DEET and permethrin, among other chemicals. Despite these risks, NPR simply quoted EPA assertions that individuals were unlikely to experience “significant immediate or long-term hazard from permethrin,” but did not address synergy risks between DEET and permethrin, let alone the deficiencies in EPA’s pesticide registration system.

Beyond Pesticides strongly discourages the use of any pesticide treated clothing. In addition to being classified a likely carcinogen by EPA, permethrin has been associated with endocrine disruption, reproductive effects, neurotoxicity, and damage to organs like the kidney and liver. It’s been linked to behavioral problems in children, infant leukemia, and adverse respiratory effects such as wheezing.

In humans, symptoms of acute exposure to DEET include headache, exhaustion and mental confusion, together with blurred vision, salivation, chest tightness, muscle twitching and abdominal cramps. Researchers have noted significant concerns related to the use of DEET, including nervous system disorders, adverse developmental effects, and neurotoxicity in children. DEET poses risks to the human nervous system, according to a 2009 study. Another study associated pregnant women’s exposure to insect repellents, such as DEET, during their first trimester to an 81% increased chance of male children developing “hypospadias,” a condition where the urinary opening is at the bottom rather that the tip of the penis.

Many may also think that spraying one’s lawn with insecticides to kill ticks are a good way to address their presence around your yard. However, a study published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases in 2016 found that while these sprays may in fact kill ticks, residents that had their yard’s sprayed reported the same number of ticks and same rate of tickborne illness as those that did not. The authors concluded tick barrier sprays, “do not significantly reduce the household risk of tick exposure or incidence of tick-borne disease.”

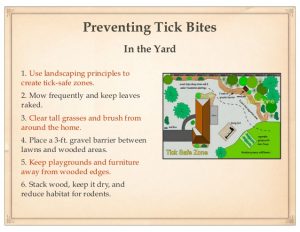

The best way to address ticks is through personal protective measures and judicious use of least-toxic repellents such as Oil of Lemon Eucalyptus, Picaridin, and IRC. If one ignores DEET from their search, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has a helpful website to find a brand of tick repellent that is effective. The website indicates the product name, length of effectiveness, active ingredient, and company name. Rather than mowed lawns, ticks are likely to hide in tall grass, shrubs, and overgrowth vegetation, and it follows that eliminating these habitats around one’s home can help suppress ticks where they’re likely to latch on. Since white-footed mice are critical vectors for tick-borne diseases like lyme, methods to reduce rodent populations can also address lyme. But if you’re going into the woods or other areas with known high tick populations, the most effective method currently is to wear appropriate clothing (light colored that covers one’s whole body), a hat, and consider tucking one’s pant’s into your socks. Most important is to conduct regular tick checks alongside a friend, as it’s critically important to detatch a tick from one’s skin as soon as possible after the bite to reduce the chance of disease transfer. If you have an outdoor pet, don’t forget to check them as well (consider a flea/tick comb and remember areas like behind the ears and in between toes).

While CDC continues to study the best methods to manage ticks, personal protection and diligence remain the best deterrents to tick-borne disease, not the use of chemicals that pose new risks to one’s health. For more information on how to manage ticks safely, see Beyond Pesticides ManageSafe webpage.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Consumer Reports, NPR, Journal of Medical Entomology

posted on behalf of M. S.:

I am so glad you wrote this article because I have the same concerns.

The product Repel Lemon Eucalyptus Insect Repellent was recommended by Consumer Reports as being effective for at least 6 hours for ticks (and mosquitoes).

Personal experience is that it works great.

Currently a study is being conducted in 24 neighborhoods in New York state using a fungus (Metarhizium anisopliae strain F52) that kills ticks, as well as TCS bait boxes. The study is called The Tick Project. https://www.tickproject.org/

July 16th, 2018 at 10:50 am