02

Jan

FDA Stops Medical Uses of Triclosan in Hospitals, Other Disinfectants to Stay Despite No Safety and Efficacy Data on Controlling Bacteria

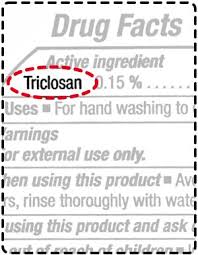

(Beyond Pesticides, January 2, 2018) The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) on  December 19, 2017 announced it was removing from the market 24 over-the-counter (OTC) disinfectants or antimicrobial ingredients, including triclosan, used by health care providers primarily in medical settings like hospitals, health care clinics, and doctors’ offices. The agency took this action because the chemical industry did not respond to a 2015 request for data to support a finding of “generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE).” The decision, which follows a 2016 FDA decision to remove OTC consumer soap products with triclosan for the same reason, leaves numerous consumer products (fabrics and textiles, sponges, undergarments, cutting boards, hair brushes, toys, prophylactics, other plastics, etc.) on the market with triclosan (often labeled as microban) under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The December decision leaves in commerce six antiseptic compounds widely used in the hospital and medical setting, in response to industry requests for more time to develop safety and efficacy data.

December 19, 2017 announced it was removing from the market 24 over-the-counter (OTC) disinfectants or antimicrobial ingredients, including triclosan, used by health care providers primarily in medical settings like hospitals, health care clinics, and doctors’ offices. The agency took this action because the chemical industry did not respond to a 2015 request for data to support a finding of “generally recognized as safe and effective (GRASE).” The decision, which follows a 2016 FDA decision to remove OTC consumer soap products with triclosan for the same reason, leaves numerous consumer products (fabrics and textiles, sponges, undergarments, cutting boards, hair brushes, toys, prophylactics, other plastics, etc.) on the market with triclosan (often labeled as microban) under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The December decision leaves in commerce six antiseptic compounds widely used in the hospital and medical setting, in response to industry requests for more time to develop safety and efficacy data.

In what appears to contradict FDA’s finding that it does not have sufficient data to make a GRASE finding for antiseptic products used in the health care and medical setting, the agency is leaving the most widely used compounds in these products on the market, under chemical industry pressure. There is wide concern that health care providers and hospitals may be using products under false and misleading labeling of products critical to patient protection from pathogenic bacteria leading to infections. Of importance is the fact that these are the most widely used products. In its press release, FDA states,

“In response to requests from industry, the FDA has deferred final rulemaking for one year, subject to renewal, on six specific active ingredients that are the most commonly used in currently marketed OTC health care antiseptic products ‒ alcohol (ethanol), isopropyl alcohol, povidone-iodine, benzalkonium chloride, benzethonium chloride, and chloroxylenol (PCMX) – to provide manufacturers with more time to complete the scientific studies necessary to fill the data gaps identified so that the agency can make a safety and efficacy determination about these ingredients. In addition, the final rule does not affect health care antiseptics that are currently marketed under new drug applications and abbreviated new drug applications.”

For advocates, the speed of the federal government’s progress on regulating toxic chemicals can be glacial. The 2016 U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) narrow ban on the antibacterial compounds triclosan and (its cousin) triclocarban in consumer soap products, after arguments against them made persistently by public health scientists, environmental advocates, and members of the public over the course of the past few decades, is a case in point.

Triclosan is an antibacterial, antifungal compound used widely in more than 200 consumer products, including: personal care products (e.g., soap, deodorant, toothpaste), toys, textiles and clothes, plastics, paints, carpeting, etc. It is regulated by both FDA and EPA, though triclosan-containing cosmetic products fall under FDA jurisdiction. Triclocarban is a related antibacterial chemical, used most commonly in soaps; its structure and function are similar to those of triclosan, and like it, has toxic properties.

The common and rapid adoption of soaps with triclosan or triclocarban was based largely on a public perception that the antibacterial compounds are effective tools for safeguarding health from harmful bacteria. For years, studies have challenged the utility of the chemicals, and found that, in fact, for OTC consumer products antibacterial soaps show no health benefits compared to soap and water washing.

These compounds have been the object of a campaign and litigation by a coalition of health and environmental groups, led by Beyond Pesticides and Food & Water Watch (and targeted litigation by the Natural Resources Defense Council, to get triclosan removed from the market. After years of clamor by these and other stakeholders to ban it from consumer products, in early Fall 2016, FDA announced a final ruling on its use in consumer washing products. FDA banned 19 specific ingredients in soap products, including triclosan and triclocarban, saying they were no longer “recognized as safe and effective,” and citing risks to health and contributions to the problem of bacterial resistance. Manufacturers had until September 6 of this year to reformulate their products and remove existing triclosan products from market. The ban does not apply to washing products used in health care and food service settings.

When the ruling was announced, Beyond Pesticides executive director Jay Feldman noted, “FDA’s decision to remove the antibacterial triclosan, found in liquid soaps [its use in toothpaste went unaddressed), is a long time coming. The agency’s failure to regulate triclosan for nearly two decades . . . put millions of people and the environment at unnecessary risk [of] toxic effects and elevated risk [of] other bacterial diseases. Now, FDA should remove it from toothpaste and EPA should immediately ban it in common household products, from plastics to textiles.” During the past few years, with pressure from consumer groups and media, major manufacturers, such as Procter & Gamble and Johnson & Johnson, have quietly reformulated their consumer products without triclosan; Colgate-Palmolive removed it from liquid soaps, but continues to include it in its toothpastes.

The timeline on the status of these chemicals is extremely protracted; what follows are some highlights of the journey to the current situation. First introduced to the market in 1972 in health care settings, it proliferated during the next several decades, permeating hundreds of consumer products with virtually no government oversight. FDA first noted, in a 1974 Tentative Final Monograph, that there was insufficient evidence that triclosan was safe and effective for long-term use. (See the end of this blog post for information on effective, nontoxic approaches to health-protective hygiene.) The FDA’s Nonprescription Drugs Advisory Committee declared, in 2005, that antibacterial soaps and washes were no more effective than regular soap and water in fighting infections. In 2009, Beyond Pesticides, in partnership with Food & Water Watch and 80 other groups, submitted a petition to FDA calling for a ban on the non-medical uses of triclosan. (A companion petition was submitted to EPA.)

The agency announced plans, in 2010, to address the use of triclosan in cosmetics and other products, saying in a response letter to Massachusetts Senator Ed Markey (then a U.S. Representative) (who had repeatedly asked FDA to write regulations for antibacterial products in hand soap and EPA on other products), that recent studies “raise valid concerns about the effect of repetitive daily human exposure to these antiseptic ingredients.” FDA initiated triclosan’s registration review in 2013, announcing that it would require manufacturers to prove that their antibacterial soaps were safe and more effective than soap and water (including providing the agency with data from clinical studies to demonstrate their findings); manufacturers failed to do so. Minnesota became the first state to enact a ban on triclosan in personal care cleaning products (2014), and the European Union banned its used altogether in 2015. On the heels of that arrived the 2016 FDA ban targeted only at consumer soap products.

The narrow address of that ruling, and the decades it has taken FDA to arrive at it, galvanized a group of scientists from academia and the nonprofit world to issue The Florence Statement on Triclosan and Triclocarban in 2016. The Summary of the statement reads: “The Florence Statement on Triclosan and Triclocarban documents a consensus of more than 200 scientists and medical professionals on the hazards of and lack of demonstrated benefit from common uses of triclosan and triclocarban. These chemicals may be used in thousands of personal care and consumer products, as well as in building materials. Based on extensive peer-reviewed research, this statement concludes that triclosan and triclocarban are environmentally persistent endocrine disruptors that bioaccumulate in and are toxic to aquatic and other organisms. Evidence of other hazards to humans and ecosystems from triclosan and triclocarban is presented, along with recommendations intended to prevent future harm from triclosan, triclocarban, and antimicrobial substances with similar properties and effects. Because antimicrobials can have unintended adverse health and environmental impacts, they should only be used when they provide an evidence-based health benefit. Greater transparency is needed in product formulations, and before an antimicrobial is incorporated into a product, the long-term health and ecological impacts should be evaluated.”

Scientific evidence has demonstrated a variety of adverse health impacts of triclosan and its cousin, triclocarban: skin irritation; exacerbation of allergic response; endocrine disruption (e.g., triclocarban has been shown to amplify the activities of natural hormones, which can cause adverse reproductive and developmental effects); interference with production of the thyroid hormones thyroxine and triiodothyronine; and increased risk (for children) of developing asthma, eczema, and allergies. In addition, there is substantial evidence that broad use of these compounds promotes the emergence of bacteria that are resistant to antibiotic medications and antibacterial cleansers important in health care, thus, contributing to the extremely serious issue of antibiotic resistance in “superbug” bacteria. Many health impacts are likely still unknown.

Because 95% of the triclosan and triclocarban from consumer products goes down residential drains and into soil, groundwater, aquifers, and waterways, there is great concern about the environmental (and ultimate human and non-human health) effects of these when they are “let loose” in the environment. In studies done roughly a decade ago, triclosan was one of the most frequently detected compounds (and at some of the highest concentrations) in waterways. The risks associated with use of triclosan and triclocarban, and identified to date, include: water contamination and resultant harm to fragile aquatic ecosystems; toxicity to algae; bioaccumulation in the fatty tissues of fish; and potential interference with thyroid hormone production (and other endocrine function).

Another cause for concern about the prevalence of triclosan in waterways is that, when exposed to sunlight, it is converted into a dioxin. Dioxins are highly toxic compounds that can cause reproductive and developmental problems, damage immune systems, interfere with hormones, and cause cancer. If that were not sufficiently alarming, triclosan can also combine with chlorine in tap water to form chloroform (which is listed as a probable human carcinogen) — creating yet another toxic exposure.

Water treatment plants do not completely remove triclosan from treated water; thus, it is a contaminant in the “product” of such treatment plants — sewage sludge — which is often spread on land, and even on agricultural land. (One result is that the chemical is now present in earthworms.) Triclosan can bioaccumulate in many organisms and researchers are concerned that it will accumulate and spread through aquatic and terrestrial food webs.

In the face of the slow federal progress on these toxic chemicals in the materials stream, and in personal care products, in particular, Beyond Pesticides offers reminders on nontoxic personal and family hygiene:

- Wash hands frequently and thoroughly. Regular soaps lower the surface tension of water, and thus, wash away unwanted bacteria. Lather hands for at least 10–15 seconds and then rinse off in warm water. It is important to wash hands often, especially when handling food, before eating, after going to the bathroom, and when someone in the household is sick.

- Wash surfaces that come in contact with food with a detergent and water.

- Wash children’s hands and toys regularly to prevent infection.

- If washing with soap and water is not possible, use alcohol-based sanitizers.

In addition, the public can advocate for getting these chemicals out of consumer products by asking the owners or managers of local supermarkets, drugstores, household goods and toy stores, etc., to stop selling products containing them. Beyond Pesticides offers this customizable sample letter to use for such efforts. Local municipalities, schools, government agencies, religious institutions, and businesses are other good “targets” of efforts to persuade such entities to use their buying power to go triclosan-free. See the Beyond Pesticides’ model resolution, which commits the signatory to not procuring or using products containing triclosan.

Source: https://www.beyondpesticides.org/programs/antibacterials/triclosan

A contractor hired through our apartment management used Microban to spray our air ducts. Subsequently, my wife is experiencing respiratory symptoms she likens to Covid-19. While that is exaggerating, I wonder if the Microban has had a deleterious effect on her. Can you comment?

January 4th, 2024 at 6:20 pmHi Craig, thanks for the outreach! Attached is a factsheet on “the ubiquitous triclosan” that includes information on its toxicity and chronic health effects. Triclosan is also listed in our Gateway on Pesticides Hazards here: https://www.beyondpesticides.org/resources/pesticide-gateway?pesticideid=79. For a specific question, please do not hesitate to reach our team at [email protected].

January 16th, 2024 at 12:56 pm