21

Nov

Beekeepers at Risk of Losing Hives after Mosquito Insecticide Spraying

(Beyond Pesticides, November 21, 2018) A study published last month in the Journal of Apicultural Research finds significant numbers of U.S. honey bees at risk after exposure to hazardous synthetic pesticides intended to control mosquitoes. With many beekeepers rarely given warning of insecticide spraying, researchers say the risk of losing colonies could increase. Advocates say fear of Zika and other mosquito-borne illnesses could result in counterproductive and reactionary insecticide spraying that will add further stress to managed and native pollinators already undergoing significant declines.

(Beyond Pesticides, November 21, 2018) A study published last month in the Journal of Apicultural Research finds significant numbers of U.S. honey bees at risk after exposure to hazardous synthetic pesticides intended to control mosquitoes. With many beekeepers rarely given warning of insecticide spraying, researchers say the risk of losing colonies could increase. Advocates say fear of Zika and other mosquito-borne illnesses could result in counterproductive and reactionary insecticide spraying that will add further stress to managed and native pollinators already undergoing significant declines.

Researchers aimed to determine whether neighboring honey bee colonies could be similarly affected by aerial insecticide spraying. To calculate the percentage of colonies that could be affected, density of honey bee colonies by county was compared with projections of conditions thought to be prone to regional Zika virus outbreaks.

Researchers found 13 percent of U.S. beekeepers at risk of losing colonies from Zika spraying. In addition, it was determined that many regions of the U.S. best suited for beekeeping are also those with favorable conditions for Zika-prone mosquitoes to proliferate. These regions include the southeast, the Gulf Coast, and California’s Central Valley.

“[Considering] all the threats facing bees,” says study lead author Lewis Bartlett of the University of Exeter’s Center for Ecology and Conservation in a university press release, “even a small additional problem could become the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

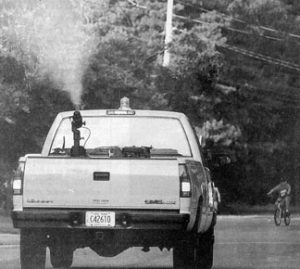

In its 2016 report, Mosquito Control and Pollinator Health: Protecting Pollinators in the Age of Zika and Other Emerging Mosquito Diseases, Beyond Pesticides found, “The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has identified 76 pesticide chemicals that are highly acutely toxic to honey bees. These were singled out because they have an acute contact toxicity value of less than 11 micrograms per bee (LD50<11 micrograms/bee) and can be applied in ways that can expose bees. Of these, several are used to control mosquitoes, including malathion, naled, permethrin and phenothrin, which are the most commonly used for ultra-low volume aerial and ground spraying.” In the report, see Table, Pesticides Used for Mosquito Control, which identifies those mosquito control pesticides that are especially toxic to bees.

Given the scale and uniformity of modern agricultural systems, managed honey bees are increasingly used as supplementary pollinators to service large agricultural areas. Since these pollination services are temporary, farmers must be able to afford an apiarist’s service every year and numerous colony visits per season. With worker-bees already exposed to a range of insecticides while pollinating conventional crops, additional exposure through chemical-intensive mosquito management could cause many farmers to fall into unprecedented financial hardship, as the rental costs of managed-bee colonies increases.

Researchers worry that higher colony density in large agricultural regions demands policies to protect apiaries and the farmers who rely on them. Likewise, advocates say the risk of honey bee colony contamination demands policy makers conduct research to determine effective alternatives to toxic mosquito management methods.

“Many beekeepers live on the breadline,” says Mr. Bartlett, “and if [organophosphate spraying causes] beekeeping [to be] no longer profitable, there will be huge knock-on effects on farming and food prices.”

Entomologists from around the world already classify aerial and ground spraying of insecticides as the least efficient mosquito control technique. Entomologist Dino Martins, PhD, in a 2016 interview with The Guardian, said “We are basically fighting an arms race with mosquitoes rather than cleverly understanding its life cycle and solving the problem there…[R]esistance will always evolve to the use of pesticides….“[Spraying insecticides] is a quick fix but you pay for it. You kill other species that would have predated on the mosquitoes.”

Spraying Naled, the first pesticide recommended by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to combat Zika, has been shown to be ineffective and known to carry consequences. In 2016, over two million bees were killed after aerial mosquito spraying in South Carolina. Beekeepers received insufficient warning for when aerial spraying would occur. One couple reported seeing thousands of dead bees scattered across their pool deck and driveway.

More research is needed to assess the broad ecological harms of mosquito spraying by including poisoning of native pollinators, whose pollination habits sustain a panoply of native plants.

Advocates feel that elected officials’ failure to account for pollinator activity in the decision to spray adds insult to injury. Many advocates wonder how many families could afford the increase in food prices as agricultural pollination costs increase.

With climate change increasing the range for many mosquito-borne diseases, take action locally. Educate your neighbors and community leaders by providing examples of proper mosquito management, such as: eliminating standing water, introducing mosquito-eating fish, encouraging predators like bats, birds, dragonflies and frogs, and using least-toxic larvacides like bacillus thuringiensis israelensis (Bti). Visit Beyond Pesticides’ Mosquito Management page for more information.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Journal of Apicultural Research

no more poison…

November 26th, 2018 at 3:27 pmMosquito treatment is big here in the midwest. I dont think the mosquito companies pay attention to wind speed to battle off target drift We are have a shortage of bees here in Missouri that affect the bee keepers and plant lovers. More sanitation and brush management will help battle the mosquitoes.

November 12th, 2021 at 4:34 pm