11

Jul

High Frequency of Household Pesticide Exposure Can Double the Risk of Parkinson’s Disease Among the General Population

(Beyond Pesticides, July 11, 2023) A study published in Parkinsonism & Related Disorders finds high exposure to household pesticides increases the risk of developing Parkinson’s disease (PD) two-fold. There is a multitude of epidemiologic research on Parkinson’s disease demonstrating several risk factors, including specific genetic mutations and external/environmental triggers (i.e., pesticide use, pollutant exposure, etc.). However, several studies find exposure to chemical toxicants, like pesticides, has neurotoxic effects or exacerbates preexisting chemical damage to the nervous system. Past studies suggest neurological damage from oxidative stress, cell dysfunction, and synapse impairment, among others, can increase the incidence of PD following pesticide exposure. Despite the widespread commercialized use of household pesticides among the general population, few epidemiologic studies examine the influence household pesticides have on the risk of PD, although many studies demonstrate the association between PD onset via occupational (work-related) pesticide exposure patterns.

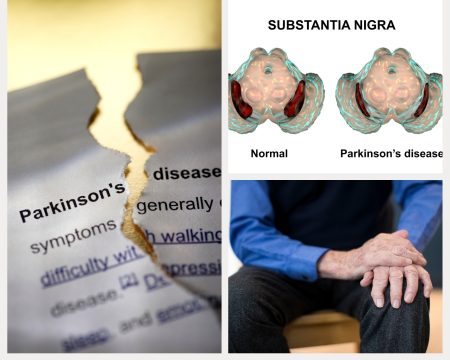

Parkinson’s disease is the second most common neurodegenerative disease, with at least one million Americans living with PD and about 50,000 new diagnoses annually. Alzheimer’s ranks first. The disease affects 50 percent more men than women, and individuals with PD have a variety of symptoms, including loss of muscle control and trembling, anxiety and depression, constipation and urinary difficulties, dementia, and sleep disturbances. Over time, symptoms intensify, but there is no current cure for this fatal disease. While only 10 to 15 percent of PD incidents are genetic, PD is quickly becoming the world’s fastest-growing brain disease. Therefore, research like this highlights the need to examine alternate risk factors for disease development, especially if disease triggers are overwhelmingly nonhereditary.

Using an observational cross-sectional study, the researchers explored the association between household pesticide exposure and PD risk. The researchers selected patients with PD from the Latin American Research Consortium on the Genetics of Parkinson’s Disease (LARGE-PD), and specialists evaluated movement disorders associated with PD. The study extracted data on sex, age at evaluation (for all participants), age at onset for patients with PD, and lifetime smoking history (at least 100 cigarettes during lifetime). To determine household pesticide exposure, researchers asked participants whether they used chemicals to kill various types of pests (e.g., insects, weeds, fungi) in or around the house/apartment during their lifetime (four categories of answers: 1–5 days/year, 6–10 days/year, 11–30 days/year, more than 30 days/year). The study categorizes high exposure to household pesticides as more than 30 days per. Men tend to have higher instances of PD relative to household pesticide exposure. After adjusting for sex, age, smoking, or region of origin, researchers find the risk of PD is independent of these factors, and the odds of developing PD increase two-fold upon from (>30 days/year) household pesticide exposure.

Parkinson’s disease occurs when there is damage to dopaminergic nerve cells (i.e., those activated by or sensitive to dopamine) in the brain responsible for dopamine production, one of the primary neurotransmitters mediating motor function. Although the cause of dopaminergic cell damage remains unknown, evidence suggests that pesticide exposure, especially chronic exposure, may be the culprit. Occupational exposure poses a unique risk, as pesticide exposure is direct via handling and application. A 2017 study finds that occupational use of pesticides (i.e., fungicides, herbicides, or insecticides) increases PD risk by 110 to 211 percent. Even more concerning, some personal protection equipment (PPE) may not adequately protect workers from chemical exposure during application. However, indirect nonoccupational (residential) exposure to pesticides, such as proximity to pesticide-treated areas, can also increase the risk of PD. A Louisiana State University study finds that residents living adjacent to pesticide-treated pasture and forest land by the agriculture and timber industry have higher incidence of PD. Furthermore, pesticide residues in waterways and on produce present an alternate route for residential pesticide exposure to increase the risk for PD via ingestion. In addition to PD, pesticide exposure can cause severe health problems even at low residue levels, including endocrine disruption, cancers, reproductive dysfunction, respiratory problems (e.g., asthma, bronchitis), and other neurological impacts. Nevertheless, direct occupational and indirect nonoccupational pesticide exposure can increase the risk of PD.

This study adds to the research that associates pesticide exposure with PD. A history of high exposure to household pesticides increases the risk of PD regardless of the age at PD onset. Insecticides are the most commonly used household pesticides, particularly synthetic pyrethroids, and organophosphates. Several studies identify various pesticides as involved in the pathology of PD, including the insecticides rotenone and chlorpyrifos and herbicides 2,4-D, glyphosate, and paraquat. A Washington State University study determined that residents living near areas treated with glyphosate—the most widely used herbicides in the U.S.—are one-third more likely to die prematurely from Parkinson’s disease. In the Louisiana State University study, exposure to 2,4-D, chlorpyrifos, and paraquat from pasture land, forestry, or woodland operations, as prominent risk factors for PD, with the highest risk in areas where chemicals quickly percolate into drinking water sources. Overall, research finds exposure to pesticides increases the risk of developing PD from 33 percent to 80 percent, with some pesticides prompting a higher risk than others.

This study adds to the large body of scientific studies strongly implicating pesticide involvement in Parkinson’s disease development. In addition to this research, several studies demonstrate autism, mood disorders (e.g., depression), and degenerative neurological conditions (e.g., ALS, Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s) among aquatic and terrestrial animals, including humans exposed to pesticides. Pesticides themselves, mixtures of chemicals such as Agent Orange (2,4-D and 2,4,5-T) or dioxins, and therapeutic hormones or pharmaceutical products can possess the ability to disrupt neurological function. Therefore, the impacts of pesticides on the nervous system, including the brain, are hazardous, especially for chronically exposed individuals (e.g., farmworkers) or during critical windows of vulnerability and development (e.g., childhood, pregnancy). Considering health officials expect Parkinson’s disease diagnosis to double over the next 20 years, mitigating preventable exposure from disease-inducing pesticides becomes increasingly essential.

Parkinson’s disease has no cure, but preventive practices, like organic agriculture or Parks for a Sustainable Future, can eliminate exposure to toxic PD-inducing pesticides. Organic agriculture represents a safer, healthier approach to crop production that does not necessitate toxic pesticide use. Beyond Pesticides encourages farmers to embrace regenerative, organic practices and consumers to purchase organically grown food. A complement to buying organic is contacting various organic farming organizations to learn more about what you can do. Those affected by pesticide drift can refer to Beyond Pesticides’ webpage on What to Do in a Pesticide Emergency and contact the organization for additional information. Furthermore, see Beyond Pesticides’ Parkinson’s Disease article from the Spring 2008 issue of Pesticides and You.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Parkinsonism & Related Disorders