18

Nov

Research in Traditional Plant Breeding in Organic Tomato Traits Critical to Productivity

(Beyond Pesticides, November 18, 2025) A study published in Horticultural Plant Journal provides additional evidence on the viability of organically managed farmland based on tomatoes cultivated through traditional plant breeding and regional variances.

The authors of the research find that, âDespite the positive trend of the organic sector’s development in Europe, the number of tomato varieties bred for organic farming is still limited since efforts have been mainly focused on high input conditions.â They continue: âAs a result, the existing cultivars may not suit to organic production [ ] as cultivars chosen for conventional [chemical-intensive] systems often respond well to chemical fertilizers to improve crop output, but they might not maximize nutrient uptake in organic systems where minor external inputs are provided.â

In this context, the marketplace is not maximizing the potential productivity of organic systems due to the limited availability of seeds and plant material best suited to conditions in sync with local ecosystems.

The designed methodology, as well as the findings, show that there are opportunities for public investment to support systems that cultivate agricultural products without reliance on petrochemical-based fertilizers, pesticides, and seeds treated with pesticide products and other genetically modified characteristics. For millennia, humans have worked in tandem with native plants and locally or regionally cultivated crop species through plant breeding and cultivation, rather than attempting to control what communities can grow or operate on their land. This latest scientific analysis underscores a path forward that is grounded in science, operates within planetary boundaries, and leads to innovation.

Traditional plant breeding is a process of cross-breeding for selected traits, while genetic engineering actually inserts genetic material into the plant. (See statement of Michael Hansen, PhD., on behalf of Consumers Union.)

Legal Context

Regulations under the Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA) prohibit the use of genetically modified organisms (GMOs) as defined by âexcluded methodsâ in U.S. Department of Agriculture regulations (7 CFR §205.2) and prohibited in 7 CFR §205.105(e).

OFPA itself specifically establishes a default prohibition of âsyntheticâ materials in 7 U.S.C. §6502(22), with a definition that prohibits substances that are (i) not created by ânaturally occurring biological processesâ or (ii) subject to processes that âchemically changesâ a natural material. Allowed and prohibited substances are established in OFPA under the authorities in 7 U.S.C. §6517 (National List) and by statute under the control of the Congressionally mandated National Organic Standards Board (NOSB), a 15-member stakeholder board (7 U.S.C. §6518).

OFPA provides for broad input from the public under the procedures of the NOSB, requiring that, âThe National List established by the Secretary shall be based upon a proposed national list or proposed amendments to the National List developed by the National Organic Standards Board.â For more on engaging with the process to protect and strengthen organic standards, see Keeping Organic Strong.

Background and Methodology

The researchers tested the interaction of environmental and genotypic effects on 21 âmorpho-agronomic traitsâ for 39 distinct tomato genotypes (or accessions, which in this context refers to samples of plant/fruit material representing the selected genotype) grown under certified organic conditions for two years (2019 and 2020) on Italian and Spanish farms. The Italian farm is based in the municipality of Alcasser (ALC), and the Spanish farm is based at the Research Center for Vegetable and Ornamental Crops in Monsampolo del Tronto (MST). The majority of those cultivated tomato types are considered âlandracesâ (local varieties with minimal human plant breeding) or heirlooms (cultivation of landraces from outside the native region), which are found in Italy or Spain; however, seven are heirlooms cultivated in the United States. Chemical traits for each tomato accession were assayed at laboratory facilities in their respective countries (Milan, Italy, and Barcelona, Spain). For further information on the 21 traits and how they are measured, see section 2.2 Phenotyping measurements.

The researchers used a GGE (Genotype plus Genotype by Environment interaction) analysis, rather than the typical analysis of variance (ANOVA) test, because they say, âGGE provides an effective visualization tool to define mean performance and stability of genotypes and to discriminate test environments.â In other words, understanding the impact of genotypic and environmental factors (and their interaction) on crop performance is critical for farmers looking to balance economic competition with ecological regeneration and health.

Using GGE analysis, the researchers identify the highest performing tomato genotypes through assessment of three patterns: âWhich-won-where” (WWW), âmean performance versus stabilityâ (MPvS), and âdiscriminative versus representativeâ (DvR).

Genotypes (genetic characteristics) that fall within the WWW pattern (represented as a polygon on the GGE biplot) are considered the best performing phenotypes (traits) within their respective environments. The genotypes are placed along an axis on the GGE biplot that represents âtheir average performance in all environmentsâ; meanwhile, a âperpendicular line separates genotypes with values below average from those with above average valuesâ. The DvR analysis allowed researchers to assess ideal test environments “where superior genotypes can be effectively selectedâ based on known data from the two locations and two cultivation seasons. For this analysis, the researchers note âthe implementation of the ‘which-won-where’ and ‘mean vs. stability’ models in the GGE analysis facilitated the detection of the most promising cultivars in one or more sites determining furthermore their stability level.â

The researchers are based at the Research Centre for Vegetable and Ornamental Crops and Universitat Politècnica de València. Funding for this project includes grants from the European Unionâs Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program and the Italian Ministry of Agriculture, Food Sovereignty and Forests. In terms of conflicts of interest, âThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.â

Results

In the researchersâ GGE analysis, combining the effects of genotype, location, and seasonal meteorological conditions, the results can be organized based on the three patterns.

In terms of WWW analysis and performance evaluations of specific genotypes:

- âThe accessions âRosada dâAlteaâ (G22) and âEdkawi 1987â (G8) were the best productive during the first season in ALCâ;

- âDuring the second season, âCoeur de Boeufâ (G7) and âRosa de Barbastroâ (G24) were the most yielding accessions in MSTâ;

- âAccession âUco Plataâ (G9) discerned good production and stability during the first season…in ALC and MST, respectively, whereas âAmarillo bombillaâ (G3) and âABC potato leafâ (G34) were seen as least productive accessions across locationsâ;

- ââAmarillo AdemĂşzâ (G19) and âFlor de Baladreâ (G16) were confirmed as the best accessions for fruit weight, ranking second and third, respectively;â and

- âGajo de melonâ (G29) and âMontserratâ (G1) were the accessions with the biggest diameter of the main root displaying values of 2.42 mm and 2.37 mm, respectively.â

In terms of MPvS analysis, the researchers conclude:

- âFor fruit weight, the âmean vs. stabilityâ analysis confirmed âRosada dâAlteaâ (G22), âAmarillo AdemĂşzâ (G19), and âFlor de Baladreâ (G16) as the best performing accessionsâ;

- âOn the contrary, âRosada dâAlteaâ (G22) and âStrogili Megaliâ (G6) were the best performing cultivars with a low projection with respect to the central axis, thus highlighting stability and ranking consistencyâ

- “[T]he graph highlighted 17 out of the 39 tested accessions having a fruit weight above average considering the four environmentsâ; and

- âOverall, 22 out of the 39 tested accessions had a total production above average considering the four environments.â

In terms of DvR analysis to help determine which geographical and meteorological conditions, the researchers conclude:

- âALC 2019 is the ideal environment for the selection of superior genotypes [in terms of fruitweight];

- â[I]t is possible to consider ALC 2020 as a good environment for selecting best candidates in the case of total yield and diameter of the main rootâ; and

- MST 2019 and 2020 were the least discriminating environments in terms of soluble solids content and diameter of the main root. Soluble solids content is important because it contains essential nutrients plants need to thrive, and the diameter of the main root is a helpful indicator that researchers use to assess plant health.

The results of the GGEE analysis of U.S. heirloom genotypes varied, with âBlack cherryâ (G30) considered to have one of the highest stability in terms of the interaction of âgenotypic and environmental factors influencing performance of cropsâ and âGajo de melonâ G29 having the biggest root diameter in the Italian field location and was considered âtop-rankingâ for âsoluble solid content across all environmentsâ; meanwhile ABC Potato leaf (G34) âshowed the genotype to be âlow yieldingâ and âleast productiveâŚacross locations.â

Previous Coverage

Research continues to mount on the economic, public health, ecological, and climate-smart benefits of organically managed cropland, seeds, food products, and agricultural systems.

A Spain-based study published in European Journal of Agronomy finds that âorganic farming equals conventional yield under irrigation and enhances seed quality in drought, aiding food security.â The researchers tested twelve common bean genotypes of Phaselous vulgaris L. âUnder rainfed conditions, the common bean seeds received only minimal water at the beginning of the season to ensure the seedlingsâ survival (Table 1),â say the authors in describing the distinction between the two watering protocols. The study results, when comparing current variable irrigation conditions, conclude that conventional seeds watered through irrigation demonstrate the highest yields and caloric value; however, organic seeds under rainfed conditions promote protein, fiber, and nitrogen fixation. The authors note that the choice of variety (genotype) matters more in organic seeds for efficient use of sunlight through photosynthesis (the underlying biological mechanism that contributes to yield results in plants), suggesting that breeding could potentially offset any category of disadvantage that organic systems may have. (See Daily News here.)

Meanwhile, a Kenya-based study published in European Journal of Agronomy, based on a 16-year, long-term experiment (LTE), finds that organic crops (cotton production with wheat and soybean rotations) in tropical climates are competitive with chemical-intensive (conventional) systems when evaluating systemsâ resilience (to weather and insect resistance), input costs, and profitability. (See Daily News here.) This study is an extension of the Rodale Instituteâs Farming System Trial (FST), a 40-year-long field study published in 2020 with the overarching goal of â[a]ddress[ing] the barriers to the adoption of organic farming by farmers across the country.â (See Daily News here.) The FST finds:

- Organic systems achieve 3â6 times the profit of conventional production;

- Yields for the organic approach are competitive with those of conventional systems (after a five-year transition period);

- Organic yields during stressful drought periods are 40% higher than conventional yields;

- Organic systems leach no toxic compounds into nearby waterways (unlike pesticide-intensive conventional farming);

- Organic systems use 45% less energy than conventional systems; and

- Organic systems emit 40% less carbon into the atmosphere.

Building on the climate-smart benefits of organic agriculture documented in recent scientific literature, a comprehensive U.S.-based study released in Journal of Cleaner Production in August 2023 identifies the potential for organic farming to mitigate the impacts of agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the fight to address the climate crisis. In âThe spatial distribution of agricultural emissions in the United States: The role of organic farming in mitigating climate change,â the authors determine that âa one percent increase in total farmland results in a 0.13 percent increase in GHG emissions, while a one percent increase in organic cropland and pasture leads to a decrease in emissions by about 0.06 percent and 0.007 percent, respectively.â (See Daily News here.)

You can learn more here about the biodiversity and public health risks of reliance on genetic engineering to address pest management concerns.

Call to Action

Taking action is as easy as a few clicks. See the Action of the Week archive here and sign up now to get our Action of the Week and Weekly News Updates delivered right to your inbox. One of the most recent actions you can take  (see here) is telling your Congressional Representative and Senators to cosponsor and support the Organic Science and Research Investment Act (OSRI), which would double investments in organic research and land management practices.

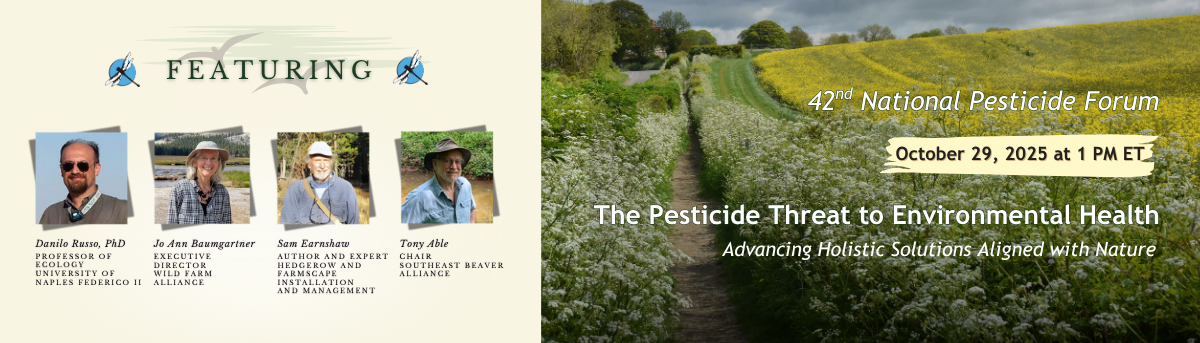

To advance principles of land management that align with nature, see the recording of Beyond Pesticides 42nd National Forum, The Pesticide Threat to Environmental Health: Advancing Holistic Solutions Aligned with Nature, which brings together scientists and land managers working to recognize and respect the ecosystems on which life depends. The second session is scheduled for December 4, 2025, 1:00-3:30 pm (Eastern time, US). This session features Carolina Panis, PhD, Jabeen Taiba, PhD, and Emile Habimana, M.S., in a compelling discussion that elevates public understanding of the scientific data linking petrochemical pesticides to the crisis in breast cancer, pediatric cancer, and sewage sludge (biosolids) fertilizerâsupporting the imperative for ecological land management.

The virtual Forum is free to all participants. See featured speakers! Â Register here.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Horticultural Plant Journal

![Image credit: [Mahmut yilmaz from Pexels] via Canva.com](https://beyondpesticides.org/dailynewsblog/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/DN-11.6.25-1.jpg) âAt one point, he was a pesticide applicator and I specifically remember he would wear white jumpsuits, at the time he was probably around 30 years old. We knew he worked with chemicals that could be unsafe to us and he took precautions to make sure we didnât come in contact with the chemicals. I knew that we couldnât hug him when he picked us up after work, he never wore his jumpsuit in the home and would leave it outside the house. We also washed our clothes separately. My dad started showing symptoms of Parkinsonâs disease over several years, starting with his nervous system. It started with his nerves and trembling hands and then he began to stutter. We started taking him to the doctor and he was eventually diagnosed with Parkinsonâs disease. I donât remember for how long he had symptoms before he was diagnosed but I do remember how hard it was for my dad.â

âAt one point, he was a pesticide applicator and I specifically remember he would wear white jumpsuits, at the time he was probably around 30 years old. We knew he worked with chemicals that could be unsafe to us and he took precautions to make sure we didnât come in contact with the chemicals. I knew that we couldnât hug him when he picked us up after work, he never wore his jumpsuit in the home and would leave it outside the house. We also washed our clothes separately. My dad started showing symptoms of Parkinsonâs disease over several years, starting with his nervous system. It started with his nerves and trembling hands and then he began to stutter. We started taking him to the doctor and he was eventually diagnosed with Parkinsonâs disease. I donât remember for how long he had symptoms before he was diagnosed but I do remember how hard it was for my dad.â