15

Aug

(Beyond Pesticides, August 15, 2025) In analyzing the data present in an article in Data in Brief, concerning levels of pesticide biomarkers are present in the urine of adolescents and young adults that are linked to numerous health implications. The biomonitoring data, collected at two time points from participants in a longitudinal cohort study in the agricultural county of Pedro Moncayo, Ecuador, encompasses a total of 23 compounds used as herbicides, insecticides, and fungicides and their associated metabolites (breakdown products), which include organophosphates, pyrethroids, and neonicotinoids. The results highlight the disproportionate risks to a Latin American population that occur as a result of living in areas with heavy chemical-intensive agriculture.

âThis article presents urinary pesticide metabolite concentrations for 665 participants in the âStudy of Secondary Exposure to Pesticides among Children, Adolescents, and Adultsâ (ESPINA), which were collected during two follow-up assessments,â the authors describe. The first sampling period from July to October 2016, referred to as Follow-up Year [FUY]-8b, includes 529 of the participants, while the second sampling period from July to September 2022 (FUY-14a) includes 505 of the participants. All participants are within the agricultural community of Pedro Moncayo.

As the authors note, âThe ESPINA study aimed to include a balanced mix of children who did and did not cohabitate with a floricultural or agricultural worker.â This highlights both the exposure routes from the surrounding environment as well as indirect occupational exposure from another occupant in the house through contaminated clothing and items.

The use of biomonitoring data in relation to pesticide exposure, particularly in agricultural communities, shows real-world exposure as well as the heightened health risks to farmworkers, their families, and individuals living near agricultural land. âUnlike self-reported data or environmental sampling, biomonitoring provides objective, quantitative evidence of exposure, capturing multiple pathways such as inhalation, ingestion, and dermal absorption,â the researchers state.

These pathways offer insight into acute, chronic, and low-dose exposure that studies connect to long-term adverse health effects. With this study focused on Latin America, where agricultural work is prevalent and supports many individuals and families, biomonitoring data is valuable in understanding the impacts of chemical exposure.

The ESPINA cohort was initially established in 2008 with a goal âto investigate the impacts of pesticide exposure on development from childhood to adulthood in individuals living within the agricultural community of Pedro Moncayo, Pichincha, Ecuador.â With cut flowers as one of the primary exports from Ecuador, and an emphasis in Pedro Moncayo on rose and flower cultivation, data from this region incorporates exposure to a variety of pesticides from multiple chemical classes.

âOf the 505 participants examined in 2022 (FUY-14), 212 were returning participants who had been examined in 2016, while the remaining 293 were newly recruited at that timepoint,â the researchers note. They continue, âAcross both 2016 and 2022, a total of 665 distinct individuals contributed to the dataset, with 212 individuals contributing data at both timepoints and the remaining participants providing data at only one of the two examination periods.â

To assess the levels of biomarkers for specific pesticide metabolites, urine samples were collected from participants in 2016 and 2022 upon awakening, considered a first morning void, and analyzed through chromatography and spectrometry techniques. (See additional Beyond Pesticides coverage of biomonitoring studies using urine samples in agricultural communities here, in newborns and children here and here, and from nonoccupational exposure here.)

For the 2016 examination (FUY-8b), 19 metabolites are screened for that correlate with 21 total compounds. The second examination in 2022 (FUY-14a) screens for 14 metabolites that correlate with 20 total compounds, overlapping with 18 compounds from the first sampling period.

In FUY-8b, biomarkers included are associated with the following pesticides:

- Organophosphates (parathion, chlorpyrifos, diazinon, malathion)

- Pyrethroids (cyhalothrin, cypermethrin, deltamethrin, fenpropathrin, permethrin, tralomethrin, cyfluthrin, flumethrin)

- Neonicotinoid Insecticides (imidacloprid, acetamiprid, clothianidin, thiamethoxam, thiacloprid)

- Herbicides (glyphosate, 2,4-D)

- Fungicides (ethylene bis-dithiocarbamates (EBDC) such as maneb and mancozeb)

- Insect Repellent (N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET))

The FUY-14a screening includes all of the above except for thiacloprid, glyphosate, and EBDC and has the addition of two systemic insecticides, sulfoxaflor (a sulfoxamine) and flupyradifurone (a butenolide).

The results show the FUY-14a participants have higher urinary pesticide biomarker concentrations for seven biomarkers that are associated with parathion, chlorpyrifos, cyhalothrin, cypermethrin, deltamethrin, fenpropathrin, permethrin, tralomethrin, cyfluthrin, imidacloprid, acetamiprid, clothianidin, and thiamethoxam but lower for 2,4-D, malathion, and DEET in comparison to the concentrations from the earlier FUY-8b screening. Â

Metabolite concentrations with detection rates of 30% and above are noted for 11 out of 19 metabolites measured in 2016 and 12 out of 16 metabolites measured in 2022. The metabolites at the lower detection rates correlate with only seven of the above-listed parent chemicals in the 2016 screening and four from the 2022 screening. In both sampling periods, two organophosphate pesticide metabolites, which are associated with chlorpyrifos and parathion, have a 100% detection rate. These results highlight the widespread exposure to pesticides that the individuals living and working in agricultural communities experience.

For all of the compounds that are detected above 30%, the Gateway on Pesticide Hazards and Safe Pest Management links them to a multitude of health and environmental implications including cancer, endocrine disruption, reproductive effects, neurotoxicity, kidney/liver damage, birth/developmental effects, and toxicity to birds, bees, and aquatic organisms, among others.Â

As the authors of the current study point out: âOne major limitation of measuring pesticide metabolites in urine using mass spectrometry is the short half-life of metabolites, which leads to a narrow window of exposure. Since pesticides are often rapidly metabolized and excreted, a single urine sample may not accurately reflect long-term exposure.â Additional biomonitoring studies for pesticide residues analyze breast milk, sperm, hair, nails, and blood.

In a recent study comparing pesticide concentrations in conventional and organic farmers, hair and nails are used for biological samples, which reflect cumulative exposure, unlike blood or urine, which only account for recent exposure. As the study authors point out, âHair sequesters trace elements over weeks, while nails, due to their slower growth rate, reflect exposure over several months.â (See Daily News coverage here.) Additional sampling of the hair of over 200 French children finds 69 biomarkers of pollutants and pesticidesâ12 of which are bannedâthat highlight heightened risks of early childhood exposure in combination with prenatal exposure from their mothers. (See additional analysis of the study here.)

Biomonitoring studies not only inform disproportionate risks and the widespread pesticide contamination that contributes to body burden, but they also offer insight into how organic systems can eliminate direct and indirect exposure to these toxicants and reduce the levels of pesticide residues in the body even in short amounts of time.

A 2024 literature review, published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, explores levels of pesticide residues found in samples of human urine with environmental exposure and dietary intake and confirms prior findings about the benefits of an organic diet. Similar to past findings, lower concentrations of chemicals are detected in the urine of participants who report eating an organic diet. (See Daily News here.)

Another study in 2025, from a randomized clinical trial published in Nutrire, finds that adopting a fully organic diet can reduce pesticide levels in urine within just two weeks by an average of 98.6% and facilitates faster DNA damage repair relative to a diet of food grown with chemical-intensive practices. The authors explain that their finding âis likely due to two main factors: the presence of compounds characteristic of [an organic] diet, which may have high levels of antioxidants that can protect DNA and also induce DNA repair [], and the absence or decrease in the incidence of pesticides in this type of diet, which are recognized for their genotoxic effects and have the ability to affect the genetic repair system of organisms [].â (See Daily News here.)

Learn more about the health effects of pesticide exposure in the Pesticide-Induced Diseases Database, as well as the health and environmental benefits of organic agriculture and land management here and here.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source:

Parajuli, R. et al. (2025) Urinary pesticide biomarkers from adolescence to young adulthood in an agricultural setting in Ecuador: Study of secondary exposure to pesticides among children, adolescents, and adults (ESPINA) 2016 and 2022 examination data, Data in Brief. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2352340925006067.

Posted in 2,4-D, acetamiprid, Agriculture, Biomonitoring, Children, Chlorpyrifos, Clothianidin, Cyfluthrin, cypermethrin, DEET, Deltamethrin, Diazinon, fenpropathrin, Flumethrin, flupyradifurone, Glyphosate, Imidacloprid, International, lambda-cyhalothrin, Malathion, mancozeb, Maneb, Metabolites, neonicotinoids, Occupational Health, organophosphate, Parathion, Permethrin, pyrethroids, Repellent, Sulfoxaflor, Synthetic Pyrethroid, Synthetic Pyrethroids, thiacloprid, Thiamethoxam, tralomethrin by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

14

Aug

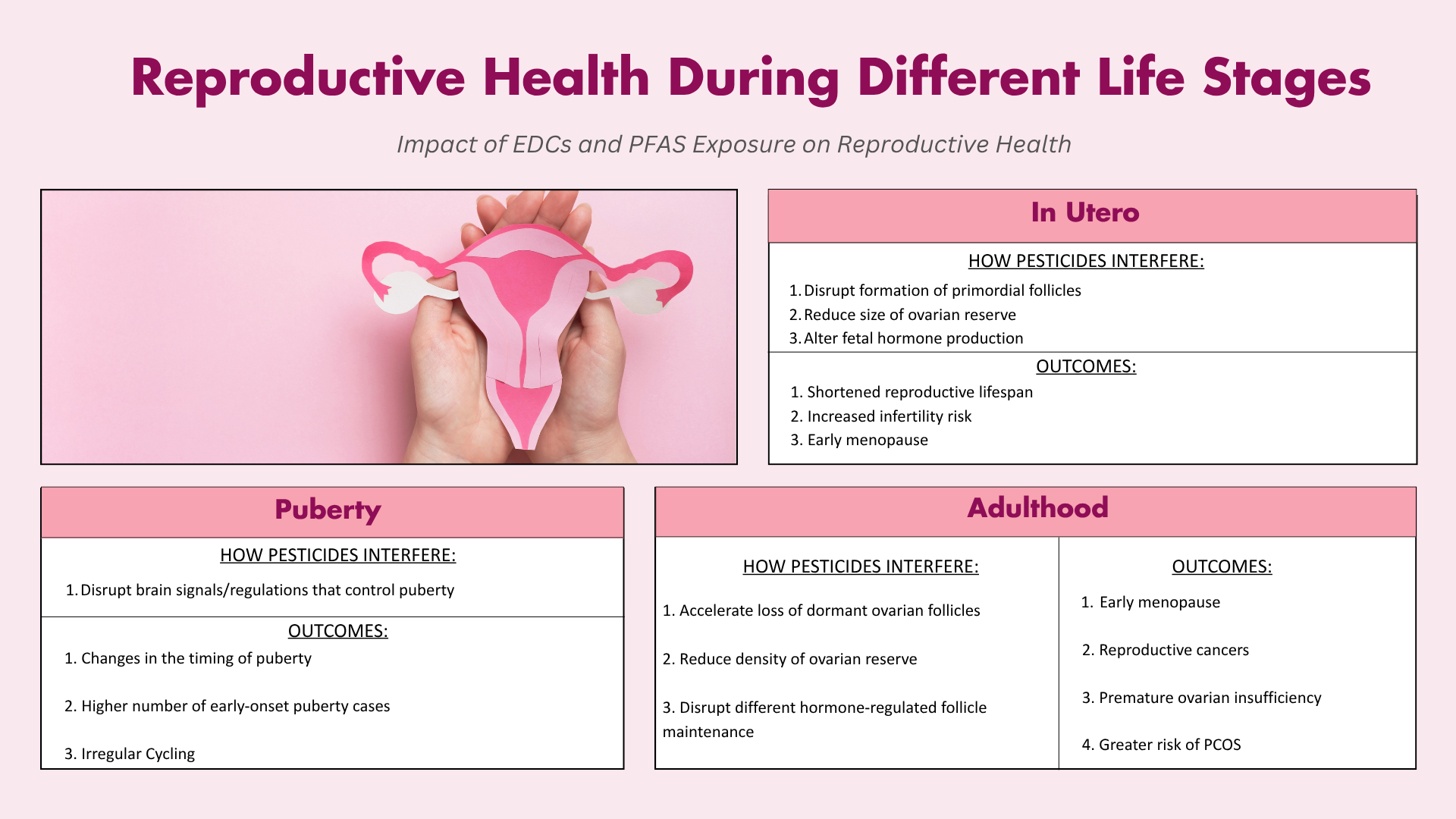

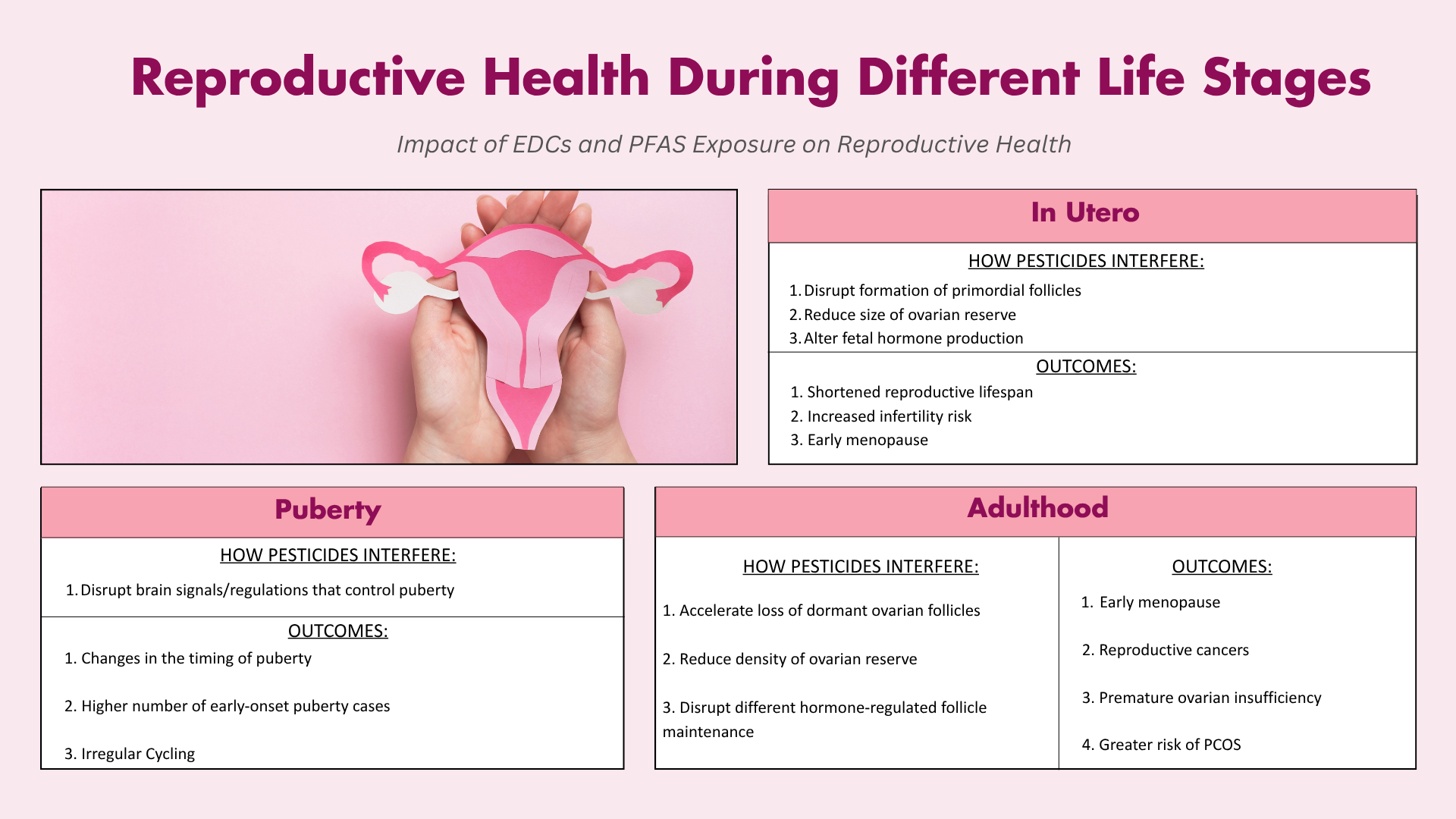

(Beyond Pesticides, August 14, 2025) A review in Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology links various classes of environmental pollutants including pesticides and per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), both of which Beyond Pesticides has extensively covered, to adverse effects on the female reproductive system and common mechanisms of toxicity. These chemicals âdisrupt the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis (HPG), impair ovarian function, and contribute to reproductive dysfunction through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, hormonal disruption, and epigenetic [gene expression or behavior] modifications,â the authors say. This leads to menstrual irregularities, infertility, and pregnancy complications, as well as increases in the risk of reproductive system disorders such as endometriosis, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), and ovarian cancer, among others.

âAdditionally, transgenerational effects mediated by epigenetic modifications, germ cell damage, and placental transfer may adversely affect offspring health, increasing the risk of reproductive dysfunction, neurodevelopmental disorders, metabolic diseases, and cancer,â the researchers explain. This study, integrating recent epidemiological and experimental findings, provides an overview of major chemical classes that threaten womenâs health and highlights the need for immediate action.

As the authors point out, female reproductive health is important not only for those who choose to plan for a family but also for the overall well-being and general health of women. Hormonal balance, immune regulation, and the proper functioning of the HPG axis are crucial in impacting other aspects of health aside from reproduction. A wide body of scientific literature finds that environmental chemicals disrupt the sensitive equilibrium of hormones within the body, as well as impair reproductive processes and contribute to long-term health outcomes. (See the Pesticide-Induced Diseases Database.)

However, many data and knowledge gaps still exist. âReal-world exposure typically involves long-term, low-level exposure to complex mixtures, yet most research focuses on the high-dose effects of individual chemicals,â the researchers note. They continue, âAdditionally, the transgenerational [across multiple generations] effects of chemical exposure, particularly how maternal exposure may influence health and fertility in subsequent generations, are still not fully understood.â

Literature Review of Multiple Chemical Classes

The authors analyze studies that link exposure to environmental contaminants with adverse effects to womenâs reproductive health. The chemical classes within the review include plasticizers, PFAS, heavy metals, pesticides, organophosphate flame retardants (OPFRs), polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), volatile organic compounds (VOCs), microplastics, quaternary ammonium compounds (QACs), and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), many of which are related to chemical-intensive land management and can exacerbate health effects through additive or synergistic effects, like microplastics when in contact with petrochemical pesticides and synthetic fertilizers. Â

PFAS

As explained in previous Daily News, the multitude of sources of PFAS and various exposure routes lead to widespread contamination of the environment and organisms. PFAS in agriculture represents a large source of exposure, as the chemicals can be pesticide active ingredients, used in the plastic containers pesticides are stored in, and as surfactants in pesticide products. Additionally, PFAS are used in many other plastic storage containers and food packaging, personal care products, nonstick cookware, cleaning supplies, treated clothing, firefighting foam, and machinery and equipment used in manufacturingâall of which contaminate food, water, soil, and the air.Â

In the current literature review, the researchers share evidence of the link between PFAS exposure and adverse pregnancy outcomes, including hypertensive disorders such as preeclampsia, miscarriage, fetal growth restriction, low birth weight, and premature birth. âSuch exposure can disrupt hormone signaling pathways by mimicking or blocking natural hormones, leading to impaired follicular development, reduced oocyte quality, and disrupted ovulation,â the authors state. âThis hormonal imbalance may result in irregular menstrual cycles, amenorrhea [absence of menstruation], and overall decreased fertility.â (See studies here, here, and here, as well as additional studies on birth/fetal effects in the Pesticide-Induced Diseases Database.)

Pesticides

Research shows that pesticides induce oxidative stress, which leads to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage reproductive tissues. This can impact both males and females by impairing ovarian and testicular function, disrupting oocyte (a developing egg cell in the ovaries) maturation, and reducing sperm quality.

Study results highlighted in the review include:

- Organophosphates cause imbalances in sex hormone levels. (See here.) This can result in âreduced libido, altered menstrual cycles, ovarian dysfunction, and impaired spermatogenesis, ultimately decreasing fertility in both men and women.â

- Glyphosate and organochlorines are linked to DNA strand breaks, chromosomal abnormalities, and the formation of abnormal nuclear structures in reproductive cells. (See research here.)

- âPesticides primarily affect human reproduction by functioning as endocrine disruptors, by either enhancing or inhibiting the effects of natural hormones. Additionally, they can induce oxidative stress, leading to cellular damage, metabolic disturbances, and cell death.â (See study here and recent Daily News coverage here.)

- Women exposed to pesticides experience âreduced fertility, increased risk of miscarriages, babies born prematurely or with low birth weight, developmental issues, ovarian dysfunction, and disruption of hormonal regulatory pathways.â (See studies here and here, as well as additional Daily News coverage on negative birth outcomes here.)

- Pesticide toxicity can additionally cause adverse pregnancy outcomes by disrupting placental function.

Mechanisms of Reproductive Toxicity

Exposure to toxic chemicals can result in negative impacts on the ovaries, uterus, fallopian tubes, and hormonal regulation, among others. Since the female reproductive system is tightly regulated by hormones, any imbalance can lead to damaged cells and disrupted biological processes that are crucial for reproduction and development. Environmental contaminants can âimpair oocyte multiplication, growth, and maturation through mechanisms such as oxidative stress, endocrine disruption, and DNA damage,â the researchers note. With many pesticides acting as endocrine disruptors, they can also influence cells within the ovaries and prevent processes, such as folliculogenesis and steroidogenesis, from properly occurring. (See research here and here.)

One study finds that neonicotinoid exposure, through the mechanisms of oxidative stress and DNA damage, leads to apoptosis (programmed cell death) and necrosis (uncontrolled cell and tissue death). Additional studies show PFAS exposure can harm uterine immunity, increasing the risk of endometrial disorders like endometriosis and uterine leiomyoma, as well as reduce ovarian reserve and disrupt menstrual cycles by interfering with hormone synthesis.

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs), including pesticides, can impact the functioning of the HPG axis, which is âessential for regulating reproductive functions, including follicular growth, ovulation, spermatogenesis, and hormone production,â the authors note. Since EDCs mimic sex hormones, they disrupt homeostasis within the HPG axis, âleading to impaired folliculogenesis, ovulation, conception, spermatogenesis, and fertility.â (See study here.)

Transgenerational Effects

As the review emphasizes: âEnvironmental chemicals affect not only exposed individuals but also future generations through mechanisms such as epigenetic modifications, germ-cell damage, and placental transfer. Pollutants like PFAS, heavy metals, pesticides, microplastics, and QACs have been linked to adverse effects on offspring, including impaired reproductive, neurological, metabolic, and immune health, as well as increased cancer risk.â This occurs through induced epigenetic changes, defined as altered gene expression without changing DNA sequences. (See Daily News Multitude of Studies Find Epigenetic Effects from PFAS and Other Endocrine Disrupting Pesticides.) These alterations can be passed down through multiple generations and further impact health and development.

Chemical exposure can âdirectly damage DNA in oocytes and sperm, causing mutations or chromosomal abnormalities that are passed to offspring… [and] significantly impairs offspring reproductive health, including reduced ovarian reserve, disrupted follicular development, altered oviduct morphology and function, and poor sperm quality.â Studies also reveal that PFAS and pesticide exposure during pregnancy is linked to increased attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnoses in children. (See studies here and here and relevant Daily News coverage here.)

Transgenerational exposure is also associated with a heightened risk of hormone-related cancers, such as breast and testicular cancer. Maternal PFAS exposure âhas been implicated in an elevated risk of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) and chromosomal abnormalities.â The authors continue, âSimilarly, maternal exposure to EDCsâsuch as PCB, pesticides, benzene, and DDTâduring fetal development is consistently associated with a higher risk of testicular cancer, particularly nonseminomas, in male offspring.â (See study here.)

The direct link to adverse reproductive effects in individuals exposed to environmental contaminants like pesticides and PFAS, as well as the subsequent effects on their offspring, requires systemic change. As the researchers advocate, âTaking proactive measures now is critical for ensuring the health and well-being of future generations.â

Organic Solution

Eliminating the use of harmful chemicals is at the forefront of Beyond Pesticidesâ mission. Through the widespread adoption of organic agriculture and land management, Beyond Pesticides seeks to protect healthy air, water, land, and food for ourselves and future generations by removing the chemicals that pose unreasonable risks to life.

Learn more about how pesticide exposure impacts womenâs reproductive health on Beyond Pesticidesâ newly published Reproductive Health Effects page, as well as the health and environmental benefits of organic here and here.

📣 Tell Congress to insist on eliminating pesticides that endanger women’s health.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source:

Xie, Y., Peng, R. and Xiao, L. (2025) Environmental Chemicals and Female Reproductive Health: Unraveling Mechanisms and Societal Impacts â A Narrative Review, Clinical and Experimental Obstetrics & Gynecology. Available at: https://www.imrpress.com/journal/CEOG/52/8/10.31083/CEOG39882/htm.

Posted in Birth defects, Cancer, contamination, Developmental Disorders, DNA Damage, Endocrine Disruption, Epigenetic, Glyphosate, Infertility, Miscarriage, multi-generational effects, organochlorines, organophosphate, Oxidative Stress, PCOS, Reproductive Health, synergistic effects, Women's Health by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

13

Aug

(Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2025) The data on the adverse effects of the insecticide chlorpyrifos, still widely used in food production, continued to accumulate with the latest being a study published in PLOS One that finds perinatal exposure to the chemical in mice can alter sleeping patterns, lead to brain inflammation (particularly in female individuals), and impact gene expression linked to immune response and epigenetic effects. The adverse health effects are greater overall in female mice than male mice, emphasizing the significance of disproportionate impacts across species.

Chlorpyrifos has been a threat to human and ecological health for decades, originally as a general-use pesticide for homes, gardens, and agriculture, and then restricted to most nonresidential uses in 2000. Currently, the chemicalâs permitted uses include food and feed crops, golf courses, as a non-structural wood treatment, and adult mosquito control for public health (insect-borne diseases) uses only. According to health and environmental advocates, there is a long history of U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) failure to adequately protect human and environmental health from chlorpyrifos, which is linked to endocrine disruption, reproductive effects, neurotoxicity, brain, kidney, and liver damage, and birth and developmental effects.

It took 21 years after negotiating a stop to most residential uses for EPA to negotiate a ban of the agricultural uses of chlorpyrifos in 2021 after a U.S. Court of Appeals found its registration to be flawed; then, that court decision was vacated by a 2023 Appeals Court decision (see also Daily News), sending EPA back to its pre-2021 allowed agricultural uses. In December 2024, EPA issued a proposed rule to restrict chlorpyrifosâ allowance to 11 major crops, which are among the most extensively grown and used in the U.S.: soybeans, sugar beets, cotton, wheat, apples, citrus fruits, strawberries, alfalfa, cherries, peaches, and asparagus. The public comment period closed in February 2025. (See Beyond Pesticidesâ commentary on some of chlorpyrifosâ history.)

In addition to the adverse human health effects, chlorpyrifos is also known to be toxic to birds, bees, fish, and other aquatic organisms and is detectable in groundwater. Advocates continue to call for a more transformational approach rather than focusing on whack-a-mole tactics that focus on the harm of one pesticide after pesticide, rather than advocating for alternative agricultural and land management systems that render their perceived utility moot.

Background and Methodology

In the study, the test subjects are âwild-type C57BL/6â mice (a common strain of laboratory mouse species) in a controlled environment kept at 23-25 degrees Celsius (roughly 73 to 77 degrees Fahrenheit) on a 12-hour light-dark cycle. Mice are fed âad libitum,â or as they desire. Mice were split up into groups exposed to chlorpyrifos via oral gavage in peanut oil and a control group. The exposure window was from mating until weaning, with mouse offspring (âpupsâ) not directly exposed to the pesticide to home in on perinatal exposure.

The main hypothesis of this study was to determine if perinatal exposure to chlorpyrifos, during pregnancy and lactation periods, causes long-lasting disruptions in sleep-related breathing and promotes neuroinflammation for subjects moving into adulthood, possibly in a sex-specific manner. The researchers based their hypothesis on prior evidence of the insecticide crossing the placental barrier and showing up in breast milk, as well as links to adverse effects on neurodevelopment and respiration in humans and non-humans.

The experimental procedures to test for perinatal health include confirmation that the offspring were properly exposed to chlorpyrifos by assessing acetylcholinesterase (AChE) (enzyme necessary to nervous system transmission) activity, various behavioral tests (pre-birth surgery), surgical implantation of electrodes to assess brain activity and muscle movement, sleep and breathing recordings, blood test to assess stress via corticosterone levels, and oesterous cycle monitoring to assess behavioral and brain activity for female mice. After all the tests, the mice were euthanized and hippocampi collected to measure inflammation, anti-inflammatory regulation, stress response, and epigenetics. The researchers leveraged various statistical analysis tools to account for these various biological indicators, which can be found in more detail on pages three to seven of the study.

The researchers for this study are all experts at the University of Bologna in various specialties, including the Department of Pharmacy and Biotechnology, the Department of Biomedical and Neuromotor Sciences, the Department of Medical and Surgical Sciences, the Center for Applied Biomedical Research, and PRISM Lab. This study was approved by both the Universityâs Committee on the Ethics of Animal Experiments and the Italian Ministry of Health, following guidelines laid down by the Committee and ARRIVE (Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiments) guidelines.

Results

The authors were able to prove their hypothesis that chlorpyrifos exposure leads to adverse health effects in mice, particularly on sleep, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental harms and disruptions. The six main categories of findings include:

- Mother mice treated with the pesticide had significantly reduced AChE activity, confirming that Chlorpyrifos was present during pregnancy and breastfeeding of offspring mice.

- Adult mice with perinatal Chlorpyrifos exposure faced more apneas and more sighs, with apneas occurring during both light and deep sleep cycles.

- The hippocampus of female mice showed higher levels of inflammatory genes and lower levels of their anti-inflammatory counterparts, suggesting chronic brain inflammation.

- Enzymes involved with regulating inflammation (histone demethylases) were significantly reduced in female mice

- Male mice exposed to the insecticide showed an increased expression of Nr3c1 (glucocorticoid receptor), which could signal an altered stress response regulation.

- Chlorpyrifos-exposed mice were described as having mixed results in terms of other cognitive and behavioral findings, including potential indicators for improved working memory or hyperactivity.

Previous Research and Actions

The scientific literature demonstrates that toxins like microplastics, heavy metals, synthetic fertilizers, per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), and pesticides (including whole formulations, active ingredients, âinerts”, synergists, pesticide-treated seeds, and plant growth regulators) have synergistic effects that threaten biodiversity, including aquatic organisms. This means the combined toxicity of the two (or multiple) substances is greater than the sum of the two individual exposures. The most recent study to demonstrate this, published in Ecotoxicology, focuses on the impacts of microplastics and chlorpyrifos on cladocerans, a group of microcrustaceans. There was no mortality observed in microplastic-only treatments, while microplastics preconditioned with the insecticide showed acute effects. Chronic exposure also shows reduced survival and reproductive output in both species. The researchers state: âA significant delay in age at first reproduction and shorter generation time were observed in the presence of MP^CPF, suggesting MP-mediated enhanced toxicity of CPF, wherein CPF could have accumulated onto the MP surface, thus, intensifying its toxicity.â (See Daily News here.) Researchers developed a novel tool in a study published in Nature Communications this year that successfully creates a map of the âpesticide-gut microbiota-metabolite network,â identifying âsignificant alterations in gut bacteria metabolism. Chlorpyrifos was one of eighteen pesticide compounds showing significant potential metabolic shifts in the gut microbiome. (See Daily News here.)

There has been a somewhat global shift in recognizing the toxicity of chlorpyrifos. The United Nationsâ Conference of Parties (COP) for the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs), originally adopted by 128 countries in 2001, voted to move chlorpyrifos, a neurotoxicant linked to brain damage in children, to Annex A (Elimination) with exemptions on a range of crops, control for ticks for cattle, and wood preservation, according to the POPs Review Committee. (See Daily News here.)

In terms of recent legal history on the organophosphate insecticide, a three-judge panel of the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in May 2021 instructed EPA to either revoke the tolerances the agency had set for chlorpyrifosâs residue in various foods or demonstrate that they meet the statutory and regulatory standards. Finally, after 21 years of delay, EPA issued a final rule in August 2021 revoking all food tolerances for the chemical. This seemed to signal a step in the right direction after relentless grassroots advocacy and judicial oversight prompted regulatory action until February 2022, when a different set of petitionersâpesticide corporations, groups representing industrial agriculture, and other countriesâ agricultural interests vested in fossil fuel-dependent food systemsâfiled an action in the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals. In November 2023, a three-judge panel of the Eighth Circuit reversed EPAâs momentous 2021 decision, rendering the Ninth Circuitâs opinion moot. (See additional Daily News coverage and additional commentary on the saga of chlorpyrifos litigation and regulations here, here, here, and here.)

Call to Action

Beyond Pesticides submitted comments (see here) earlier this year on a Federal Register notice to âto revoke all tolerances for residues of chlorpyrifos, except for those associated with the use of chlorpyrifos on the following crops: alfalfa, apple, asparagus, tart cherry, citrus, cotton, peach, soybean, strawberry, sugar beet, and spring and winter wheat.â Beyond Pesticides, citing alternatives and the clear weight of evidence on neurological and a suite of health impacts, called for the total cancellation of chlorpyrifos use. This builds on decades of previous advocacy in offering comments rooted in the latest scientific evidence and findings, as you can see in the pesticideâs entry in the Gateway on Pesticide Hazards and Safe Pest Management.

Consider taking action today by subscribing to Action of the Week and Weekly News Update, and stay updated on the latest studies, analysis, whatâs going on in Congress, and other developments that impact your community!

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: PLOS One

Posted in Brain Effects, Chlorpyrifos, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Epigenetic, Immunotoxicity, Litigation, Sleep Disorders, Uncategorized by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

12

Aug

(Beyond Pesticides, August 12, 2025) Last week on August 9, the United Nations observed International Day of the Worldâs Indigenous Peoples, a critical acknowledgement of Indigenous âfood sovereignty, food security, biodiversity conservation and climate resilience,â as outlined in the report of the Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, Eighteenth Session (July 14â18, 2025).

As the report states, under Article 20 of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, âIndigenous Peoples possess distinct economic systems rooted in traditional knowledge, practices and resources and have the right to sustain, strengthen and develop these systems in accordance with their cultures, traditions, values and aspirations.â It continues, âWhen deprived of their means of subsistence and development, this article provides that Indigenous Peoples are entitled to just and fair redress.â In a statement recognizing the importance of the day, Special Rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous Peoples, Albert K. Barume, focuses on the need for Artificial Intelligence (AI) to recognize that, âIndigenous Peoples have long been stewards of knowledge, biodiversity, and sustainable living [and] [w]ithout their meaningful participation, AI systems risk perpetuating historical injustices and deepening the violation of their rights.â

Meanwhile, the current U.S. administration has shifted away from federal policies and is dismantling programs, including the termination of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agencyâs (EPA) Environmental Justice program, intended to address disproportionate harm associated with chemical exposure among Native Americans and people of color communities. (See EPA Launches Biggest Deregulatory Action in U.S. History.)

Indigenous communities lead the charge in biodiversity protections and pollinator well-being, having thrived and lived in coexistence with nature long before the industrialized food systems and systemic separation from, and poisoning of, the land. The organic movement of the post-World War II era emerged with individual farmers selling pesticide-free produce to interested community members, eventually coming together to form networks with other like-minded environmental justice and public health advocates in the 1970s and 1980s to form voluntary organic standards that eliminate the need for toxic agricultural chemicals while creating a new, vibrant, organic economic sector. With the U.S. organic sector valued at $71.6 billion in 2024, according to the Organic Trade Association, advocates must recognize the leadership of Indigenous sovereignty and stewardship in laying the foundation for organic criteria and principles rooted in a precautionary principle that prioritizes nature, health, and sustainability before profits.

Recent Developments

Indigenous people around the world are playing a leadership role in challenging disproportionate harm from chemical exposure patterns associated with chemical-intensive agriculture.

Exposure in agricultural areas are often due to the chemical characteristics that influence leachability, solubility, and volatility of synthetic pesticides, which allow for movement off their target site, even when licensed applicators (for restricted-use pesticides) are being used at labeled rates recommended by the manufacturer and approved by EPA in the U.S. Chemical residues in air, land, water, and food result in aggregate exposure to multiple pesticides and their breakdown materials (metabolites), many of which bioaccumulate. Without adequate assessment of these complexities by pesticide regulatory systems, where they exist worldwide, Indigenous communities are on the frontlines of advocating for a more sustainable and just future.

In Brazil, there is an ongoing legislative battle over strengthening environmental governance at the expense of the safety of Indigenous communities. Panh-ĂŽ KayapĂł, an Indigenous woman from BaĂș Indigenous Territory and director of the Kabu Institute, said in an August 7 press release issued by Amazon Watch: âThis bill shows that Congress doesnât care about the Brazilian people. They want more profits for agribusiness and foreign companies, while regular people pay more for toxic food and suffer through droughts, floods, and the climate crisis. President Lula must veto this bill â itâs a matter of life and sovereignty.â This âdevastation bill,â as it is called, is the recently passed Bill 2159/2021, which would undermine regulatory agency authority by âexempt[ing] activities such as mining and soy and cattle production from formal licensing procedures by Brazilâs environmental agencies…despite the potential social-ecological consequencesâ according to an analysis by Federal University of Santa Catariana, Amazon Regional Observatory, Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization (ORA/OTCA), JuruĂĄ Institute, and University of Santiago de Compostela published in Science.

Irepoiti Metuktire, a Kayapo leader from the Kapot Nhinore Indigenous Territory and representative of the Ropni Women’s Department of the Raoni Institute, in response to the threat of chemical-intensive soybean production to Indigenous health and sovereignty, said: âThis soy doesn’t feed our people. We don’t eat soy – it’s for export and corporate profit. Meanwhile, pesticides contaminate our water, our soil, and even the rain. It’s poisoning all of us, not just Indigenous peoples. And food in the cities gets more expensive every day. Defending the forest is defending life for everyone.”

Previous Research

Pesticide residues have been found to drift across surprising distances through the air, water, and soil, based on decades of scientific literature that continues to emerge this troubling trend.

There is published research identifying various current-use pesticides in urine samples of an Inuit population in the rural area of Nunavik, Quebec. Published in 2024 in International Journal of Circumpolar Health, researchers at Boston University, Quebec-based institution Laval University, and the National Institute of Public Health of Quebec compared the biomarker levels of various pesticides known to be âcapable of long-range transportâ in an Indigenous community to the general Canadian population. Even though they did not find conclusive evidence of higher risk for this specific Inuit population, this “… study was the first to document environmental exposures to pesticides in an Arctic community using a cost-effective and reliable methodâ of analyzing urine sampling of the Inuit population, according to the authors. Chlorpyrifos, parathion, and several other pyrethroids and their metabolites were detected in the highest concentrations, which is consistent with other research.

In a survey-based study published in Journal of Environmental Health in 2023, approximately 11,326 participants identifying as âAmerican Indian and Alaska Nativeâ shared their experiences with occupational and environmental exposures for the Education and Research Towards Health (EARTH) Study in the Southwest U.S. and Alaska. Pesticides and petroleum ranked first and second among the most commonly reported hazards for participants in the Southwest U.S. The goal of this study was to provide âbaseline data to facilitate future exposure-response analyses.â

This research builds on calls from existing reports that emphasize the links between Indigenous communities’ environmental and occupational exposure to toxic chemicals, like pesticides, and severe health issues, such as cancer, neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, and chronic illnesses. A 2022 report published in The Lancet speaks to the systemic effects of pesticide policies in the U.S. and the failure of leadership in the United Nations to protect the Yaqui Nation in Mexico. The piece finds: âThe Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) is a U.S. statute that allows “pesticides that are not approved â or registered â for use in the U.S.” to be manufactured in the U.S. and exported elsewhere. The UN Rotterdam Convention also allows the global exportation of “banned pesticides.â The ongoing exportation of banned pesticides leads to disproportionately high rates of morbidity and mortality, most notably in Indigenous women and children. (See Daily News here.)

Call to Action

It comes as no surprise that the focus of this yearâs International Day of the Worldâs Indigenous Peoples is on the impacts of AI on Indigenous communities, given the potential environmental implications as demands for data centers continue to mount globally and domestically. Organic, pesticide, and pollinator advocates stand in solidarity with the right of Indigenous communities to self-determination and advancing policies and systems that support their well-being, as much of the transformative change is inspired by the First Nations leadership in leading with nature, rather than in exploiting it to its inevitable destruction.

There are also the mounting concerns on artificial intelligence and pesticide development from scientists, bioethicists, and food sovereignty advocates in the European Union; Save our Seeds Foundation produced a report earlier this year warning of various threats that generative artificial intelligence would impose on the already flawed regulatory system, including data distortions and hallucinations, the lack of transparency in how AI agents or systems make their decisions, and the lower barrier that could lead to further unregulated and untested pesticide products. (See Daily News here.)

In response to the proliferation of dangerous pesticide products threatening Indigenous and general populations, you can take action here by telling EPA to ban the use of the herbicide dicamba and other drift-prone pesticides.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Sources: United Nations, Amazon Watch, Science, International Journal of Circumpolar Health

Posted in Chlorpyrifos, Drift, Environmental Justice, Indigenous People, Native Americans, Occupational Health, Parathion, Pesticide Drift, pyrethroids, Uncategorized by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

11

Aug

(Beyond Pesticides, August 11, 2025)Â With the reintroduction of legislation in July to support organic dairy production, Beyond Pesticides is calling on the public to support small organic farms that are hurting because of feed shortages, increased costs, and low premium to farmers, despite higher prices at the grocery store. Beyond Pesticides has called for an investment in organic as a long-term investment in the public good, given the value that organic brings as a solution to the health, biodiversity, and climate crises. (See previous Daily News, here and here.)

Legislation, the Organic Dairy Assistance, Investment, and Reporting Yields Act (O DAIRY Act), S. 2442, introduced by U.S. Senator Peter Welch (D-Vt.), Ranking Member of the Senate Agriculture Subcommittee on Rural Development, Energy, and Credit, along with Senators Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), and Cory Booker (D-N.J.) will expand federal support for organic dairy farmers by extending emergency assistance to farmers facing losses due to factors like feed shortages and increased costs. The Senators’ legislation also increases investments in the organic dairy industry to ensure resiliency and longevity and works to improve data collection for organic milk production to enhance price accuracy and transparency.âŻBeyond Pesticides is suggesting that the public Tell U.S. Senators to cosponsor the O DAIRY Act, S. 2442.Â

Analysts point to the growing market for organic milk, driven by consumer demand, as supported by clinical studies, for hormone-free, antibiotic-free, and non-GMO products, as well as environmentally friendly production methods. Organic milk also provides more omega-3 fatty acids, disease-fighting antioxidants, and essential minerals than non-organic milk. Â

In spite of the rising demand for organic milk, organic dairiesâparticularly the smaller dairiesâare not prospering. Small producers have little bargaining power with buyers. In addition, organic dairies have costly overhead, including providing consistent pasture, which is expensive in today’s booming land markets. Organic dairies must maintain production and herd health without resorting to antibiotics, hormones, and other chemicals. As a result, according to Matthew Dillon, co-CEO of the Organic Trade Association, the U.S. has lost 13% of organic dairy producers since 2021.Â

The O DAIRY Act will extend emergency assistance to organic dairy farmers facing losses, including any time a farm’s net income decreases by over 10% in any given year, and invest $25 million annually in dairy infrastructure investments, research, and innovation. The legislation also calls for increased organic industry data collection that will be shared with farmers for better planning. Additionally, the bill would direct USDA to study the viability of an organic safety net program, which would provide aid to farmers faster when disasters hit.âŻÂ

The O DAIRY Act has the broad support of farms, dairy cooperatives, producers, and associations across the country.Â

Readers can Tell your U.S. Senators to cosponsor the O DAIRY Act, S. 2442.Â

Letter to U.S. Senators [Request to cosponsor]:

Analysts point to the growing market for organic milk, driven by consumer demand, as supported by clinical studies, for hormone-free, antibiotic-free, and non-GMO products, as well as environmentally friendly production methods. Organic milk also provides more omega-3 fatty acids, disease-fighting antioxidants, and essential minerals than non-organic milk.

In spite of the rising demand for organic milk, organic dairiesâparticularly the smaller dairiesâare not prospering. Small producers have little bargaining power with buyers. In addition, organic dairies have costly overhead, including providing consistent pasture, which is expensive in todayâs booming land markets. Organic dairies must maintain production and herd health without resorting to antibiotics, hormones, and other chemicals. As a result, according to Matthew Dillon, co-CEO of the Organic Trade Association, the U.S. has lost 13% of organic dairy producers since 2021.

In order to address the problems facing organic dairies, U.S. Senator Peter Welch (D-Vt.), Ranking Member of the Senate Agriculture Subcommittee on Rural Development, Energy, and Credit, along with Senators Kirsten Gillibrand (D-N.Y.), Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.), and Cory Booker (D-N.J.) reintroduced the Organic Dairy Assistance, Investment, and Reporting Yields Act (O DAIRY) Act, S. 2442, legislation to expand federal support for organic dairy farmers by extending emergency assistance to farmers facing losses due to factors like feed shortages and increased costs. The Senatorsâ legislation also increases investments in the organic dairy industry to ensure resiliency and longevity and works to improve data collection for organic milk production to enhance price accuracy and transparency.âŻâŻ

The O DAIRY Act will extend emergency assistance to organic dairy farmers facing losses, including any time a farmâs net income decreases by over 10% in any given year, and invest $25 million annually in dairy infrastructure investments, research, and innovation. The legislation also calls for increased organic industry data collection that will be shared with farmers for better planning. Additionally, the bill would direct USDA to study the viability of an organic safety net program, which would provide aid to farmers faster when disasters hit.âŻ

The O DAIRY Act has the broad support of farms, dairy cooperatives, producers, and associations across the country. I hope I can count on you to cosponsor S. 2442 and support organic dairy farmers.

Thank you!

Letter to U.S. Senators [Thank you to sponsors]:

Analysts point to the growing market for organic milk, driven by consumer demand, as supported by clinical studies, for hormone-free, antibiotic-free, and non-GMO products, as well as environmentally friendly production methods. Organic milk also provides more omega-3 fatty acids, disease-fighting antioxidants, and essential minerals than non-organic milk.

In spite of the rising demand for organic milk, organic dairiesâparticularly the smaller dairiesâare not prospering. Small producers have little bargaining power with buyers. In addition, organic dairies have costly overhead, including providing consistent pasture, which is expensive in todayâs booming land markets. Organic dairies must maintain production and herd health without resorting to antibiotics, hormones, and other chemicals. As a result, according to Matthew Dillon, co-CEO of the Organic Trade Association, the U.S. has lost 13% of organic dairy producers since 2021.

In order to address the problems facing organic dairies, I appreciate your leadership in reintroducing the Organic Dairy Assistance, Investment, and Reporting Yields Act (O DAIRY) Act, S. 2442, legislation to expand federal support for organic dairy farmers by extending emergency assistance to farmers facing losses due to factors like feed shortages and increased costs. This legislation also increases investments in the organic dairy industry to ensure resiliency and longevity and works to improve data collection for organic milk production to enhance price accuracy and transparency.âŻâŻ

The O DAIRY Act will extend emergency assistance to organic dairy farmers facing losses, including any time a farmâs net income decreases by over 10% in any given year, and invest $25 million annually in dairy infrastructure investments, research, and innovation. The legislation also calls for increased organic industry data collection that will be shared with farmers for better planning. Additionally, the bill would direct USDA to study the viability of an organic safety net program, which would provide aid to farmers faster when disasters hit.âŻ

The O DAIRY Act has the broad support of farms, dairy cooperatives, producers, and associations across the country. Thank you once again for your leadership in support of organic dairy farmers.

Thank you!

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Posted in Alternatives/Organics, Congress, Farm Bill, Federal Agencies, Genetic Engineering, Livestock, Organic Foods Production Act OFPA, Take Action, Uncategorized, US Department of Agriculture (USDA) by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

08

Aug

(Beyond Pesticides, August 8, 2025) In a study published in Environmental Pollution, researchers have detected eighty pesticides (35 insecticides, 29 fungicides, and 11 herbicides, and metabolites) in the ambient air of a rural region of Spain (Valencia) between 2007 and 2024. Despite these dramatic findings, the authors conclude that there is âno [observable] cancer risk,â âno inhalation risk for adults,â and only one pesticide concentration (the insecticide chlorpyrifos) showing âa potential risk to toddlers.â However, the authors did not conduct an aggregate risk assessment that would typically consider all routes of exposure to the individual pesticides detected, including through water, food, and landscapes.

Not considered by the authors are the potential effects of pesticide mixtures and full pesticide product formulations (with all potentially toxic ingredients), also a deficiency in the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) registration of pesticides under federal law. Of concern, as well, are other contaminants in pesticide products, including but not limited to per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), heavy metals, plastics (including microplastics), which contribute to chronic diseases and health risks, and adverse effects to ecosystem stability exacerbated by the climate crisis.

Background and Methodology

âThis work aims to conduct a further study on the situation of pesticides in ambient air of a rural Mediterranean Region, describing spatial and temporal variations in pesticide uses, as well as a human health risk assessment based on pesticide inhalation exposure,â according to the study authors. They gathered 717 air samples at 12 locations in the rural agricultural region of Valencia, with nine sites considered ârural/agricultural,â two âurbanâ sites, and one remote site that serves as a control for this experiment. The researchers used three different sampling protocols over the 18-year-long study. Between 2007 and 2016, they used high-volume air samplers to capture particulate phase samples on a daily basis; meanwhile, between 2016 and 2024, they used low-volume samplers to gather particulate and gaseous phase (to account for volatilization) samples on a weekly basis. The third protocol (2008-2009) was supplementary sampling at four stations to capture gaseous phase samples that were previously missing. Since atmospheric pesticide presence can be detected in both the particulate and gaseous phases, the researchers were careful to capture both in their study.

The authors are based at CEAM Foundation (âa research, development and technological innovation center for the improvement of the environment in the Mediterranean areaâ), Research Institute for Pesticides and Water at Jaume I University, and Foundation for the Promotion of Health and Biomedical Research in the Valencia Region. They âdeclare[d] that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.â They received funding from the Ministry of Agriculture, Livestock, and Fisheries (Spain), with some of the analytical support being âfinanced by the European Commission under the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Operational Programme of the Valencia Region (2014â2020).â

Discussion and Results

The researchers targeted 120 pesticides in this study, with 80 different insecticides, fungicides, herbicides, acaricides, and metabolites detected:

- 35 insecticides were detected. (Chlorfenvinphos, Abamectin, Chlorpyrifos-methyl, Spinosad, Diphenylamine, Chlorpyrifos-ethyl, Dichlorvos, Methidathion, Hexythiazox, Ethoprophos, Omethoate, Pyriproxyfen, Acetamiprid, Alpha-Endosulfan, Beta-Endosulfan, Bendiocarb, Bifenthrin, Buprofezin, Carbofuran, Cypermethrin, Deltamethrin, Diazinon, Dimethoate, Dioxacarb, Fenazaquin, Fenthion, Fipronil, Flufenoxuron, Imidacloprid, Lambda-cyhalothrin, Malathion, Permethrin, Pirimicarb, Pirimicarb-desmethyl, Propargite, Spirotetramat, Tebufenpyrad, and Thiamethoxam.)

- 29 fungicides were detected. (Azoxystrobin, Benalaxyl-M, Bitertanol, Boscalid, Carbendazim, Chlorothalonil, Cyproconazole, Cyprodinil, Diphenylamine, Fenbuconazole, Fludioxonil, Flusilazole, Folpet, Imazalil, Iprodione, Iprovalicarb, Kresoxim-m, Metalaxyl, Myclobutanil, O-Phenylphenol, Penconazole, Prochloraz, Pyrimethanil, Tebuconazole, Thiabendazole, Triadimefon, Tricyclazole, Triflumizole, and Vinclozolin.)

- 11 herbicides were detected. (Benfluralin, Chlorpropham, Dichlobenil, Diuron, Endothal, Fluazifop, Glyphosate, Propachlor, Propanil, Terbuthylazine, and Trifluralin.)

- 5 additional pesticides and metabolites were detected. (Prohexadione, Terbuthylazine-2-OH, Terbuthylazine-desethyl, Terbuthylazine-desethyl-2-OH, and Endosulfan-sulphate.)

“The ten most frequently detected pesticides were spirotetramat (83 %), glyphosate (65 %), terbuthylazine-desethyl-2-OH (59 %), metalaxyl (56 %), carbendazim and pyriproxyfen (51 %), omethoate (46 %), spinosad (44 %), terbuthylazine (44 %), and chlorpyrifos-ethyl (43 %),â says the authors. There were significant declines in detectable carbendazim, omethoate, and terbuthylazine, which the authors believe correlate with European Union bans or restrictions.

There are various limitations to this study, including that there was no risk assessment included for subgroups that face disproportionate risks, including pregnant individuals. As mentioned earlier, this study was also not comprehensive in that it did not detect potential contamination or exposure via soil, water (surface or groundwater), dietary intake, and bioaccumulation. That being said, it is significant in that it is considered the first long-term (more than 15 years) regional study of pesticide air monitoring in the Mediterranean.

Previous Research

Pesticide residues are being found in increasingly remote locations across the globe. Documented for the first time, 15 currently used pesticides (CUPs) and four metabolites (breakdown or transformation productsâTP) were found in the deep marine atmosphere over the Atlantic Ocean. Three legacy (banned) pesticides were also discovered. According to the recent study published in Environmental Pollution, researchers found empirical evidence for pesticide drift over remarkably long distances to remote environments. (See Daily News here.)

People face multiple avenues of pesticide exposure and may be unwittingly subject to multiple exposures even if they do not live or work in agricultural areas/professions. A study published in Environmental Science and Technology found that there are 47 current-use pesticidesâproducts with active ingredients that are currently registered with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) âdetected in samples of indoor dust, drinking water, and urine from households in Indiana. (See Daily News here.) There are other peer-reviewed studies documenting the presence of pesticide residues in indoor dust samples. A large European study of house dust contaminants, published in Science of the Total Environment, finds more than 1,200 anthropogenic compounds, including numerous organophosphates, the phthalate DEHP, PCBs, pharmaceuticals, and personal care products, in indoor dust samples. Additionally, an Argentine study centered around households with nonagricultural workers found that all dust samples contained mixtures, averaging 19 pesticides per sample and with a maximum of 32 per sample. Twelve pesticides were detected in more than 75 percent of the samples. Imidacloprid, carbaryl, glyphosate, and atrazine were detected in all samples. Seven of the 49 are used as both agricultural and veterinary or household pest compounds. (See Daily News here.)

It is also critical that studies are conducted specifically on pregnant individuals. In a first-of-its-kind series of biomonitoring studies published in Agrochemicals, researchers identified the presence of the herbicides dicamba and 2,4-D in all pregnant participants from both cohorts in 2010-2012 and 2020-2022. Â âThe overall level of 2,4-D use (kilograms applied in one hundred thousands) in the U.S. was highest in 2010 for wheat, soybeans, and corn. The amount of 2,4-D applied increased the most for soybeans and corn from 2010 to 2020.â The researchers focused on the states of Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio, given the increase in dicamba and 2,4-D during the study period for both cohorts (2010-2022). (See Daily News here.) A comprehensive literature review in Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety links a heightened risk of spontaneous abortion (SAB) with pesticide exposure. âThe strengths of our study include being the first systematic review and meta-analysis to explore the association between exposure to pesticides and the risk of SAB,â the authors say. This novel approach incorporated the analysis of 18 studies, totaling 439,097 pregnant participants, which allowed the researchers to highlight an important public health issue and raise concerns for maternal contact with the harmful chemicals in pesticide products. (See Daily News here.) Ongoing exposure to pesticide residues in indoor and outdoor environments poses broader neurodevelopmental consequences for children. A study in Environment International finds that young children who exhibit higher levels of pesticide metabolites in their urine show more pronounced neurobehavioral problems at the age of ten. (See Daily News here.)

Call to Action

Communities across the nation are speaking out to elected officials about the threat of aerial pesticide spraying to their loved ones. Earlier this year, in 2025, protests were held in various California counties (see Inside Climate News and KSBW8 Action News) over the controversial continued use of the carcinogenic 1,3-Dichloropropene (1,3-D) in spite of its ban in over 40 countries and links to cancer. Communities in Oregon have mobilized for years against the aerial spraying of pesticides into public lands, including Lincoln County, which faced a setback to local control of pesticide use when a court ruled against a pesticide ordinance due to preemption language codified in state law in previous sessions. (See Daily News here.) Protests this year in Iowa and North Dakota were organized as their state legislatures voted on preempting the ability for victims of pesticide exposure to sue manufacturers for misleading labels that fail to warn of health risks. (See Daily News here.)

You can become an advocate too! Consider subscribing to the Action of the Week and Weekly News Update to stay informed on how and when to take action. You can also sign up and become an advocate for the Parks for a Sustainable Future Program.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Environmental Pollution

Posted in Abamectin, acetamiprid, air pollution, Azoxystrobin, Bendiocarb, Bifenthrin, boscalid, Carbendazim, Carbofuran, Chemicals, Chlorothalonil, Chlorpyrifos, cypermethrin, Deltamethrin, Diazinon, Dichlorvos, Dimethoate, Diuron, Endosulfan, endothall, Ethoprop, fenbuconazole, Fenthion, Fipronil, fludioxonil, Glyphosate, Imidacloprid, lambda-cyhalothrin, Malathion, Methidathion, Permethrin, Pesticide Drift, pirimicarb, Propargite, Pyriproxyfen, spinosad, Thiamethoxam, Trifluralin, Uncategorized, vinclozolin by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

07

Aug

(Beyond Pesticides, August 7, 2025) The novel study published in Arthritis & Rheumatology is the largest investigation of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in women to date, finding evidence of heightened risks when exposed to insecticides through data collected from over 400 eligible women in the Agricultural Health Study (AHS). AHS participants include a cohort of thousands of licensed pesticide applicators and their spouses from Iowa and North Carolina, with this particular study as the first to consider the link between pesticide exposure and RA as it affects womenâs health. Â

âGrowing evidence suggests farming and agricultural pesticide use may be associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but few studies have examined specific pesticides and RA among farm women, who may personally use pesticides or be indirectly exposed,â the study authors explain. The findings reveal that organochlorine insecticides that continue to persist in the environment, as well as organophosphate and synthetic pyrethroid pesticides used in public health or residential settings, correlate with RA diagnoses in women.Â

As shared in previous Daily News, for the most part organochlorine pesticides, including dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT), are no longer used worldwide, but the legacy of their poisoning and contamination persists. These compounds are primarily made up of chlorine atoms, classified as persistent organic pollutants (POPs) due to their toxic longevity in the environment. Although many countries ban most organochlorine compounds, the chemicals remain in soils, water (solid and liquid), and the surrounding air at levels exceeding U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standards. While EPA has ended pesticide registration for virtually all of the original POPs, the United States has not joined over 150 countries in ratifying a 2001 United Nations treaty known as the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, which requires the elimination of POPsâ production, use, and/or release.Â

Of the participants in the current study who report using pesticides, â[p]ersonal use of organochlorine insecticides was associated with incident RA, especially DDT and lindane,â the researchers say. Regarding organophosphate insecticides, a weaker association is seen apart from coumaphos and malathion. For carbamate insecticides, carbofuran use is associated with RA, as is the use of synthetic pyrethroid insecticides like permethrin and fungicides including captan and metalaxyl. Of the women who do not report personal use of pesticides, RA is associated with their spousesâ use of carbaryl, metribuzin, and maneb/mancozeb. Increased risks are also noted for indirect exposure to DDT, toxaphene, coumaphos, captan, metalaxyl, and malathion.Â

Rheumatoid arthritis, one of many types of arthritis, is classified as a systemic autoimmune disease that causes joint inflammation and pain. The disease involves both genetic and environmental risk factors, with many factors and triggers still unknown. According to the Arthritis Foundation, 1.5 million people in the U.S. have rheumatoid arthritis, with women three times more likely than men to develop the disease. A study by the Centers for Disease Controlâs (CDC) National Center for Health Statistics finds that the percentage of adults with arthritis increases in nonmetropolitan areas when compared to metropolitan areas, highlighting the potential role of agriculture and environmental contaminants.Â

Additional research (see here and here) suggests that, âRA may be associated with farming and pesticide use, but less is known about risks for women living on farms and the role of specific pesticides is not well understood.â With women already more likely to develop RA, exposure to environmental contaminants, such as pesticides, exacerbates the risks.Â

In the current study, the researchers review 410 cases of RA reported in women within the AHS cohort. The diagnoses were identified by self-reporting and then confirmed through validation, medication, and/or Medicare claims data. âWe examined incident RA and personal pesticide use (including overall type, classes, and 32 specific pesticides), considering correlated pesticides and farming tasks, and explored associations with potential indirect exposures through applicator use among women who did not personally apply specific pesticides,â the authors state.Â

In assessing farming activities, the study also finds RA is associated with several other chemicals used in chemical-intensive agriculture, including but not limited to cleaning with solvents, grinding feed, applying fertilizers, and planting. âThe AHS offers a unique opportunity to investigate RA risk in relation to specific pesticide types,â the researchers note. They continue, âWith nearly 10 additional years of follow-up and more than 3-times as many cases than previous AHS reports on RA in spouses, this study of incident RA provides robust evidence that some insecticides may increase RA risk among women.â Â

These results add to a growing body of science that suggests both direct and indirect exposure to pesticides can increase the risk of RA in women. (See here and here.) Studies show that pesticides can impact the development of RA through multiple pathways that are both direct (immunotoxic) or indirect (neuroendocrine, microbiome). As the authors state, âPathogenesis [how the disease develops] of RA includes several pathways by which pesticide immune effects may play a role, including antigen citrullination and presentation, autoantibodies production, dysregulated innate and adaptive immune function, and local and systemic inflammation.âÂ

Previous research shows that DDT contributes to inflammation and decreases the bodyâs response to infection, as well as the immunosuppressive effects of malathion and lindane. The triazine herbicide metribuzin also has reported toxicity for endocrine and hepatic effects, in addition to impacts on neurological and immune pathways.Â

âSeveral pesticides associated with RA in this study have been associated with other diseases indicative of immune dysregulation among AHS spouses, including maneb/mancozeb and metalaxyl with hypo- or hyperthyroid diagnoses (mostly autoimmune, i.e., Graveâs or Hashimotoâs disease), and malathion, permethrin/pyrethroids, and metribuzin (asthma),â the researchers report. (See more information on immune system disorders and autoimmune diseases here and here.)Â

In finding a greater RA risk in females, this suggests a role of both endogenous (internal) and exogenous (external) hormonal exposures and pathways. Research shows that insecticides, including the organochlorines DDT and lindane and the organophosphates carbofuran and malathion, can impact hormone receptors and affect female reproductive function. Similar findings to the current study, from the Womenâs Health Initiative Observational Study, also highlight the connection between insecticides and a heightened risk of RA, particularly among post-menopausal women who lived or worked on farms.Â

Previous Beyond Pesticides Daily News coverage, titled Exposure to Widely Used Bug Sprays Linked to Rheumatoid Arthritis, shows that exposure to widely used synthetic pyrethroids, present in many mosquito adulticides and household insecticides like RAID, is associated with a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis, according to research published in Environmental Science and Pollution Research. Â

The same pyrethroid metabolite was later found to be associated with increased osteoarthritis risk among U.S. adults, as shared in the Daily News Popular Pyrethroid Insecticides, Already Linked to Rheumatoid Arthritis, Associated with Osteoarthritis. In detecting levels of harmful compounds within the body, and connecting the high concentrations to diseases like arthritis, this study is one of many whose findings suggest the importance of an organic diet.Â

While certain diseases like arthritis have no cure, adopting an organic diet can eliminate exposure to toxic chemicals that increase disease risk. Studies show that switching to an organic diet can reduce pesticide levels in urine within just two weeks, and that organic agricultural practices and maintaining an organic diet reveal evidence of reduced concentrations of metabolites and lower body burden.Â

Beyond Pesticides urges farmers to embrace regenerative organic practices and for consumers to support this holistic, systems-based approach to land management by buying organic products (even on a budget!) or growing organic food. Learn more about the health benefits of organic agriculture here, and stay engaged by signing up to receive Action of the Week and Weekly News Updates delivered straight to your inbox here.Â

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides. Â

Source:Â

Parks, C. et al. (2025) Associations of specific pesticides and incident rheumatoid arthritis among female spouses in the Agricultural Health Study, Arthritis & Rheumatology. Available at: https://acrjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/art.43318.Â

Posted in Agriculture, Alternatives/Organics, Arthritis/Joint Inflammation, Carbamates, Carbaryl, Carbofuran, Coumaphos, DDT, Fungicides, Lindane, Malathion, mancozeb, Maneb, Metalaxyl, organochlorines, organophosphate, Permethrin, pyrethroids, Rheumatoid arthritis, Synthetic Pyrethroid, Women's Health by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

06

Aug

(Beyond Pesticides, August 6, 2025) A study published in Science of The Total Environment finds that âchronic pesticide exposure alters metabolism and impairs fish growth and health.â

With increasing concern about the long-term consequences of pesticide persistence in ecosystems, the scientific literature continues to expand the body of research findings on adverse effects, including impacts on marine or aquatic ecosystems and organisms. Given the known and growing risks, there is an ongoing movement to move beyond petrochemical-based chemicals for agriculture and land management by adopting policies and programs that advance organic criteria and principles, as outlined in national organic law and practiced by tens of thousands of certified farmers and land managers across the country, and even more at the international level.

Background and Methodology

âThe objective of this study was to assess the physiological responses of juvenile P. lineatus exposed to environmentally relevant pesticide mixtures by integrating multiple biological endpoints across sub-individual and organismal levels,â the authors write.

The study was conducted at two sites in the Tibagi River watershed located in ParanĂĄ, a southern region in Brazil. There was a reference site (RFS) and an agricultural site (AGS), the former having minimal pesticide contamination and the latter having been managed with pesticides. The test organism for this study was the six-month-old Prochilodus lineatus (a native Neotropical freshwater fish), which is a keystone species known for its contribution âto nutrient cycling, energy flow, and sediment bioturbation [mixing of soil materials by living organisms].â The fish were exposed for 120 days, with sampling conducted at days 5, 15, 30, 60, 90, and 120.

The authors gathered biomarkers on hematological, metabolic, neurological, and histopathological data at the sub-individual level, as well as organism-level endpoints, including growth rates (absolute and specific), somatic indexes on overall nutritional health (Fultonâs Condition and Liver Somatic Index), and behavior (Swimming Endurance Index). More information can be found in the methodology section of the study. The researchers analyzed 22 organochlorine (legacy) and 33 current-use pesticides in the water samples. While the paper does not include a full list of the 55 pesticides in the study, the fungicide carbendazim, the insecticide fipronil, and the insecticide breakdown product endosulfan sulfate are specifically mentioned in terms of significant findings. The data was analyzed through three tools: Two-Way analyses of variance (Two-Way Anova) to test for significance, Principal Component Analysis (PCA), and Integrated Biomarker Response (IBR) index. PCA is used to better understand patterns among the various biomarkers over the course of the experiment, and the IBR index is used to combine and summarize biomarker responses into one number.

The authors are researchers at the State University of Londrina in Brazil, based in the Physiological Sciences Department. The authors declare âno known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.â The authors acknowledge the financial support of the Brazilian Council for Scientific and Technological Development and funding from the Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel in support of one of the PhD student co-authors on the study.

Results

The authors successfully answered their hypothesis that âchronic pesticide exposure elicits compensatory and adaptive responses in fish, increasing energetic demands and ultimately compromising growth and swimming performance.â

More specifically, AGS (agricultural site) fish exhibit various metabolic and hematological disruptions, including increased blood glucose, elevated hematocrit (percentage of red blood cells compared to blood volume), and high hemoglobin levels early in the exposure period, which the authors believe is indicative of an acute stress response. AGS fish were found to face transient inhibition of acetylcholinesterase (AChE) activity in the muscle and brain, which the authors suggest could be attributed to neurotoxic pesticide exposure, such as organophosphates.

As mentioned earlier, the authors mention carbendazim, fipronil, and endosulfan sulfate specifically, given that these compounds were detected at higher concentrations at the AGS site than at the RFS (reference or control) site. These active ingredients are linked to altered energy metabolism and growth suppression, with fipronil specifically linked to the inhibition of acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme necessary for nervous system functioning.

In terms of data analysis, IBR scores were higher at the AGS site, which the authors indicate as having greater overall stress and biological disruption. Additionally, the PCA analysis (found in Figures 8 and 9) finds that pesticide exposure was a primary driver for these physiological changes in demonstrating site- and time-dependent clustering of various biomarker responses.

Previous Research

Freshwater organisms and ecosystems are at serious risk of collapse given the cumulative exposure to pesticides, microplastics, and other toxic substances, as documented in the literature. One of the most recent studies to demonstrate this, published in Ecotoxicology, focuses on the impacts of MPs and chlorpyrifos (CPF), a widely used organophosphate insecticide, on cladocerans, a group of microcrustaceans. Chronic exposure shows reduced survival and reproductive output in both cladoceran species in this study. (See Daily News here.) A 2025 study, published in Environmental Pollutants and Bioavailability, assesses the impacts on Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), with subacute and chronic exposure to thiamethoxam, a neonicotinoid insecticide, and finds genotoxicity, oxidative stress (imbalances affecting the bodyâs detoxification abilities that lead to cell and tissue damage), and changes in tissue structure, among other threats to organ function and overall fish health. (See Daily News here.)