(Beyond Pesticides, October 1, 2021) With this article, Beyond Pesticides rounds out its coverage of recent revelations about compromised science integrity at the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). As Sharon Lerner reports in her September 18 (and third in a series) article in The Intercept, new documents and whistleblower interviews reveal additional means by which EPA officials have gone out of their way to avoid assessing potential health risks of hundreds of new chemicals. Ms. Lerner writes that ‚Äúsenior staff have made chemicals appear safer ‚ÄĒ sometimes dodging restrictions on their use ‚ÄĒ by minimizing the estimates of how much is released into the environment.‚ÄĚ Beyond Pesticides regularly monitors and reports on scientific integrity at EPA, including two recent articles that reference Ms. Lerner‚Äôs The Intercept reporting; see ‚ÄúEPA Agenda Undermined by Its Embrace of Industry Influence,‚ÄĚ and ‚ÄúWhistleblowers Say EPA Managers Engaged in Corrupt and Unethical Practices, Removed Findings, and Revised Conclusions.‚ÄĚ

Whistleblowers had already provided evidence of agency malfeasance, particularly in EPA‚Äôs New Chemicals Division (NCD), such as ‚Äúmanagers and other officials . . . pressuring [EPA scientists] to assess chemicals to be less toxic than they actually are ‚ÄĒ and sometimes removing references to their harms from chemical assessments.‚ÄĚ Now, these career scientists have added new revelations to that tranche of disturbing information, evidenced by internal emails, meeting summaries, screenshots from EPA‚Äôs internal computer system, and testimony offered in interviews with them and other EPA scientists.

In its August 6 Daily News Blog article, Beyond Pesticides also wrote about the whistleblowers‚Äô experiences of management retaliation for their outspokenness and advocacy for public health ‚ÄĒ including functional reassignment or demotion. A high-profile case is that of Ruth Etzel, MD, PhD, the former director of the EPA‚Äôs Office of Children‚Äôs Health Protection, who is among the (now five) current or former EPA scientists who have¬†recently come forward¬†with allegations of corruption at the agency. Dr. Etzel maintains that EPA officials tried to silence her because of her insistence on stronger lead poisoning prevention programs. She was¬†placed on leave¬†without pay in September 2018; in a mid-September 2021 hearing before the federal Merit Systems Protection Board she testified that EPA had ‚Äúissued public statements designed to discredit and intimidate her,‚ÄĚ and that the agency has become deeply corrupted by corporate and political influence.

A little context for the recent revelations: EPA uses two measures to assess a chemical‚Äôs potential health risks. One is its toxicity; the other is the amount of the compound people are likely to be exposed to in the environment. Previous whistleblower evidence, as noted above, shows that officials have pressured agency scientists to distort toxicity assessments. On the exposure front: since 1995, EPA has operated under a rubric that says, basically, if exposures are below a given threshold ‚ÄĒ the ‚Äúbelow modeling threshold‚ÄĚ ‚ÄĒ safety is presumed. If exposures are considered to rise above that threshold, EPA scientists are required to quantify the precise risk posed by the chemical.

However, in recent years, scientists have determined that ‚Äúsome of the chemicals allowed onto the market using this [threshold] loophole do in fact present a danger, particularly to the people living in ‚Äėfence-line communities‚Äô near industrial plants,‚ÄĚ or proximate to other sources of chemical pollution, including chemically managed (with synthetic pesticides) agricultural fields. Agency scientists became increasingly concerned, given emerging information on low-level exposures, that use of these ‚Äúexposure thresholds‚ÄĚ might be putting the public at unnecessary risk, including for cancers.

The recent reports from whistleblowers indicate that in 2018, a manager in EPA‚Äôs Office of Pollution Prevention and Toxics (OPPT) instructed agency scientists ‚Äúto change the language they used to classify chemicals that were exempted from risk calculation because they were deemed to have low exposure levels. Up to that point, they had described them in reports as ‚Äėbelow modeling thresholds.‚Äô From then on, the manager explained, the scientists were to [use] the words ‚Äėexpects to be negligible‚Äô ‚ÄĒ a phrase that implies there‚Äôs no reason for concern.‚ÄĚ

Several of the scientists involved with risk calculations were unhappy about this; they also understood that using this ‚Äúthreshold‚ÄĚ protocol leaves people at risk for health effects of low-level chemical exposures. They suggested to managers that instead, the thresholds be lowered so as to capture more risk data, and that they do calculations for each individual chemical under consideration ‚ÄĒ a task they noted would add mere minutes to their assessment process.

But, as Ms. Lerner reports, ‚ÄúThe managers refused to heed their request, which would have not only changed how chemicals were assessed moving forward, but would have¬†also had implications for hundreds of assessments in the past. ‚ÄėThey told us that the use of the thresholds was a policy decision and, as such, we could not simply stop applying them,‚Äô one of the scientists who worked in the office explained to The Intercept.‚ÄĚ Documents provided by some whistleblowers show that NCD managers have repeatedly been unresponsive to or dismissive of calls to change that policy ‚ÄĒ even when scientists have demonstrated that it puts the public at risk.

In February 2021, a small group of agency scientists reviewed EPA‚Äôs ‚Äúsafety‚ÄĚ thresholds for every one of the 368 new chemicals submitted to¬†the¬†agency in 2020.¬†They found that more than half of the chemicals could pose health risks ‚ÄĒ including chemicals whose exposure potentials had already been deemed ‚Äúexpect[ed] to be negligible,‚ÄĚ and thus, for which specific risk calculations had not been done. Once more, the scientists brought this issue to NCD managers, explained their analysis, and requested that the use of these thresholds be terminated. The response from division managers? Crickets. As The Intercept writes, ‚ÄúSeven months later, the thresholds remain in use and the risk posed by chemicals deemed to have low exposure levels is still not being calculated and included in chemical assessments.‚ÄĚ

Such problematic dynamics comprise a substantial part of what the EPA whistleblowers have reported, and would appear to be, efforts by senior staff to undermine and contravene EPA‚Äôs actual mission ‚ÄĒ ‚Äúto protect human health and the environment.‚ÄĚ The Intercept article quotes one of the two scientists who filed new disclosures with EPA‚Äôs Office of the Inspector General (OIG) on August 31: ‚ÄúOur work on new chemicals often felt like an exercise in finding ways to approve new chemicals rather than reviewing them for approval.‚ÄĚ

Ms. Lerner asks why it is that ‚Äúsome senior staff and managers within the EPA‚Äôs New Chemicals Division seem to feel an obligation not to burden the companies they regulate with restrictions.‚ÄĚ Advocates suggest a variety of answers. ‚ÄúThat‚Äôs the $64,000 question,‚ÄĚ commented PEER (Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility) Director of Science Policy Dr. Kyla Bennett. She has said that some career staff at EPA have been ‚Äúcaptured by industry.‚ÄĚ Government watchdog organizations, such as PEER, as well as Beyond Pesticides, have noted the dysfunctional ‚Äúrevolving door‚ÄĚ between EPA and industry. Dr. Bennett noted (in a PEER webinar attended by the author on September 22) that one agency manager moved back and forth between EPA and the private chemicals industry four times.

According to reporting by Carey Gillam for U.S. Right to Know (RTK), a¬†research project¬†out of Harvard University‚Äôs Edmond J. Safra Center for Ethics reported that, though EPA has ‚Äú‚Äėmany dedicated employees who truly believe in its mission,‚Äô the agency has been ‚Äėcorrupted by numerous routine practices,‚Äô including a ‚Äėrevolving door‚Äô between EPA and industry in which corporate lawyers and lobbyists gain positions of agency power, [and there is] constant¬†industry lobbying against environmental regulations, pressure from lawmakers who are beholden to donors, and meddling by the White House.‚ÄĚ

Dr. Bennett has noted that, ‚ÄúEPA staffers may enhance their post-agency job prospects within the industry if they stay in the good graces of chemical companies. . . . [and that] managers‚Äô performance within the division is assessed partly based on how many chemicals they approve. ‚ÄėThe bean counting is driving their actions,‚Äô said Bennett. ‚ÄėThe performance metrics should be, how many chemicals did you prevent from going onto the market, rather than how many did you get onto the market.‚Äô‚ÄĚ

Both Dr. Richard Denison of the Environmental Defense Fund, and Tim Whitehouse of PEER (the nonprofit that represents the whistleblowers and has filed complaints on their behalf with the OIG), have described the culture of the Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention, and of OPPT‚Äôs New Chemicals Division, especially. Dr. Denison has said, ‚ÄúNCD is a ‚Äėblack box‚Äô that courts excessive confidentiality claims from industry, withholds information from the public, and has an ‚Äėinsular, secretive culture‚Äô that works against the mission of EPA and the interests of the people.‚ÄĚ Mr. Whitehouse asserted that ‚Äúpolitics has overtaken professionalism among managers at EPA.‚ÄĚ

Dr. Denison also (in the September 22 webinar) pointed to the insularity of NCD, noting that it has little-to-no engagement with non-industry stakeholders, such as advocates in the health or labor sectors. Further, he charges the program with nurturing a ‚Äúculture of secrecy‚ÄĚ that results in failures to provide timely public access to industry data on chemicals or EPA‚Äôs own safety evaluations, and often yields massively redacted health and safety information. This violates stipulations of the Toxic Substances Control Act (TSCA), the authorizing law created in 1976 to protect the public from ‚Äúunreasonable risk of injury to health or the environment‚ÄĚ by regulating the manufacture and commercial sale of chemicals.

Ms. Lerner‚Äôs The Intercept article dives into specifics on how NCD‚Äôs failure to attend to low-level exposure risks is exacerbating cancer risks. Cancer is a health outcome that can result from even micro-exposures to certain chemical compounds; indeed, EPA‚Äôs Guidelines for Carcinogenic Risk Assessment instruct agency scientists ‚Äúto assume that there is no safe level of agents that are ‚ÄėDNA-reactive‚Äô and have ‚Äėdirect mutagenic activity.‚Äô‚ÄĚ In spite of this, NCD managers have inappropriately ignored or dismissed cancer risks about cancer risks based on the assumption that a chemical would be diluted in the air, according to evidence presented by the whistleblowers.

This was the case for at least two chemicals ‚Äúassessed‚ÄĚ in 2021. EPA¬†deemed¬†one of those (a component of adhesives) ‚Äúnot likely to present an unreasonable risk of harm.‚ÄĚ The other ‚ÄĒ a dialkyl sulfate that is one of a class of chemicals that causes cancer in animals ‚ÄĒ was one of 13 similar chemical submissions the agency received between June 2020 and August 2021.

According to a whistleblower‚Äôs account in late August, ‚ÄúEPA managers took several steps to make the dialkyl sulfate chemical appear safer than it really is. . . . Because they didn‚Äôt have sufficient testing of the¬†substance itself, the scientist assessing it chose a closely related compound to gauge its risks. But a manager replaced that analogue, which causes miscarriages in animal experiments, with another, less harmful chemical, which allowed the agency to officially dismiss concerns about harms to the developing human fetus.‚ÄĚ

In addition, exposure information was added to the dialkyl sulfate assessment without notification to the scientist who wrote it. The assessment indicated that the compound poses a cancer risk and acknowledged it could cause genotoxicity; a manager‚Äôs change to the assessment added language to indicate that ‚Äúgenotoxicity is not a concern ‚Äėdue to the dilution of the chemical substance in the media [such as the air].‚Äô‚ÄĚ

The scientists dissented, citing evidence that related compounds are known to remain in the air for at least eight days. Although EPA has not (officially) calculated potential cancer risks for all the submitted chemicals in the class, one of the whistleblowing scientists has ‚ÄĒ and found that some do represent significant cancer risks. In their complaint to the OIG, the scientists wrote: ‚ÄúThe Agency is failing to calculate potential cancer risks to the general population based on the fallacy that a chemical is expected to be ‚Äėdiluted‚Äô in the air. . . . You don‚Äôt always find risk when you look for it. But they‚Äôre not even trying.‚ÄĚ

The Intercept requested comment on its September 18 article from EPA; the agency referred the outlet to the same statement it had provided in response to the first two pieces in the series. As The Intercept wrote, ‚ÄúThat statement said, in part, ‚ÄėThis Administration is committed to investigating alleged violations of scientific integrity. It is critical that all EPA decisions are informed by rigorous scientific information and standards. As one of his first acts as Administrator, Administrator Regan issued a memorandum outlining concrete steps to reinforce the agency‚Äôs commitment to science.‚Äô‚ÄĚ

According to advocates, this seem to be a feeble response to reporting of malfeasance in EPA’s own house. The references to scientific integrity, they say, ring a bit hollow, given the flagrant violations of that very integrity alleged by the whistleblowers.

EPA does, indeed, have a Scientific Integrity Policy. It emphasizes the importance of adherence to professional values and practices when conducting and applying the results of science and scholarship. The policy is supposed to ensure objectivity, clarity, reproducibility, and utility, and to ‚Äúprovide insulation‚ÄĚ from bias, fabrication, falsification, plagiarism, outside interference, censorship, and inadequate procedural and informational security.

However, as PEER has written on its website, ‚ÄúDuring Trump‚Äôs tenure, the record indicates EPA‚Äôs Scientific Integrity program was inoperative and it has yet to revive. . . . EPA‚Äôs Scientific Integrity program is a beacon of false hope and, in that sense, is worse than useless.‚ÄĚ PEER goes on to enumerate the problems: ‚ÄúMajor hindrances in EPA‚Äôs Scientific Integrity program include the total lack of investigative staff, the inability to draw upon expertise needed to assess technical issues, and the absence of any protocol for reviewing or investigating complaints. Further, EPA‚Äôs Scientific Integrity Policy carries no penalties for violations. As a result, the only tool the program has is trying to persuade non-compliant managers to address their own violations when raised by their subordinates.‚ÄĚ

PEER reports that EPA‚Äôs last annual report on the Scientific Integrity (SI) program was in 2018. PEER obtained outcome data for the period from mid-2018 through mid-2021: 35 allegations were filed, 22 remained ‚Äúactive‚ÄĚ (i.e., unresolved), 12 had been closed or referred ‚ÄĒ and exactly one complaint was deemed ‚Äúsubstantiated.‚ÄĚ That case was about a staff allegation, brought in November 2020, that a memo that changed policy ‚ÄĒ such that human health assessments would be far less likely to find risk for new chemicals being evaluated ‚ÄĒ was ignored for months by managers.¬†

Of that case PEER writes, ‚ÄúThe allegations in the complaint were ‚Äėsustained,‚Äô and this resulted in managers temporarily revoking the policy memo in question. However, it appears that the memo may be reissued, and the altered assessments were not corrected. Notably, this was the only complaint classified as ‚Äėsustained‚Äô during the past 30 months.‚ÄĚ Dr. Kyla Bennett commented, ‚Äú‚ÄėIt has become clear that the only way to force EPA to address scientific malpractice is to avoid the Scientific Integrity program altogether and go public.‚Äô [She notes] that the Scientific Integrity program repeatedly acts as if it is a branch of Human Resources, seeking to deflect or suppress staff complaints. ‚ÄėEPA needs to stop protecting¬†managers who violate EPA‚Äôs scientific integrity policy¬†and deal with them appropriately.‚Äô‚ÄĚ

The above-referenced September 22 PEER webinar ‚ÄĒ a panel discussion of how EPA risk assessments for new chemicals have been improperly altered to eliminate or minimize risk calculations ‚ÄĒ surfaced a number of reforms promoted by PEER. (The webinar panelists were Dr. Kyla Bennett, Science Policy Director at PEER; Mindi Messmer, Co-founder of New Hampshire Science and Public Health and NH Safe Water Alliance; and Richard Denison, Lead Senior Scientist at the Environmental Defense Fund.)

The top-level recommendation is that NCD needs a ‚Äúmassive overhaul.‚ÄĚ More specifically, Drs. Denison and Bennett point to these reforms:

- There must be public access, early in the review process of a new proposed chemical, to documents submitted by industry and being generated by EPA with only legal redactions.

- The public must be able to weigh in on proposed new chemicals.

- All data need to be submitted before the 90-day clock starts ticking; a 30-day public comment period would be useful, with time allotted for consideration of comments before agency determination on a chemical.

- EPA managers or other officials who have engaged in corrupt practices should be publicly identified, terminated, and replaced.

- A pre-application meeting of agency scientists and the industry applicant before the application is submitted would be a wise initiative.

Dr. Denison commented that ‚Äúapplicant understanding of any agency concerns and what would alleviate them would be a fine thing; but to let industry strongly lobby for alteration of science or conclusions is awful. Any discussion of the science between EPA and industry must be publicly accessible.‚ÄĚ Dr. Bennett added, ‚ÄúPre-application discussion can be appropriate ‚ÄĒ a ‚Äėtell us what you need to make a good assessment‚Äô kind of conversation. This 90-day deadline drives some of the abuse. Industry must bring forward all the information needed to make science-based risk assessments; currently, EPA is often looking only at industry studies, or sometimes, receives no data at all.‚ÄĚ

In addition, improved protection of government whistleblowers should be a priority. As PEER asserts, ‚ÄúWe are all too aware of the precarious health of our planet, and to protect it we must also protect our democracy. Those who would enable the wholesale poisoning, bulldozing, and privatization of our nation can rely on exploiting flaws in our democratic processes, but we are in a unique position to correct those flaws.‚ÄĚ

The Protecting Our Democracy Act, or PODA, is a bill first introduced in 2020, and reintroduced in the House of Representatives on September 21, 2021. It contains many democracy-protective features, as well as more-robust protections of government whistleblowers. PEER continues: ‚ÄúThe Protecting Our Democracy Act is a critical patch to our nation‚Äôs operating system, correcting fundamental security flaws which have been exploited for far too long by malicious actors who want to see government and public protections for the environment emaciated, corrupted, or outright destroyed.‚ÄĚ

In July 2021, Beyond Pesticides added these recommendations: ‚ÄúEPA [must] recalibrate itself in alignment with a precautionary approach, and move aggressively and authoritatively on its protective mission. Other [important reforms] are: Congressional funding of the agency at levels required to perform well . . . [and] EPA Office of the Inspector General and Congressional crackdowns on the ability of industry to interact with the agency, and on the ability of the revolving door to continue to operate. The public can pressure elected officials to take up such measures; find your U.S. Senator and Representatives¬†here.‚ÄĚ

Source: https://theintercept.com/2021/09/18/epa-corruption-harmful-chemicals-testing/

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

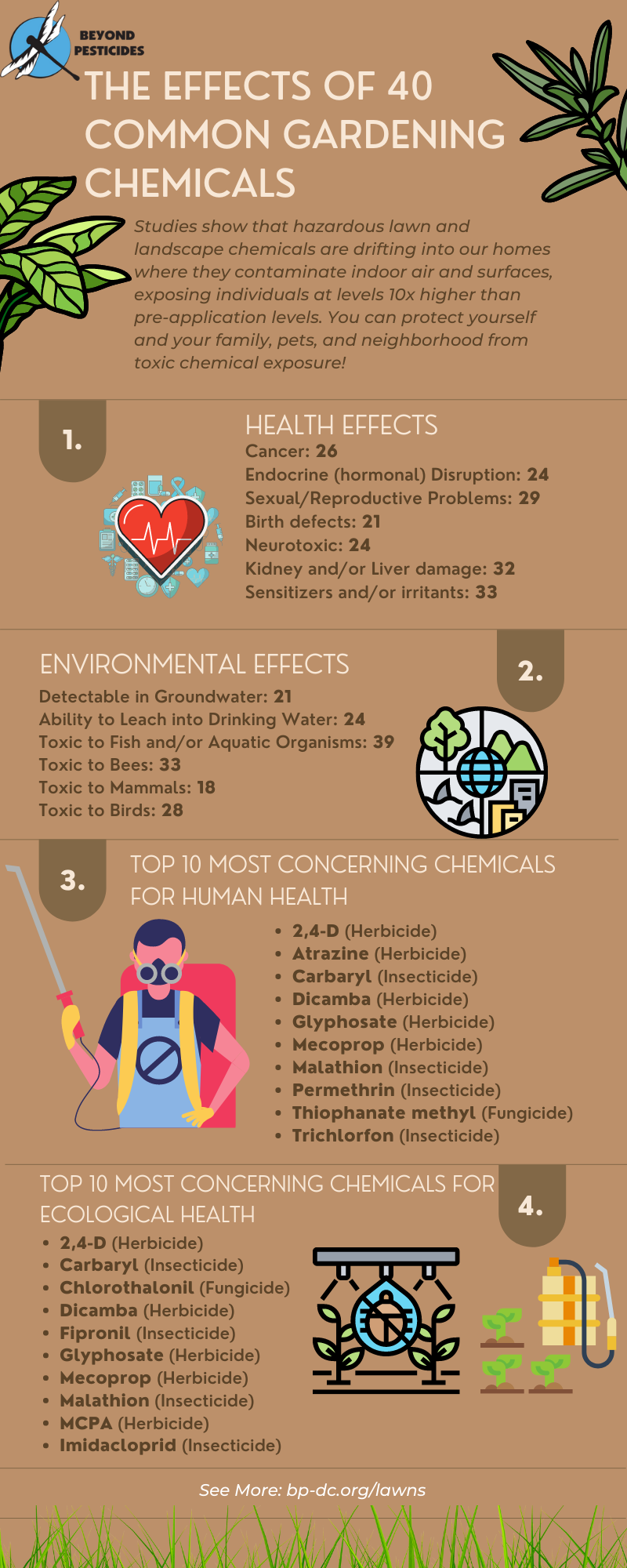

.png) ecological effects linked to pesticides. The underlying analysis supporting the adverse health and environmental effects identified in the factsheets are based on toxicity determinations in government reviews and university studies and databases.

ecological effects linked to pesticides. The underlying analysis supporting the adverse health and environmental effects identified in the factsheets are based on toxicity determinations in government reviews and university studies and databases.