16

Jun

Study Highlights Important Role Field Margins Play in Insect Conservation and Pest Management

(Beyond Pesticides, June 16, 2021) Uncultivated field margins contain almost twice as many beneficial insects as cropped areas around farm fields, according to research published this week in the Journal of Insect Science. The study finds that these predators and parasitoids overwinter in diverse vegetation, and can provide farmers an important jump start on spring pest problems. “A benefit of understanding overwintering is that those arthropods that emerge in the spring may be more inclined to feed on pests when pest populations are low,” said Scott Clem, PhD, coauthor of the study. “And so, they may be more likely to nip pest populations in the bud before the pest problem becomes a big deal.”

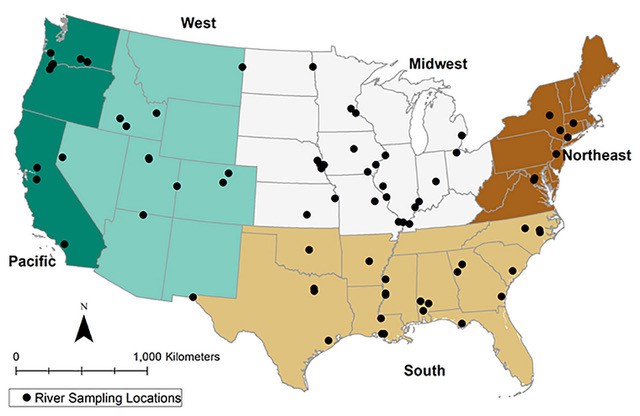

The study focused on five organic farms, as conventional chemically sprayed fields are not conducive to a thriving overwintering insect population. The farms, all located in the Midwest, each had 10 emergence tents set up both in the middle of the field and around field edges. Emergence tents capture insects that have spent their winter in soil and prevent predatory insects from escaping scientific analysis. After the tents were set up in mid-March 2018, samples were taken in late March, mid-April, and at the end of April.

In total, researchers collected 4,226 insects they considered beneficial, accounting for 95 species of parasitoids and pest predators. ¬†Arthropods collected along field boarders contained two times the diversity and abundance as emergence tents placed within crop fields. The divide between cultivated and uncultivated areas held for four of the farms. On one farm, the field boarder contained mostly grasses with few broadleaf plants and flowers and had been mowed short the previous fall. These field margins were much less diverse than those where farmers had planted wildflower seeds along the edges. ¬†“We were able to determine that these field edges are important for maintaining natural enemies of pest species in the landscape,” said Dr. Clem. “And the quality of the field border is likely to benefit the arthropod communities that live there and enhance the services they provide.”

Previous studies have found myriad benefits from the decision to dedicate a portion of one’s cropland to habitat for pest predators and parasitoids. In addition to their ability to help control pests, there is also evidence that non-crop areas like hedgerows can be an effective barrier against spray drift, reduce soil erosion, and act as habitat corridors for forest plants in agricultural landscapes. However, the ability  for these areas to manage pest populations is dependent upon maintaining favorable conditions for predators to thrive. A 2016 study published in Environment International finds that systemic pesticides like the neonicotinoids can run off from farm fields and make their way into wildflowers along field margins. In this context, these areas become a source sink, as pest predators are drawn to this area but then killed off due to local contamination. In fact, there is evidence that foraging bumblebees would rather dodge traffic than agricultural chemicals.  A 2015 study published in the Journal of Insect Conservation finds two times more pollinators on plants in field margins facing roadways than those facing agricultural fields.

But even conventional chemical farms can begin to shift when land is dedicated to biodiversity. Two studies published in November 2020 bear this out. One study, published in Science Advances, finds that conserving plant diversity around one’s farm can result in much lower rates of pest pressure on plants. Similarly, a study from researchers at University California, Santa Barbara, finds that more diverse landscapes lower insecticide use, while less diverse cropping areas lead to much more intensive pesticide applications.

As co-author Alexandra Harmon-Threatt, PhD, of the present study notes, “This research supports the idea that these uncropped areas — whether you want to call them field borders, field margins or even ditches — are really beneficial for insects and other arthropods. Preserving some land that is not cultivated and not mowing your field edges might make a big difference for insect conservation, but it’s probably also making a difference in controlling pests in farm areas, which is also super-important for meeting our other goals of feeding a growing population.”

For more information on the benefits of field margins and how you can plant more diverse areas around your home in garden (and subsequently reduce your need for pest management!), see Managing Landscapes with Pollinators in Mind and Hedgerows for Biodiversity: Habitat is needed to protect pollinators, other beneficial organisms, and healthy ecosystems.  You can also visit the  BEE Protective Habitat Guide and Do-It-Yourself Biodiversity  for more ways in which you can foster pest resilience in your backyard and community.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: University of Illinois, Journal of Insect Conservation