(Beyond Pesticides, February 24, 2019) With more than 90% of total pesticide use deployed in agriculture, organic farming is the keystone solution to the myriad health, environmental, and biodiversity harms of pesticides. A transition to organic and regenerative farming practices â across which there is great overlap â is critical and a tall order, given the entrenched, chemically intensive practices that currently dominate in the U.S. and much of the world. A long-standing research effort by the storied Rodale Institute â the Farming Systems Trial, which began in 1981â is demonstrating that organic agriculture is not only a nontoxic solution, but also, an economically viable one that is critical to a sustainable future.

Through the Farming Systems Trial (FST), the Rodale Institute has collected data on crop yields, soil health, energy efficiency, nutrient density of drops, and water use and contamination in organic and conventional systems managed with different levels of tillage. Among the findings of the nearly 40-year research project are these:

- after a five-year transition period, organic yields are competitive with conventional yields

âą in drought years, organic yields are as much as 40% higher than conventional yields

- farm profits are 3â6 times higher for products from organically managed systems

- organic management systems use 45% less energy than conventional, and release 40% fewer carbon emissions into the atmosphere

- organic systems leach no toxic chemicals into waterways

- organic systems build, rather than deplete, organic matter in soil, improving soil health

The trial website page notes that âorganic matter and thus soil health in organic systems continuously increases over time. Soil health in conventional systems remains essentially unchanged.â (See a detailed report from FST at the 30-year project mark here, and a brochure on the project here.)

The Rodale profitability outcome comports with that of a 2018 study on regenerative farming, as compared with conventional, chemical farming. The Farming Systems Trial project conclusions also reinforce those of a 2017 United Nations report; a 2016 report from the International Panel of Experts on Sustainable Food Systems; and a University of California, Berkeley study in 2014. The benefits of organic agriculture were discussed nearly a decade ago in an article from the Rodale Institute, republished in Beyond Pesticidesâ journal, Pesticides and You.

Begun in 1980 by founder Robert Rodale and created to yield practical data for farmers wanting to transition from conventional to organic practices, the FST is now significantly expanded from its early days. At the main Rodale campus in Kutztown, Pennsylvania, the trial occupies 12 acres, with 72 distinct plots. It is divided into three overarching management systems: Conventional Synthetic, Organic Manure, and Organic Legume. Each systemâs area is then divided into those utilizing tillage and, for the organic plots, reduced (alternate-year) tillage practices.

The practices employed under each of the three systems are described on the Rodale FST website: âConventional Synthetic represents a typical U.S. grain farm. It relies on synthetic nitrogen for fertility, and weeds are controlled by synthetic herbicides selected by and applied at rates recommended by Penn State University Cooperative Extension. . . . Organic Manure represents an organic dairy or beef operation. It features a long rotation of annual feed grain crops and perennial forage crops. Fertility is provided by leguminous cover crops and periodic applications of composted manure. A diverse crop rotation is the primary line of defense against pests. . . . Organic Legume represents an organic cash grain system [in part because it represents the 70% of U.S.-grown crops that are grains]. It features a mid-length rotation consisting of annual grain crops and cover crops. The systemâs sole source of fertility is leguminous cover crops and crop rotation provides the primary line of defense against pests.â

FTS is designed to be a long-term study that can capture episodic events, such as drought, longer-term weather effects, and changes in soil biology over time, as well as current management practices. The FTS looks to mimic standard agricultural approaches, so in 2008, genetically engineered (GE) crops and no-till practices were introduced to some conventional plots.

Once upon a time all agriculture was organic, but with the rise of chemical management in the mid-20th century, organic growing all but disappeared, but for intrepid âback to natureâ growers. Since the 1970s, and especially since the early 1990s, organic farming has steadily grown alongside Americansâ awareness of the health and environmental harms that conventional, chemically intensive agriculture imposes. An additional, but underreported, aspect of pesticide use is its relative inefficacy in some instances. Some pesticides just do not work all that well. In addition, as Beyond Pesticides wrote in 2019, âpesticidesâ actual utility is both inflated and severely limited, given the issue of resistance.â

Whatever chemical compound may work â for a given pest, on a given crop â may not work a year, or two, or three years hence, because pests (whether insects or weeds) will ultimately develop resistance to any substance to which they are repeatedly exposed. For example, when a target weed develops resistance to an herbicide, conventional agriculture responds â thanks to the chemical industry and its aggressive marketing and near hegemony on some seeds, such as soybeans â by using yet another herbicide, or doubling down with paired herbicides, or rolling out an herbicide-plus-GE-seed combination to try to stave off the pest. This âresistance and responseâ dynamic is a unidirectional progression along an increasingly poisonous and unsustainable path.

Beyond Pesticides wrote, in 2019, âChemical interventions to âcontrolâ pests of any sort, beyond all the potential toxicity issues, fundamentally cause imbalances in micro and macro ecological systems. . . . Fraught as it is with negative impacts on human and environmental health, including the mounting resistance issues, chemically intensive agriculture should be understood as a sign of the ineffectiveness of conventional, chemical approaches to pest control.â

Organic agriculture represents a range of management approaches; the most-codified and well-known signal of adherence to organic protocols is âCertified Organic,â a USDA label backed by a certification system that verifies that producers or processing facilities are in compliance with the National Organic Standards. Broadly, those rules say that certified organic food âmust be produced without the use of conventional pesticides, petroleum- or sewage-based fertilizers, herbicides, genetic engineering, antibiotics, growth hormones or irradiation. Certified organic farms must also adhere to certain animal health and welfare standards, not treat land with any prohibited substances for at least three years prior to harvest.â

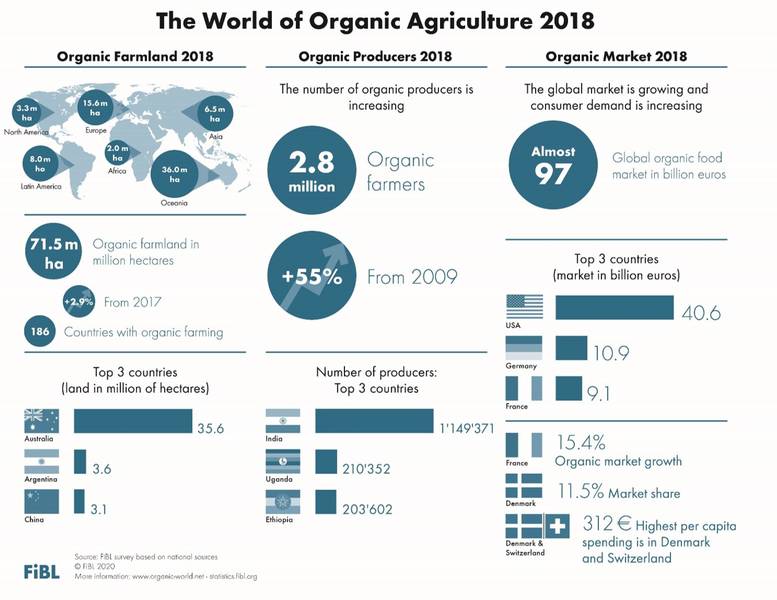

According to the most recent data from the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Service, the U.S. had more than 14,000 organic farms in 2016 â a 56% increase from 2011. Approximately 1% of the 911 million total U.S. acres of farmland is managed organically, which means that the task of conversion to organic and regenerative agriculture is significant. States with the greatest organic acreage in 2016 were California (by a wide margin, representing 21% of all U.S. certified organic farmland), followed by Montana, New York, and Wisconsin. California also led in the number of organic farms, with New York, Wisconsin, Maine, Iowa, and Pennsylvania also registering high on that list. Proportional to total farmland area, Vermont, California, Maine, and New York had the largest shares of certified organic acreage. Except for those states, the U.S. lags far behind some countries that have achieved more than 10% of farmland managed organically: Australia boasts the largest land area devoted to organic production, followed by Argentina and China.

Growth in the number of organic producers, organic acreage, and organic sales has responded to public demand for clean and healthful food. According to Bloomberg, Organic Trade Association Executive Director Laura Batcha said in 2019 that âyoung families are among the drivers in the organic market as they seek to avoid residues of chemicals, antibiotics, and hormones on food.â The Pew Research Center reported, âIn 2015, the Organic Trade Association estimated U.S. organic retail sales at $43 billion, representing double-digit growth in most years since 2000.â U.S. farm and ranch commodity sales rose by 23% from 2015 to 2016 alone. This level of demand bodes well for the momentum of organic.

The higher prices that organic products enjoy in the marketplace are no doubt one reason for Rodaleâs result â âfarm profits are 3â6 times higher for products from organically managed systems.â Higher profitability for farmers is certainly a strong âsellingâ point for conversion to organic, and can represent a bulwark against the stressors farmers are experiencing, including consolidation, âgrayingâ of farmers, development pressures, rising input costs, and insufficient generational transfer of land. Stressors on agriculture are even more pronounced currently, given the Trump administration tariffs that are negatively affecting U.S. farms.

Increased farmgate prices for organics, which are good for producers, can also be a strain on consumers who cannot afford organics at current pricing. Beyond the purchasing experience of the individual consumer, the simple differential between retail organic and non-organic prices does not tell the whole, systemic story. As Beyond Pesticides wrote about back in 2011, the accounting of the cost of conventional food production does not include the cost of the many externalized, negative health and environmental outcomes related to that production. âSome researchers calculate the adverse impacts to health and the environment to be as much as $16.9 billion a year [which is no doubt higher in 2020]. We still pay these costs, just not at the grocery checkout counter. Instead, we see these costs in the form of higher taxes and medical bills, and decreased quality of life due to environmental pollution.â

Organic production all but eliminates these externalized costs, making organic food â in the aggregate â far more affordable. Too, the âscalingâ phenomenon will work in agriculture as it does elsewhere: as more acres are put into organic production, and supply lines and the marketplace retool and scale up to accommodate consumer, producer, and processor needs, prices can be expected to shift downward somewhat in the longer term. As with all economic transitions, there is an uncomfortable âbetween paradigmsâ period. But as in other realms, a âjust transitionâ to organic, to protect agricultural workers and low-income consumers, is another important aspect of agricultural justice, and should be an important goal that is supported by appropriate federal and state policies.

Organic agricultural practices, which reject the use of harmful pesticides, are capable of the benefits the Rodale Institute Farming Systems Trial is demonstrating. Such practices protect human and animal health, and support functional ecosystems and biodiversity. Widespread adoption of organic and regenerative agriculture can also lift human agro-activity out of its current chemical dead-end. The public has an important role to play in this transition: learn more about organic agriculture, advocate for it, and âvoteâ for organics by creating market demand for organic food.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Sources: https://rodaleinstitute.org/science/farming-systems-trial/ and https://www.cornucopia.org/2015/07/30-year-old-trial-finds-organic-farming-outperforms-conventional-agriculture/?fbclid=IwAR3RDJsezWtb9xQ8QeMjtMzA_iYGDTWKTNDwovK7Wj8PW4bHvwojEycQWpg

(Beyond Pesticides, March 23, 2020)Â Ignoring science to side with Monsanto/Bayer, EPA has repeatedly failed to assess glyphosateâs impacts on public health and endangered species.

(Beyond Pesticides, March 23, 2020)Â Ignoring science to side with Monsanto/Bayer, EPA has repeatedly failed to assess glyphosateâs impacts on public health and endangered species.

(Beyond Pesticides, March 19, 2020) As communities across the U.S. brace for an unimaginable health crisis and difficult economic times in the wake of COVID-19, the Beyond Pesticides Hawaiâi team has linked arms with Mauiâs small farms and community organizations to make sure local farms have the support they need to feed communities and stay in business. The virus is causing shutdowns of everything from farmers markets to restaurants, but community organizers in Maui are making an effort to transform COVID-19 related challenges into a spring board for long-term increase in locally produced, organic foodâa sorely needed commodity in Hawaiâi.Â

(Beyond Pesticides, March 19, 2020) As communities across the U.S. brace for an unimaginable health crisis and difficult economic times in the wake of COVID-19, the Beyond Pesticides Hawaiâi team has linked arms with Mauiâs small farms and community organizations to make sure local farms have the support they need to feed communities and stay in business. The virus is causing shutdowns of everything from farmers markets to restaurants, but community organizers in Maui are making an effort to transform COVID-19 related challenges into a spring board for long-term increase in locally produced, organic foodâa sorely needed commodity in Hawaiâi.

(Beyond Pesticides, March 12, 2020) Farmworkers walked out of an orchard in Sunnyside, Washington on Friday, March 6 to demand improved working conditions. Over a dozen individuals cited unacceptable issues, such as toxic pesticide exposure, unfair wages, and lack of paid breaks. Their employer, Evans Fruit, owns and farms over 8,000 acres in the state. These workers represent the ongoing fight against injustice perpetuated by the chemical-intensive agriculture industry.

(Beyond Pesticides, March 12, 2020) Farmworkers walked out of an orchard in Sunnyside, Washington on Friday, March 6 to demand improved working conditions. Over a dozen individuals cited unacceptable issues, such as toxic pesticide exposure, unfair wages, and lack of paid breaks. Their employer, Evans Fruit, owns and farms over 8,000 acres in the state. These workers represent the ongoing fight against injustice perpetuated by the chemical-intensive agriculture industry.

UPDATE: The same day Beyond Pesticides published this piece, Gulbrandsen Chemicals announced it would drop its effort to produce pentachlorophenol in Orangeburg, SC, according to

UPDATE: The same day Beyond Pesticides published this piece, Gulbrandsen Chemicals announced it would drop its effort to produce pentachlorophenol in Orangeburg, SC, according to

(Beyond Pesticides, March 6, 2020) Scientists from Imperial College London have just published their recent

(Beyond Pesticides, March 6, 2020) Scientists from Imperial College London have just published their recent

(Beyond Pesticides, March 3, 2020) Pregnant mothers living in areas where carcinogenic pesticides have been used are at increased risk of their child developing an acute form of leukemia, according to research published last month in the

(Beyond Pesticides, March 3, 2020) Pregnant mothers living in areas where carcinogenic pesticides have been used are at increased risk of their child developing an acute form of leukemia, according to research published last month in the