20

Aug

Arctic Glaciers Entrap Pesticides and Other Environmental Pollutants from Global Drift and Release Hazardous Chemicals as They Melt from Global Warming

(Beyond Pesticides, August 20, 2020) Persistent organic pollutants (POPs), including banned and current-use pesticides are present in snow and ice on top of Arctic glaciers, according to the study, âAtmospheric Deposition of Organochlorine Pesticides and Industrial Compounds to Seasonal Surface Snow at Four Glacier Sites on Svalbard, 2013â2014,â published in Environmental Science & Technology. Past research finds that air contaminated with these environmentally bioaccumulative, toxic chemicals drift toward the poles, becoming entrapped in ice under the accumulating snowfall. As the global climate continues to rise and the climate crisis worsens, studies like this become significant, as glaciers encapsulating these toxic chemicals are melting. Upon melting, some chemicals can volatize back into the atmosphere releasing toxicants into air and aquatic systems, with the ensuing consequences. Although this research demonstrates that specific computer programs can track the trajectory of chemically contaminated air parcels with practical precision, it falls to global leaders to curtail the continued manufacturing of these chemical pollutants. [For related pieces, see Silent Snow: The unimaginable impact of toxic chemical use and DDT in Glacial Melt Puts Alaskan Communities at Risk.]

Countless scientists consider Arctic environments to be âpristine,â void of direct chemical inputs from pesticides and other POPs. However, the Arctic has become a sink for these toxic chemicals, as studies find evidence that airborne Arctic POPs concentrations are comparable to that of industrialized regions like the U.S., Europe, and Asia. Additional investigations find the presence of POPs in soil and ice samples taken from Arctic regions. The problem is escalating, despite the 2001 Stockholm Conventionâa global treaty to eliminate POPsâ signed by 183 countries and the European Union, but not the United States. While various POPs on the Stockholm Convention annex lists are no longer manufactured or utilized, POPs still mobilize and accumulate in regions void of industrial or agricultural activities, like glacier tops and remote territories. As the Convention states, âGiven their long-range transport, no one government acting alone can protect its citizens or its environment from POPs.â Although a plethora of studies document chemical pollution in the Arctic, researchers note that, â[T]his study represents the first attempt to understand how atmospheric pollutants are captured by snow and deposited at high-elevation glacial sites.â

This study quantifies POPs accumulation deposited on Arctic snow over one winter using four glaciers of various altitudes (Holtedahlfonna, Kongsvegen, Lomonosovfonna, and Austfonna) across Svalbard (a Norwegian archipelago). While the presence of POPs in Arctic air is well-known, much less is understood about atmospheric deposition. To identify what chemicals are present, researchers collected and analyzed 12 snow samples from each glacier site, surveying for 36 pesticides and seven industrial chemicals with Gas Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (GCâhigh-resolution MS). To assess contamination variability between glacial sites, researchers used a Hybrid Single-Particle Lagrangian Integrated Trajectory (HYSPLIT) model to evaluate long-range atmospheric transport by measuring how frequently POPs-contaminated air masses came from source areas to sampling sites.

All seven industrial chemicals and thirteen pesticides are detectable at all glacier sampling sites, with the total fluctuation of pesticide concentrations greater than industrial chemicals at all sites, according to the study. The seven industrial chemicals include hexachlorobutadiene, 1,2,3,4-tetrachlorobenzene, 1,2,4,5-T4CB, pentachlorobenzene, pentachloroanisole, 3,4,5,6-tetrachlorodimethoxybenene, and hexachlorobenzene. The thirteen pesticides include heptachlor, heptachlor epoxide B, aldrin, α-and Îł-hexachlorocyclohexane (HCH), chlorpyrifos, trans- and cis-chlordane, 4,4âČ-DDE, dieldrin, dacthal (DCPA), trans-nonachlor, and α-endosulfan. Chlorpyrifos, dieldrin, and trans-chlordane dominate most Arctic areas, accounting for at least 50% of the total pesticide concentrations at each sample site. As for air mass variability among glacial sites, Austfonna has the most frequent long-distance transport of air masses, suggesting that air masses circulate in this area for a majority of the time during winter from sources other than the local sampling sites.

The Arctic is highly susceptible to global pollution, as warmer air contaminated with industrial and agricultural chemicals from manufacturing regions move poleward toward cooler air. Pollutants, like POPs, condense on snowflakes, high in the atmosphere, and deposit onto the Arctic surface. Although deposition of these chemicals via long-range atmospheric transport and condensation are significant contributors to Arctic contamination, the chemical properties allowing these substances to persist in the environment so long are concerning. Some of these long-lived chemicals include regionally banned pesticides like DDT, heptachlor, and lindane, which are highly toxic to humans and animals, causing a range of adverse effects, from respiratory issues, nervous system disorders, birth deformities, to various common and uncommon cancers. Although some but not all manufacturing and use of specific POPs have declined in the U.S., POPs remain a global issue, as much of the developing world still reports usage. Continued use of POPs will result in an increased probability of long-range transport of these chemicals for deposition on Arctic glacier tops via precipitation. According to Brettania Walker, PhD, Toxics Officer at World Wildlife Fund’s Arctic Program, “Not only is chemical contamination increasing in the Arctic, but also modern chemicals are now appearing in many arctic species alongside older chemicals, some of them banned for over [30] years.”

As the concentration of POPs increases in the Arctic, the climate crisis adds another level of concern, especially regarding passive pesticide exposure from snowmelt. Pesticide contamination is already an issue in the U.S., as results of the United States Geological Surveyâs (USGS) and National Water-Quality Assessment (NAWQA) studies show that pesticides and their degradants are present in U.S. streams and widespread in groundwater throughout the country. Furthermore, a recent study shows Chicago-based black women consuming more glasses of tap water per day have residues of the DDT metabolite (DDEâ) in their system. However, the glacial melting caused by the climate crisis will only add to water source contamination, as the release of volatile POPs will enter waterways at the same concentration levels as before ice entrapment, even after several decades.

Many POPs are not soluble in water, but bioaccumulate in the fatty tissue of many Arctic species, such as polar bears, seals, whale, and some fatty fish like salmon, herring, and catfish. Arctic penguinsâ blubber contains levels of DDT similar to when the product was initially banned more than 30 years ago. Unfortunately, some indigenous tribes in Arctic regions rely on these very mammals and fish for sustenance, and ingesting these pollutants is inevitable, putting their health at risk. Higher bodily concentrations of POPs is evident in those who consume contaminated meat with associated health risks, including immune system disorder, increased susceptibility to disease, central nervous system disorders, learning disabilities among children, reproductive issue, and cancer. Studies find that adults and children who regularly consume fish from contaminated streams are at increased risk of cancer from dietary and cumulative exposure, in many cases above EPA thresholds.

As global warming progresses and the melting glaciers release more POPs into waterways, exposure concerns will increase significantly, especially for children who are more vulnerable to toxic effects of chemical exposure. To mitigate the risks associated with chemical exposure from toxic pesticides, advocates say that the manufacturing and use of pesticides must be addressed first and foremost. Recently, agrochemicals like pesticides and fertilizers overtook the fossil fuel industry as the leading contributor of environmental sulfur emissions. If pesticide use and manufacturing are amplifying the impacts of the climate crisis, advocates argue that it is essential to incite change at the point source via enhanced pesticide policy and regulation that eliminates use.

Chlorpyrifos and dacthal are the two pesticides from the study that are in current use in the U.S., with chlorpyrifos being the more abundant of the two chemicals. In 2000, EPA negotiated to withdraw chlorpyrifos from most residential markets, due to the neurotoxic effects on children. However, uses in agriculture, on golf courses, and for public health mosquito management continue. Human exposure to this chemical can induce endocrine disruption, reproductive dysfunction, fetal defects, neurotoxic damage, and kidney/liver damage. While the U.S. manufacturer, Corteva (formerly DowDupont) decided to stop chlorpyrifos production at the end of 2020, it is maintaining its registration with EPA as generic manufacturers will  continue production. Three statesâHawaii, California, New Yorkâand the European Union have adopted some form of phase out or restriction of its agricultural uses. After passing legislation in Maryland to restrict chlorpyrifos use, the bill is awaiting the Governorâs signature. Dacthal, on the other hand, remains in production and has possible links to skin and eye irritation, liver/kidney damage, and cancer.

As global warming associated with the climate crisis continues to melt glaciers, banned and current-use pesticides pose a risk to human and animal health upon release into the atmosphere and waterways. Lack of adequate persistent pesticide regulations highlights the need for better policies surrounding pesticide use, especially when a toxic pesticide is banned for use in the U.S., but not for production and export to other countries.Â

A switch from chemical-intensive agriculture to regenerative organic agriculture can significantly reduce the threat of the climate crisis by eliminating toxic, petroleum-based pesticide use, building soil health, and sequestering carbon. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) finds that agriculture, forestry, and other land use contributes about 23% of total net anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases, while organic production reduces greenhouse gas emissions and sequesters carbon in the soil. Learn more about how it is possible to sequester more than 100% of current annual CO2 emissions by switching to organic management practices by reading Regenerative Organic Agriculture and Climate Change: A Down-to-Earth Solution to Global Warming. For more information about organic food production, visit Beyond Pesticides Keep Organic Strong webpage. Learn more about the adverse health and environmental effects chemical-intensive farming poses for various crops and how eating organic produce reduces pesticide exposure.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source(s): Earth Institute | Columbia University, Â Environmental Science & Technology

(Beyond Pesticides, August 19, 2020) Stranded dolphins and whales along the United States Eastern Seaboard contain herbicides, disinfectants, plastics, and heavy metals, research published in

(Beyond Pesticides, August 19, 2020) Stranded dolphins and whales along the United States Eastern Seaboard contain herbicides, disinfectants, plastics, and heavy metals, research published in  (Beyond Pesticides, August 18, 2020) Ongoing declines in bird population and diversity are being accelerated by the use of

(Beyond Pesticides, August 18, 2020) Ongoing declines in bird population and diversity are being accelerated by the use of  (Beyond Pesticides, August 17, 2020)Â Once numbering in the millions, barely 29,000 western monarch butterflies were found in California at last count. Pesticides pack a one-two punch against monarchs. Insecticidesâparticularly neonicotinoidsâpoison the caterpillars and butterflies as they feed. Glyphosateâthe active ingredient in Bayer-Monsanto’s RoundupÂź â is wiping out milkweed, the only food source for monarch caterpillars. This has contributed to monarchs’ 90% decline in the past 20 years alone. They could vanish within our lifetimes.

(Beyond Pesticides, August 17, 2020)Â Once numbering in the millions, barely 29,000 western monarch butterflies were found in California at last count. Pesticides pack a one-two punch against monarchs. Insecticidesâparticularly neonicotinoidsâpoison the caterpillars and butterflies as they feed. Glyphosateâthe active ingredient in Bayer-Monsanto’s RoundupÂź â is wiping out milkweed, the only food source for monarch caterpillars. This has contributed to monarchs’ 90% decline in the past 20 years alone. They could vanish within our lifetimes. (Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2020)Â Levels of the notorious herbicide compound

(Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2020)Â Levels of the notorious herbicide compound  (Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2020) An alarming new scientific report finds that excessive, indiscriminate disinfectant use against COVID-19 puts wildlife health at risk, especially in urban settings. The analysis, published in the journalÂ

(Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2020) An alarming new scientific report finds that excessive, indiscriminate disinfectant use against COVID-19 puts wildlife health at risk, especially in urban settings. The analysis, published in the journal  (Beyond Pesticides, August 12, 2020) The herbicide atrazine can interfere with the health and reproduction of marsupials (including kangaroos and opossums)

(Beyond Pesticides, August 12, 2020) The herbicide atrazine can interfere with the health and reproduction of marsupials (including kangaroos and opossums)

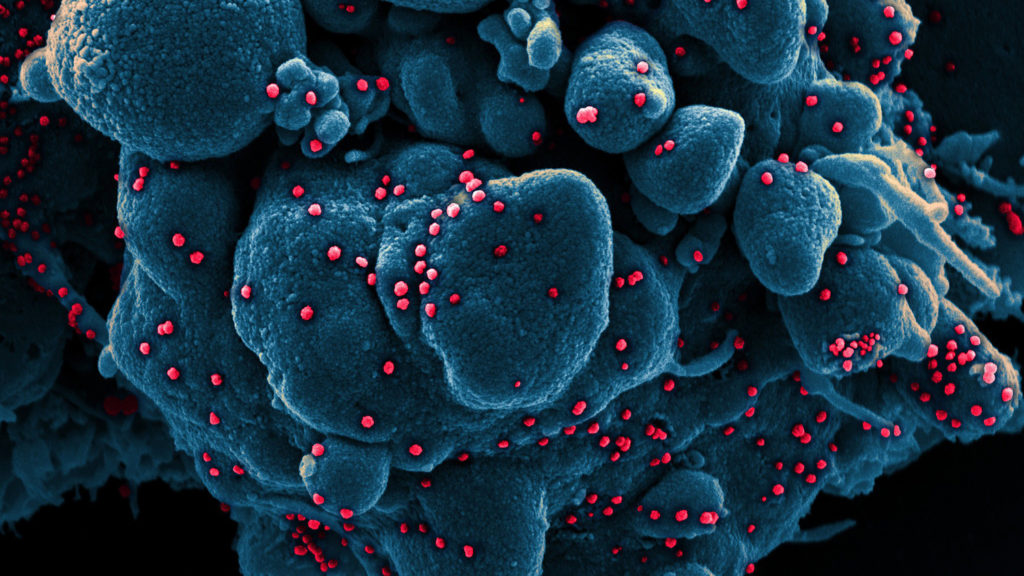

(Beyond Pesticides, August 10, 2020) As parents, educators, and administrators decide whether to open schools with in-person teaching, there are escalating concerns about the ability of schools to put in place the programs necessary to protect the health of students, staff, and their families from coronavirus (COVID-19). A key part of most school reopening plans is the fogging or misting of classrooms with toxic disinfectants, raising questions about safe and effective disinfection and sanitizing practices, in addition to social practices that public health officials have advised, to prevent transmission of the virus.

(Beyond Pesticides, August 10, 2020) As parents, educators, and administrators decide whether to open schools with in-person teaching, there are escalating concerns about the ability of schools to put in place the programs necessary to protect the health of students, staff, and their families from coronavirus (COVID-19). A key part of most school reopening plans is the fogging or misting of classrooms with toxic disinfectants, raising questions about safe and effective disinfection and sanitizing practices, in addition to social practices that public health officials have advised, to prevent transmission of the virus. (Beyond Pesticides, August 7, 2020) Research out of the Silent Spring Institute

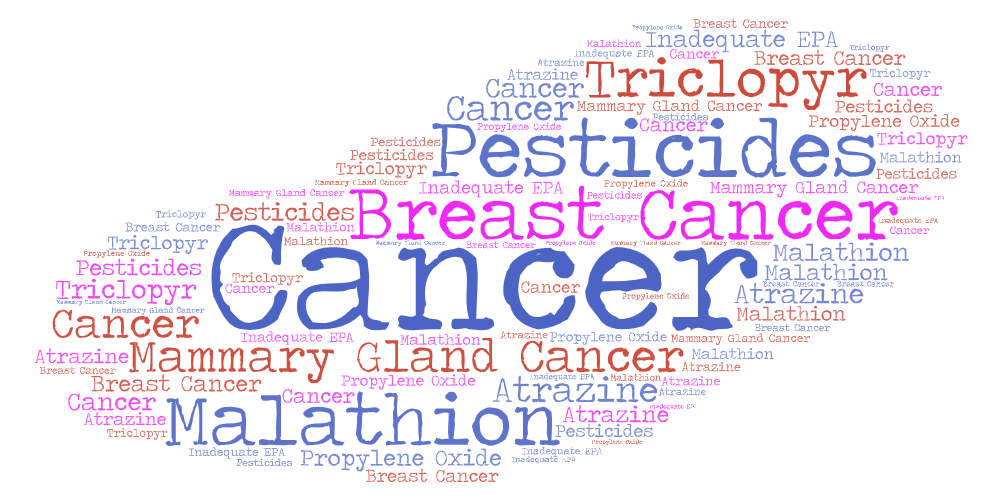

(Beyond Pesticides, August 7, 2020) Research out of the Silent Spring Institute  (Beyond Pesticides, August 6, 2020) New research finds that a decline in wild pollinator abundance, notably wild bees, limits crop yields in the U.S., according to the study, â

(Beyond Pesticides, August 6, 2020) New research finds that a decline in wild pollinator abundance, notably wild bees, limits crop yields in the U.S., according to the study, â (Beyond Pesticides, August 5, 2020) Regions of Australia that use a highly toxic rodenticide are home to larger dingoes than areas where the pesticide is not used, according to research published in the

(Beyond Pesticides, August 5, 2020) Regions of Australia that use a highly toxic rodenticide are home to larger dingoes than areas where the pesticide is not used, according to research published in the  (Beyond Pesticides, August 4, 2020) Last month Massachusetts lawmakers finalized, and the Governor subsequently signed,

(Beyond Pesticides, August 4, 2020) Last month Massachusetts lawmakers finalized, and the Governor subsequently signed,  (Beyond Pesticides, August 3, 2020)Â The effects of pesticide use are important, yet ignored, factors affecting people of color (POC) who face elevated risk from Covid-19 as essential workers, as family members of those workers, and because of the

(Beyond Pesticides, August 3, 2020)Â The effects of pesticide use are important, yet ignored, factors affecting people of color (POC) who face elevated risk from Covid-19 as essential workers, as family members of those workers, and because of the  (Beyond Pesticides, July 31, 2020)Â On July 22, the New York State Legislature passed

(Beyond Pesticides, July 31, 2020)Â On July 22, the New York State Legislature passed  (Beyond Pesticides, July 30, 2020) Simultaneous exposure to pesticides and noise from agricultural machinery increases farmworkers, risk of hearing loss, according to the study, â

(Beyond Pesticides, July 30, 2020) Simultaneous exposure to pesticides and noise from agricultural machinery increases farmworkers, risk of hearing loss, according to the study, â (Beyond Pesticides, July 29, 2020) Farmworkers and landscapers are deemed essential employees during the coronavirus outbreak, but without mandated safety protocols or government assistance, have experienced an explosion in Covid-19 cases. Workers in these industries are primarily Latinx people of color, many of whom are undocumented. According to a

(Beyond Pesticides, July 29, 2020) Farmworkers and landscapers are deemed essential employees during the coronavirus outbreak, but without mandated safety protocols or government assistance, have experienced an explosion in Covid-19 cases. Workers in these industries are primarily Latinx people of color, many of whom are undocumented. According to a  (Beyond Pesticides, July 28, 2020) With honey bees around the world under threat from toxic pesticide use, researchers are investigating a new way to track environmental contaminants in bee hives. This new product, APIStrip (Adsorb Pesticide In-hive Strip), can be placed into bee hives and act as a passive sampler for pesticide pollution. Honey bees are sentinel species for environmental pollutants, and this new technology could provide a helpful way not only for beekeepers to pinpoint problems with their colonies, but also track ambient levels of pesticide pollution in a community.

(Beyond Pesticides, July 28, 2020) With honey bees around the world under threat from toxic pesticide use, researchers are investigating a new way to track environmental contaminants in bee hives. This new product, APIStrip (Adsorb Pesticide In-hive Strip), can be placed into bee hives and act as a passive sampler for pesticide pollution. Honey bees are sentinel species for environmental pollutants, and this new technology could provide a helpful way not only for beekeepers to pinpoint problems with their colonies, but also track ambient levels of pesticide pollution in a community. (Beyond Pesticides, July 27, 2020)

(Beyond Pesticides, July 27, 2020)  (Beyond Pesticides, July 24, 2020)Â As the novel coronavirus pandemic has heightened awareness of infectious diseases, there is increased attention to connections between environmental concerns and such diseases, including factors that may exacerbate their transmission.

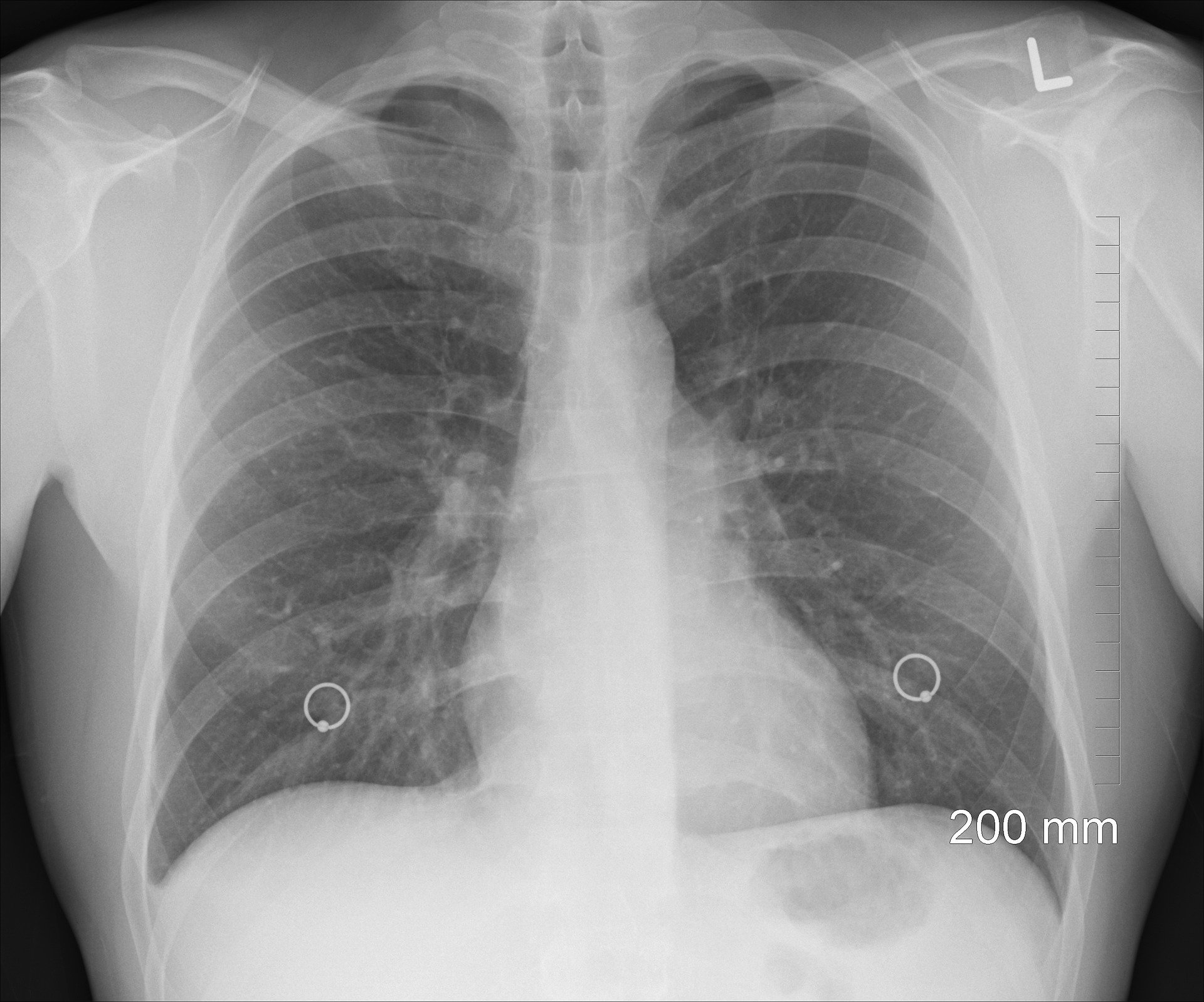

(Beyond Pesticides, July 24, 2020)Â As the novel coronavirus pandemic has heightened awareness of infectious diseases, there is increased attention to connections between environmental concerns and such diseases, including factors that may exacerbate their transmission.  (Beyond Pesticides, July 23, 2020) Chronic pesticide use, and subsequent exposure, elevate a personâs risk of developing lung cancer, according to a study published inÂ

(Beyond Pesticides, July 23, 2020) Chronic pesticide use, and subsequent exposure, elevate a personâs risk of developing lung cancer, according to a study published in  (Beyond Pesticides, June 22, 2020) In the latest issue of

(Beyond Pesticides, June 22, 2020) In the latest issue of