11

Oct

In Response to a Lawsuit, EPA Proposes Review Process for Evaluating the Effects of Multiple Pesticide Ingredients on Nontarget Organisms

(Beyond Pesticides, October 11, 2019)Â The Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is seeking public comment on a document that describes an âinterim processâ being used to assess potential synergistic effects of admixtures of pesticide active ingredients on non-target organisms. This interim risk assessment process was catalyzed in part by a 2015 lawsuit brought by a group of non-governmental organizations; that suit cited EPAâs failure to evaluate appropriately the impacts of a new herbicide, Enlist Duo, on non-target species, including some endangered species. EPAâs inattention to synergistic impacts on non-target species has long been a deficiency of EPAâs pesticide review and regulation and a focus for Beyond Pesticidesâ work to factor in uncertainties, or unknowns, in registering pesticides under a precautionary approach. Although EPA recognizes that pesticide exposures occur in combinations, it evaluates a very limited number of such interactions.

(Beyond Pesticides, October 11, 2019)Â The Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is seeking public comment on a document that describes an âinterim processâ being used to assess potential synergistic effects of admixtures of pesticide active ingredients on non-target organisms. This interim risk assessment process was catalyzed in part by a 2015 lawsuit brought by a group of non-governmental organizations; that suit cited EPAâs failure to evaluate appropriately the impacts of a new herbicide, Enlist Duo, on non-target species, including some endangered species. EPAâs inattention to synergistic impacts on non-target species has long been a deficiency of EPAâs pesticide review and regulation and a focus for Beyond Pesticidesâ work to factor in uncertainties, or unknowns, in registering pesticides under a precautionary approach. Although EPA recognizes that pesticide exposures occur in combinations, it evaluates a very limited number of such interactions.

Manufactured by Dow AgroSciences, Enlist Duo combines glyphosate and 2,4-D. Increasingly, manufacturers create and market such âtwoferâ products as responses to the burgeoning issue of plant resistance to individual pesticides. As insects, fungi, weeds, or other âpestsâ inevitably develop resistance to pesticide, herbicide, fungicide, or insecticide compounds, the efficacy of the chemical treatment obviously plummets. Manufacturer response is often either to find a new chemical, or to âdouble downâ with combined-ingredient products that may be effective until the next wave of resistance develops.

EPA acknowledged, during that 2015 litigation, which challenged EPA registration of Enlist Duo, that some patent applications for registered pesticide products claim that they provide so-called âsynergisticâ control of target species. The patent assertions about greater than additive (GTA) effects have âraised questions and concerns about the EPAâs current process for evaluating ecological risks of pesticide mixtures because some target pests are also members of taxonomic groups of nontarget organisms that EPA assesses.â Also in 2015, EPA asked the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit to âvacate its [2014] registration decision and remand the application for Enlist Duo for further study of these effects and any measures that might be needed to mitigate the risk to non-target organisms.â The court denied EPAâs request.

Of EPAâs call for public comment, the National Law Review notes that, âEPA typically registers pesticide products that are not intended to protect public health without any independent evaluation of efficacy data. Nevertheless, in general EPA may choose to evaluate pesticidal efficacy data; such circumstances in the past often involved cases where EPA was required to consider whether pesticide benefits are sufficient to outweigh identified risks. In the Enlist [Duo] case, EPA determined that it should do so where potential synergy in pesticidal efficacy is pertinent to evaluating ecological effects on non-target species. What EPA must decide now is how often efficacy data that has been deemed adequate by the Patent and Trademark Office to support a patent for a new pesticide mixture will have any material significance in the context of ecological risk assessment. . . . EPA has decided it is prudent to afford all stakeholders an opportunity to comment on whether EPA has been asking the right questions.â

Some background: an application for registration of a pesticide product must meet standards in order to be approved. EPA describes those: âApplicants are responsible for citing or generating all data necessary to meet data requirements specified by FIFRA [the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act, the federal law that created the basic system of pesticide regulation]. The standard for determining whether an application should be granted includes a finding that: (1) a product’s composition warrants the proposed claims for it; (2) the product’s labeling and other material required to be submitted complies with FIFRA; (3) the product will perform its intended function without causing unreasonable adverse effects on the environment; and (4) when used in accordance with widespread and commonly recognized practice, the product will not cause unreasonable adverse effects on the environment.â FIFRA defines âunreasonable adverse effectsâ as âany unreasonable risk to man or the environment, taking into account the economic, social, and environmental costs and benefits of the use of any pesticide.â

For new chemicals in EPAâs pesticide registration process â about which EPA has specific concerns about the potential for GTA effects â the OPP protocol proposes to ârequestâ that registrants: (1) review data from existent patent applications that assert GTA effects from active ingredient interactions; (2) compare data from those applications to EPA ecological risk assessment relevancy criteria; (3) report effects testing data from relevant patents; and (4) âanalyze the data to determine if observations of greater than additive effects in mixtures are statistically significant in the context of test variability.â EPA would then review all submitted information to decide whether it should be utilized in ecological risk assessment. Importantly, OPP would rely here on: (1) registrant-submitted data rather than independently secured data, and (2) registrantsâ compliance with the ârequests.â The Federal Register notice of the protocol document does at least indicate that EPA is âuncertain concerning the utility for risk assessment of the information used by manufacturers to support synergistic effects claims in pesticide patents.â

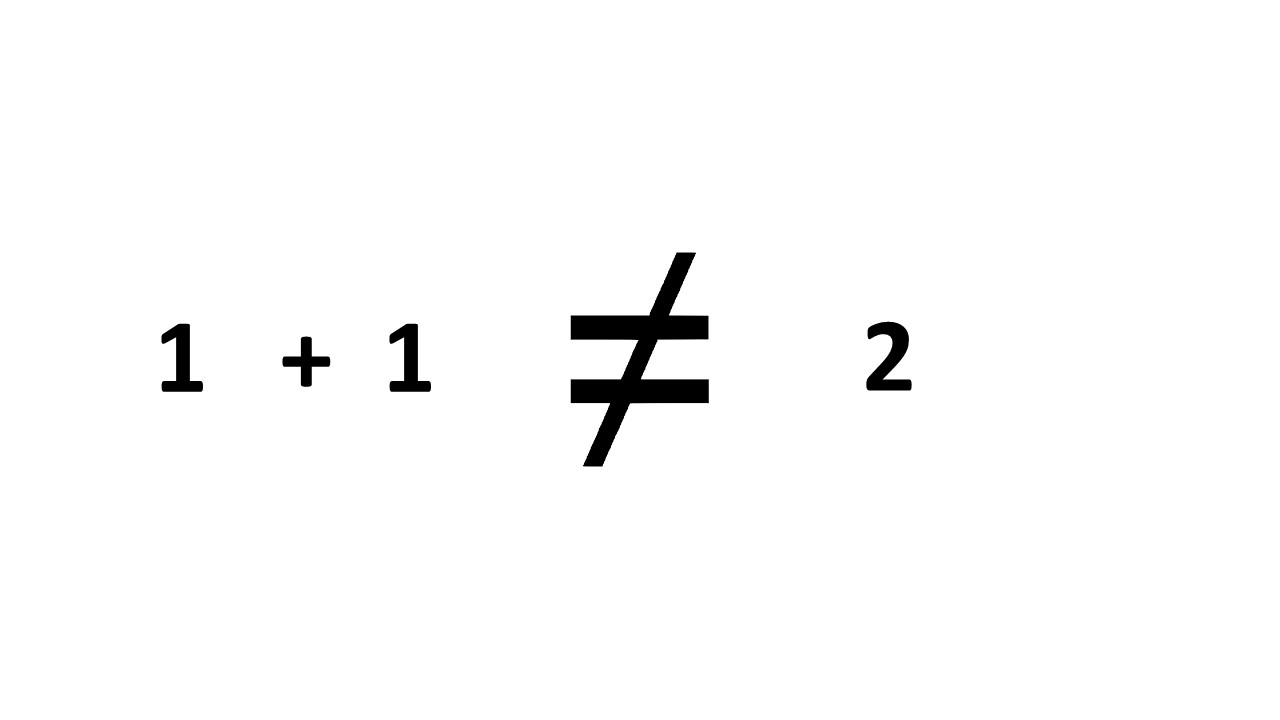

âSynergyâ in the pesticide context has two aspects: one is what these patent applications claim, which is some âgreater than the sum of its partsâ or âgreater than additiveâ impact on, e.g., weed suppression, by these herbicides with multiple active ingredients. The other aspect is the largely unexamined â by regulators â universe of threats that exposure to multiple pesticide ingredients poses to the environment and to nontarget plant and animal species.

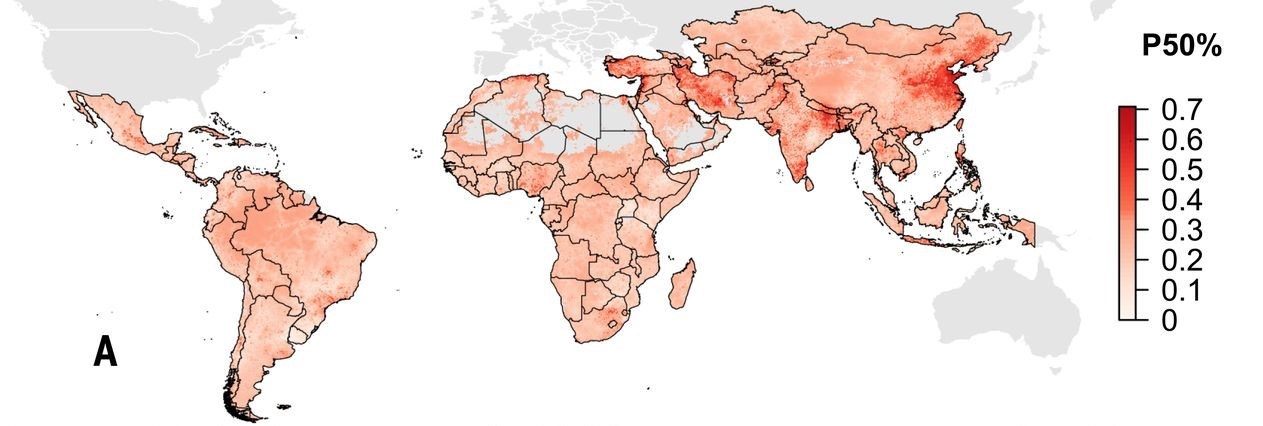

The OPP document, titled Process for Receiving and Evaluating Data Supporting Assertions of Greater Than Additive (GTA) Effects in Mixtures of Pesticide Active Ingredients and Associated Guidance for Registrants, sets out the process that OPPâs Environmental Fate and Ecological Effects Division is using in its attempts to evaluate synergistic risks. However, that process reviews only those admixtures whose makers assert that their efficacy on the target weed or pest is synergistic. OPPâs narrow focus ignores all the other potential synergistic impacts â effects that may arise when organisms, whether floral or faunal, are exposed to multiple active pesticide ingredients. Such âmixingâ may happen during industry formulation of a product, in an applicatorâs garage or barn, or at the organismic point of exposure via air, water, soil, and/or food.

OPPâs protocol is typical of EPAâs failure to consider risks related to all those other vectors for exposure to multiple pesticides. In a 2016 letter to EPA, Beyond Pesticides noted, for example, that although EPA had concluded that âthe combination of 2,4-D choline and glyphosate in Enlist Duo does not show any increased toxicity to plants,â it was unclear that EPA had evaluated synergistic risks to other, non-plant organisms (including humans), who would be exposed to this chemical mixture. Beyond Pesticides wrote, âIt does not appear that assessments, based on exposure to both glyphosate and 2,4-D choline, have been conducted to properly assess whether synergistic effects can occur in non-plant organisms.â Beyond Pesticides has advocated, in the face of EPAâs inattention synergistic impacts, that the EPA Office of the Inspector General â tasked with conducting âaudits and investigations of EPA to promote economy and efficiency, and to prevent and detect fraud, waste and abuseâ â investigate this critical failure.

Beyond Pesticides advocates robustly for a regulatory approach to pesticides that prohibits high-risk chemical practices, and rejects uses and exposures deemed acceptable under risk assessment calculations filled with uncertainty. Rather, the federal regulatory framework should focus on safer, effective alternatives, such as organic agriculture, which prohibits the vast majority of toxic chemicals.

Beyond Pesticides encourages public comment on the OPP risk assessment protocol. Such commentary could include the following points:

- Impacts of pesticides mixtures, which occur in in air, soil, water, and agricultural products, should be considered in all EPA registration decisions.

- Any decision that a pesticide does not cause unreasonable adverse effects (considering all the risks and benefits) requires EPA to determine whether a pesticide is effective. Thus, efficacy data should be required for all pesticides.

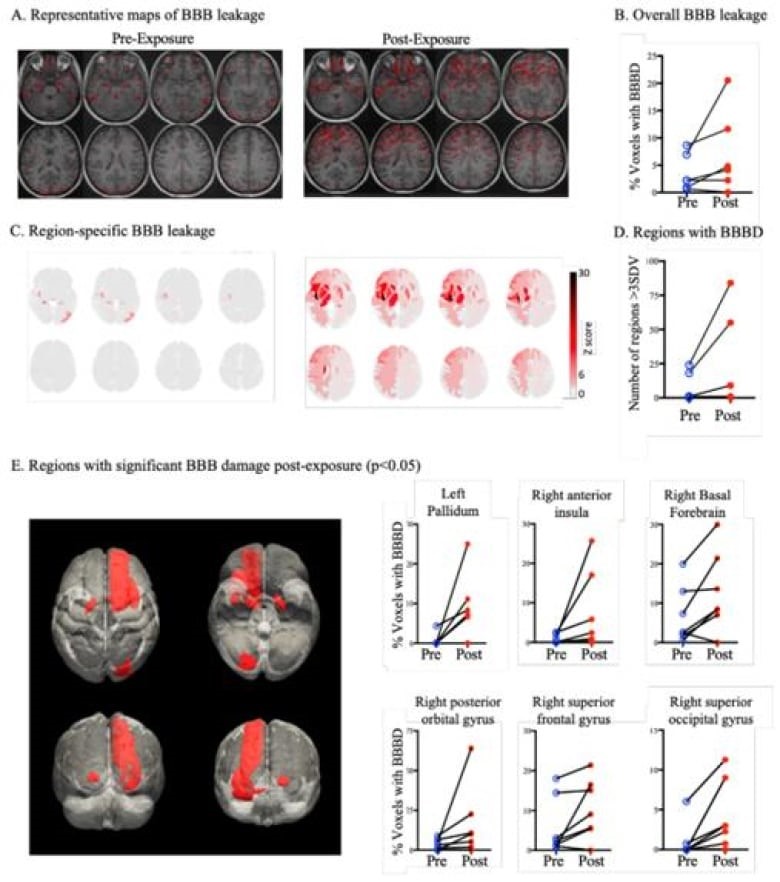

- Synergistic effects of pesticides may involve interactions with pharmaceuticals or naturally occurring biochemicals and processes in humans and other organisms.

- Synergistic effects may be mediated in the environment; for example, an herbicide may destroy habitat for an animal that is also being poisoned by an insecticide.

- EPA should investigate potential synergistic impacts of all pesticides.

Public comments on the proposed EPA policy can be contributed here until October 24 at 11:59pm EST. Please consider incorporating the bullet points above in your comments to EPA.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

(Beyond Pesticides, October 10, 2019) Mysterious vaping illnesses across the country could be related to pesticide exposure, among other contaminants in black-market marijuana vaping products. To date, there have been 23 deaths from vaping-related illness, and about 1,100 cases of the illness nationwide. Yesterday, a

(Beyond Pesticides, October 10, 2019) Mysterious vaping illnesses across the country could be related to pesticide exposure, among other contaminants in black-market marijuana vaping products. To date, there have been 23 deaths from vaping-related illness, and about 1,100 cases of the illness nationwide. Yesterday, a  (Beyond Pesticides, October 9, 2019) Pesticide industry propaganda promoting the safety of glyphosate-based herbicides took another hit last month, as a study published by an international team of researchers found the chemical had the potential to induce breast cancer when combined with other risk factors. The study,

(Beyond Pesticides, October 9, 2019) Pesticide industry propaganda promoting the safety of glyphosate-based herbicides took another hit last month, as a study published by an international team of researchers found the chemical had the potential to induce breast cancer when combined with other risk factors. The study,  (Beyond Pesticides, October 8, 2019)Â As medicinal and recreational marijuana continue to be legalized in a growing number of states, concerns about the safety of the burgeoning industryâhow the substance is grown, harvested, processed, distributed, sold, and usedâhave emerged. Pesticides have not been registered for use in cannabis production, yet they are being widely used under state-adopted enforcement levels that imply safety, but not subject to any standard of review that meets pesticide registration standards.

(Beyond Pesticides, October 8, 2019)Â As medicinal and recreational marijuana continue to be legalized in a growing number of states, concerns about the safety of the burgeoning industryâhow the substance is grown, harvested, processed, distributed, sold, and usedâhave emerged. Pesticides have not been registered for use in cannabis production, yet they are being widely used under state-adopted enforcement levels that imply safety, but not subject to any standard of review that meets pesticide registration standards. (Beyond Pesticides, October 4, 2019)Â A Circuit Court

(Beyond Pesticides, October 4, 2019)Â A Circuit Court

(Beyond Pesticides, October 2, 2019)Â New data gleaned from the Kuakini Honolulu Heart Program â a longitudinal study of men of Japanese descent living on Oahu â

(Beyond Pesticides, October 2, 2019)Â New data gleaned from the Kuakini Honolulu Heart Program â a longitudinal study of men of Japanese descent living on Oahu â  (Beyond Pesticides, October 1, 2019) Commonly used fungicides induce trophic cascades that can lead to the overgrowth of algae, according to research published in the journal

(Beyond Pesticides, October 1, 2019) Commonly used fungicides induce trophic cascades that can lead to the overgrowth of algae, according to research published in the journal  (Beyond Pesticides, September 30, 2019) A warm thank you to all who have sent in comments for the Fall 2019 National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) meeting. We are sending out a second reminder so that those who have not commented can take this opportunity to do so. If you have already submitted, we encourage you to make a second round of comments to make sure your voice is heard!

(Beyond Pesticides, September 30, 2019) A warm thank you to all who have sent in comments for the Fall 2019 National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) meeting. We are sending out a second reminder so that those who have not commented can take this opportunity to do so. If you have already submitted, we encourage you to make a second round of comments to make sure your voice is heard! (Beyond Pesticides, September 27, 2019) The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) will be required to protect the habitat of the

(Beyond Pesticides, September 27, 2019) The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) will be required to protect the habitat of the

(Beyond Pesticides, September 24, 2019) âOver increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song,â Rachel Carson wrote in Silent Spring in 1962. New research finds that quote has held true since it was written. Over three billion birds, or 29% of 1970s abundance have been lost in North America over the last 50 years.

(Beyond Pesticides, September 24, 2019) âOver increasingly large areas of the United States, spring now comes unheralded by the return of the birds, and the early mornings are strangely silent where once they were filled with the beauty of bird song,â Rachel Carson wrote in Silent Spring in 1962. New research finds that quote has held true since it was written. Over three billion birds, or 29% of 1970s abundance have been lost in North America over the last 50 years. (Beyond Pesticides, September 23, 2019)Â Â Your voice is making a difference! Last month, thousands of individuals took action through Beyond Pesticides and other environmental groups to express concern to their federal lawmakers about the Trump Administration’s assault on the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In response, U.S. Representatives Grijalva, Beyer, and Dingell in the House, and Senator Udall in the Senate have introduced theÂ

(Beyond Pesticides, September 23, 2019)  Your voice is making a difference! Last month, thousands of individuals took action through Beyond Pesticides and other environmental groups to express concern to their federal lawmakers about the Trump Administration’s assault on the Endangered Species Act (ESA). In response, U.S. Representatives Grijalva, Beyer, and Dingell in the House, and Senator Udall in the Senate have introduced the

(Beyond Pesticides, September 17, 2019) The poisonous farm fields migratory birds forage on during their journey reduce their weight, delay their travel, and ultimately jeopardize their survival, according to new research published in the journal

(Beyond Pesticides, September 17, 2019) The poisonous farm fields migratory birds forage on during their journey reduce their weight, delay their travel, and ultimately jeopardize their survival, according to new research published in the journal

(Beyond Pesticides, September 13, 2019)Â

(Beyond Pesticides, September 13, 2019)  (Beyond Pesticides, September 12, 2019) This September, adults will join in

(Beyond Pesticides, September 12, 2019) This September, adults will join in  (Beyond Pesticides, September 11, 2019) Germany is the latest entity to take action on getting

(Beyond Pesticides, September 11, 2019)Â Germany is the latest entity to take action on getting