21

Mar

(Beyond Pesticides, March 21, 2024) Alarming levels of a hazardous pesticide plant growth regulator linked to reproductive and developmental effects, chlormequat, is found in 90% of urine samples in people tested, raising concerns about exposure to a chemical that has never been registered for food use in the U.S. but whose residues are permitted on imported food. Published in the Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology in February 2024 and led by Environmental Working Group toxicologist Alexis Temkin, PhD, a pilot study finds widespread chlormequat exposure to a sampling of people from across the country. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulations only permit the use of chlormequat on ornamental plants and not food crops grown in the U.S. As explained in the journal article, ‚ÄúIn April 2018, the U.S. EPA published acceptable food tolerance levels for chlormequat chloride in imported oat, wheat, barley, and some animal products, which permitted the import of chlormequat into the U.S. food supply.‚ÄĚ In 2020, EPA increased the allowable level of chlormequat in food. Then in April 2023, EPA proposed allowing the first-ever U.S. use of chlormequat on barley, oat, triticale (a hybrid of wheat and rye), and wheat. Existing regulatory standards explain the higher detections of the chemical in U.S. residents tested, as observed in the study and pending domestic use allowances will only increase exposure further. Advocates note that this study on one pesticide reflects systemic failures in the regulatory review process.¬†

Like many other pesticides, exposure to chlormequat raises significant concerns about the potential impact on public health, as animal studies have linked chlormequat to reduced fertility, harm to the reproductive system, and altered fetal growth, including negative impacts on reproduction and post-birth health, and proper weight and bone development. The study notes that published toxicological research has found potential health effects from chlormequat exposure at doses lower than the current regulatory limits set by the EPA and European Food Safety Authority (EFSA).

Additionally, chlormequat residues are found in over 90% of conventional oat-based products, while organic food products showed minimal contamination. The report argues the necessity for ongoing biomonitoring to assess the potential health impacts of chlormequat exposure at environmentally relevant levels, especially during critical periods such as pregnancy. Advocates point to the chlormequat findings as evidence of the importance of supporting organic agriculture and organic food products as a means of avoiding harmful chemical exposure.

Research findings and methods

This study investigates the presence of chlormequat in urine samples collected from adults in the U.S. between 2017-2023. Study results detect chlormequat in most urine samples, with detection frequencies increasing from 69% in 2017 to 90% in 2023. Food products purchased in the U.S. and U.K. were also tested, with chlormequat found more frequently in U.S. non-organic oat products than wheat. U.K. oat food samples have 15 times higher chlormequat levels than U.S. samples. The study suggests exposure levels may rise further if chlormequat is approved for domestic agricultural use in the U.S. It raises potential health concerns given toxicology studies linking chlormequat exposure to reduced fertility and impacts on fetal growth.

Toxicological effects at doses lower than EPA’s allowed reference dose (and below the safety limit set by the European regulatory agency)

The pervasive presence of chlormequat in the U.S. population and its detection in conventional oat-based and some wheat-based products demand a comprehensive reevaluation of the risks associated with this chemical, which should raise alarm at the EPA‚Äôs current consideration of allowing chlormequat to be used in the U.S. on non-organic agricultural products. The report notes, ‚ÄúAdditionally, the regulatory thresholds do not consider the adverse effects of mixtures of chemicals that may impact the reproductive system, which have been shown to cause additive or synergistic effects at doses lower than for individual chemical exposures [22], raising concerns about the potential health effects associated with current exposure levels, especially for individuals on the higher end of exposure in general populations of Europe and the U.S.‚ÄĚ

Specifically, the report noted that animal studies showed:

- Mice and pigs exposed to doses under the EPA’s reference dose (allowed exhibited reduced fertility, harm to the reproductive system, and altered fetal growth.

- Pregnant mice exposed to a dose equal to the no observed adverse effect level used to set the EPA limit experienced altered fetal growth and metabolic/body composition changes in neonatal mice.

Additionally, the regulatory thresholds do not account for potential additive or synergistic effects from mixtures of chemicals that impact the reproductive system, as some studies have demonstrated.

This raises concerns that the current exposure levels in some populations, especially those with elevated exposures, could still pose health risks. The study argues that the toxicology research suggests a reevaluation of the safety thresholds may be warranted to better protect public health, and expanded biomonitoring is warranted. Beyond Pesticides advocates for consumers to avoid unnecessary exposure by eating organic food and certified organic food products and to support a systemic change to organic and regenerative organic agriculture.

Assessing chlormequat exposure in U.S. food products purchased between 2022 and 2023

To assess whether chlormequat levels detected in U.S. urine samples correspond to potential dietary exposure, analysis was conducted on oat and wheat-based food products acquired in the U.S. during 2022 and 2023. Results found that non-organic oat products contain chlormequat with a median concentration of 104 parts per billion (ppb). This variability could be attributed to differences in product sourcing, including domestic versus Canadian origins (chlormequat is widely used in Canadian grain crops, while not currently allowed in U.S. agriculture), and whether the oats were treated with chlormequat. In contrast, U.K. food samples demonstrated a higher prevalence of chlormequat, especially in wheat-based products like bread, where 90% of samples had detectable chlormequat levels, and in oat products, where levels were over 15 times higher than those found in U.S. samples. Beyond Pesticides reported in 2014 on U.K. contamination of bread supply, when it was found that over 60% of the country’s bread supply was tainted with chlormequat and glyphosate pesticide residues.

The presence of chlormequat in urine samples prior to 2018 suggests exposure despite the absence of established food tolerance levels for this pesticide in the U.S. The study hypothesizes that such exposure likely resulted from dietary sources, considering chlormequat’s rapid degradation. According to the authors, ‚ÄúThese data indicate likely continuous exposure given the short half-life of chlormequat in vivo, with low levels from 2017 to 2022 and higher exposure levels in 2023.‚ÄĚ The formation of chlormequat from choline precursors in wheat and egg powder has been observed under the high temperatures used in food processing, leading to concentrations ranging from 5 to 40 ng/g. These findings imply that dietary exposure to chlormequat could stem from its formation during food processing and from imported products treated with chlormequat. Factors such as geographical location, dietary habits, and occupational exposure in environments like greenhouses could influence individual exposure levels.

This research underscores the need for a broader and more varied analysis of processed foods to thoroughly investigate potential dietary sources of chlormequat, especially in individuals with elevated exposure levels. Future research should encompass the examination of historical urine and food samples, alongside dietary and occupational surveys, to provide a comprehensive understanding of chlormequat exposure sources within the U.S. population. Given that chlormequat is presently restricted to imported oat and wheat products in the U.S., with its domestic use on non-organic crops under review by EPA, there is potential for increased chlormequat levels in the food supply and, consequently, higher exposure levels among the U.S. population.

This study constitutes the first biomonitoring of chlormequat presence in the urine of adults in the United States, expanding the scope of monitoring beyond limited research focused on the United Kingdom and Sweden. A comprehensive pesticide biomonitoring effort involving over 1,000 Swedish adolescents from 2000 to 2017 revealed a 100% detection rate for chlormequat, underscoring the widespread use of chlormequat in the UK, European Union (and Canada), and resulting human exposure levels.

The discernible spike in urinary chlormequat concentrations in 2023, relative to preceding years, is potentially indicative of its recent introduction into the American food chain, a development that coincides with EPA  of permissible chlormequat levels in food in 2018 and an increase in these limits for oats in 2020.

In assessing whether the urinary chlormequat concentrations reflected potential dietary exposure, this research measured chlormequat levels in oat and wheat-based food products available in the U.S. market in 2022 and 2023. Oat products exhibited a higher frequency of chlormequat presence compared to wheat products, with significant variability in chlormequat content among oat-based items, potentially attributable to differences in sourcing of oats from the U.S. versus Canada. The study suggests that exposure to chlormequat predates 2018, prior to the establishment of food tolerance levels in the U.S., hypothesizing that such exposures were likely dietary in nature given chlormequat’s short half-life. The absence of chlormequat monitoring in U.S. food products and historical data complicates this assertion. However, the natural formation of chlormequat from choline precursors under high-temperature conditions typical of food processing has been documented, leading to chlormequat concentrations within a similar specific range. The variability in chlormequat levels observed in food samples, including those from the only organic oat-based product out of eight organic oat products tested, had low levels of chlormequat, aligning with this phenomenon of natural formation, and suggesting dietary exposure as a plausible source of the pre-2023 urinary chlormequat levels. The elevated levels detected in 2023 may result from dietary exposure to naturally occurring chlormequat and the consumption of imported, chlormequat-treated products. What is unequivocal is the widespread use of chlormequat in Canada, the U.K., and the European Union, where, as previously noted, human biomonitoring studies showed the U.K. and Sweden have almost 100% exposure in the population tested.¬†

Solutions found in buying organic oat and wheat products, supporting organic farming

Organic food products have been found to have zero contact with pesticides unless due to herbicidal drift from other farming operations. The best defense against pesticide exposure is, whenever possible, choosing to purchase and consume organic. For more information on pesticide residue exposure for different organic versus non-organic forms of common produce, please check out the pages on Eating with a Conscience and Buying Organic Products (on a budget!). For those with some background experience or interest in gardening, see Grow Your Own Organic Food for best practices, tips, and resources to get started. If you believe that you were exposed to pesticides, please click to access our section on Pesticide Emergencies.

Beyond Pesticides continues to closely monitor potential EPA actions to register chlormequat for use in the U.S. on non-organic crops. Click here to subscribe to action alerts and a weekly newsletter of the Daily News!

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Sources

A pilot study of chlormequat in food and urine from adults in the United States from 2017 to 2023, Journal of Exposure Science and Environmental Epidemiology, February 15, 2024 https://www.nature.com/articles/s41370-024-00643-4

A mixture of 15 phthalates and pesticides below individual chemical no observed adverse effect levels (NOAELs) produces reproductive tract malformations in the male rat, Environment International, November 2021 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160412021002403

Maternal chlormequat chloride exposure disrupts embryonic growth and produces postnatal adverse effects, Toxicology, September 2020 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32622971/

Currently used pesticides and their mixtures affect the function of sex hormone receptors and aromatase enzyme activity, Toxicology and Applied Pharmacology, 2013 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0041008X13003013

Posted in Agriculture, Alternatives/Organics, chemical sensitivity, Chemicals, chlormequat, contamination, Disease/Health Effects, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Infertility, multi-generational effects, Pesticide Mixtures, Pesticide Regulation, Pesticide Residues, Regenerative, Reproductive Health, Respiratory Diseases, Respiratory Problems, synergistic effects, Uncategorized by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

20

Mar

(Beyond Pesticides, March 20, 2024) A report by CBAN unpacks the ecosystem and wildlife health impacts of genetically engineered (GE) corn in the context of Mexico’s 2023 decision to stop its importation into the country. The phase out of genetically modified (GM) corn imports into Mexico was immediately challenged by the U.S. and Canadian governments as a trade violation under the 2020 U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA), which replaced the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) as the primary vehicle for North American trade policy. In August 2023, the U.S. Trade Representative set up a dispute settlement panel under USMCA to stop Mexico from going forward with its ban. There has been no public update from the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative as of this writing.

The CBAN report highlights the scientific rationale underpinning Mexico‚Äôs decision to ‚Äúsafeguard the integrity of native corn from GM contamination and to protect human health‚ÄĚ with this ban. In 2020, Mexico announced a four-year phase-out of the weed killer glyphosate, which along with other petrochemical herbicides is integral to GM corn production. When Mexico‚Äôs Minister of the Environment announced the phase-out, he said it is part of an effort to transform the country‚Äôs food system to one that is ‚Äúsafer, healthier and more respectful of the environment (m√°s seguro, m√°s sano y respetuoso con el medio ambiente).‚ÄĚ The Minister said that Mexico would be looking to Indigenous farming practices as an alternative. In addition to traditional agriculture, Beyond Pesticides points to organic agricultural practices as a systems approach that simultaneously prohibits the use of toxic petrochemical pesticides such as glyphosate and genetically engineered crops.

The CBAN report explains the background on the USMCA trade deal:

“The United States and Canada are challenging the measures in Mexico’s Presidential Decree of February 13, 2023 that pertain to the use of genetically modified [corn]:

- [A]n immediate ban on the use of GM corn for human consumption (white corn intended for use in dough and tortillas);

- [T]he revocation of existing GM corn authorizations and a halt to future approvals; and

- [A] phase-out of the use of GM corn for animal feed and processed food ingredients.

Mexico‚Äôs decree also phases out the use of the herbicide glyphosate but this measure is not being challenged by the US and Canada. Mexico already bans the cultivation of GM corn.‚ÄĚ

The USMCA was adopted with the stated goal of creating ‚Äúa more balanced environment for trade, will support high-paying jobs for Americans, and will grow the North American economy.‚ÄĚ

In deciding to ban GE corn, Mexico compiled a database of scientific studies that document the health impacts to insects, pollinators, and animals fed GE corn, as well as the adverse health impacts of glyphosate on humans. In addition to herbicide-tolerant GE crops, the CBAN report states, ‚ÄúMost GM corn plants are genetically modified to kill insect pests. The GM plants express a toxin from the soil bacteria Bacillus thuringiensis (Bt) that is known to harm the guts of specific types of insects but not others. Farmers have long used Bt as a spray to kill pests but the Bt toxins in GM crops are different from this natural Bt in structure, function, and biological effects.‚ÄĚ The report continues, ‚ÄúIn fact, peer-reviewed studies across the scientific literature continue to find that Bt toxins in GM plants can harm insects (spiders, wasps, ladybugs, and lacewings, for example) that are not the intended targets.‚ÄĚ

Similar to the threat of pesticide drift is the threat of genetic drift -typically pollen from a GE crop field being carried by wind or pollinators like honey bees, which are known to travel six miles or further. The National Organic Standards Board, in a unanimous vote in the spring of 2012, sent a letter¬†to Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack saying, ‚ÄúWe see the potential of contamination by genetically engineered crops as a critical issue for organic agricultural producers and the consumers of their products. There are significant costs to organic producers and handlers associated with preventing this contamination and market loss arising from it.‚Ä̬†

Within Mexico, there is over a decade of judicial and executive actions against the spread of GE and genetically modified crops, as well as the use of toxic petrochemical pesticides. As reported by Beyond Pesticides in 2013: ‚Äú[A] judge in Mexico issued an injunction against the planting and selling of genetically engineered (GE) corn seed, effective immediately, within the country‚Äôs borders. The decision comes nearly two years after the Mexican government temporarily rejected the expansion of GE corn testing, citing the need for more research. The decision prohibits agrichemical biotech companies, including Monsanto, DuPont Pioneer, Syngenta, PHI Mexico, and Dow AgroSciences, from planting or selling GE corn seed in Mexico.‚ÄĚ Then in 2020, Mexico announced the phase out of glyphosate from use or importation into the country by 2024. Mexico joins several other nations that have issued bans, including Germany (the country where Bayer was founded), Luxembourg, and Vietnam. See Genetic Engineering for a list of resources regarding state and local action against GE crops and the corresponding section on Daily News.

The U.S. government and corporate agribusinesses have a history of intervening when other countries or advocates in the U.S. move to ban glyphosate use or advance restrictions on genetically engineered or modified crops. Farmers and environmentalists have taken action in an effort to prevent the proliferation of new pesticide products, including Enlist Duo (glyphosate and 2,4 D hybrid with inert ingredients). A 2017 Daily News reported that: ‚Äú[A] coalition of farmers and environmental and public health organizations filed a lawsuit against the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for approving agrochemical giant Dow Chemical‚Äôs toxic pesticide combo, Enlist Duo, among the newer more highly toxic pesticide mixtures used in genetically engineered (GE) herbicide-tolerant crops. Comprised of glyphosate and 2,4-D (50% of the mixture in the warfare defoliant Agent Orange), Enlist Duo is typically marketed alongside commercial crops like corn, cotton and soybeans that are engineered to withstand pesticide exposure, leading to problems of resistance and driving the evolution of super weeds.‚ÄĚ A 2023 Daily News reported, ‚ÄúBritish biotechnology company Oxitec is withdrawing its application to release billions of genetically engineered mosquitoes in California, according to a recent update from the California Department of Pesticide Regulation.‚ÄĚ EPA approved the us[e of] a nucleic acid‚ÄĒdouble-stranded RNA (dsRNA)‚Äďcalled ‚Äúinterfering RNA, or RNAi‚ÄĒto silence a gene crucial to the survival of the Colorado Potato Beetle (CPB), the scourge of potato farmers around the world. (See Daily News.)

Beyond Pesticides continues to support advocates who are passionate in our mission statement of abolishing toxic petrochemical pesticides by 2032. In the spirit of human and ecological health, advocates in our network believe that organic land management and farming principles are the primary pathway forward to make these toxic practices obsolete. See Organic Agriculture and Keeping Organic Strong to learn about the health and environmental benefits of organic land management principles and opportunities to strengthen the National Organic Program as the next National Organics Standards Board (NOSB) meeting begins at the end of this month. See Parks for a Sustainable Future to learn more about the importance of organic land management principles in the context of public parks at the city and county level.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Canadian Biotechnology Action Network

Posted in Contamination, Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Genetic Engineering, International, Pesticide Drift, Pollinators, Uncategorized by: Beyond Pesticides

2 Comments

19

Mar

(Beyond Pesticides, March 19, 2024) This month the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) announced the creation of a new initiative to combat the health and environmental impacts of toxic petrochemical pesticides in agriculture. Launched by seven countries‚ÄĒEcuador, India, Kenya, Laos, Philippines, Uruguay, and Vietnam‚ÄĒthe Financing Agrochemical Reduction and Management (FARM) Programme is a $379 million initiative that ‚Äúwill realign financial incentives to prevent the use of harmful inputs in food production.‚ÄĚ This international cohort aims to phase out the use of ‚Äútoxic persistent organic pollutants (POPs)‚ÄĒchemicals which don‚Äôt break down in the environment and contaminate air, water, and food.‚ÄĚ The work of FARM echoes Beyond Pesticides call for the banning of toxic petrochemical pesticides by 2032.

The program will help countries implement their commitment to eliminate POPs and plastics in agriculture. As it is described, ‚ÄúFARM…will support government regulation to phase out POPs-containing agrochemicals and agri-plastics and adopt better management standards, while strengthening banking, insurance and investment criteria to improve the availability of effective pest control, production alternatives and trade in sustainable produce.‚ÄĚ The 2001 Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants requires signatories to adopt a range of measures to reduce and, where feasible, eliminate the release of POPs. All FARM members are signatories and most ratified the Convention as of 2006, with Laos being the most recent to ratify in 2013.

‚ÄúThe five-year programme is projected to prevent over 51,000 tons of hazardous pesticides and over 20,000 tons of plastic waste from being released,‚ÄĚ according to the latest UNEP press release. ‚Äú[W]hile avoiding 35,000 tons of carbon dioxide emissions and protecting over 3 million hectares of land from degradation as farms and farmers convert to low-chemical and non-chemical alternatives,‚ÄĚ the release continues. FARM is supported by the Global Environmental Facility, UN Development Programme, UN Industrial Development Organization, and the African Development Bank. The goal of FARM is, ‚Äúfor banks and policy-makers to reorient policy and financial resources towards farmers to help them adopt low- and non-chemical alternatives to toxic agrochemicals and facilitate a transition towards better practices.‚ÄĚ Beyond Pesticides applauds this important step FARM countries are taking to transition away from pesticide dependency; however advocates reiterate the importance of organic land management principles as an opportunity to adopt a systems change framework rather than a product substitution framework that replaces toxic pesticides with less toxic pesticides. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), POPs are ‚Äúintentionally produced chemicals currently or once used in agriculture, disease control, manufacturing, or industrial processes‚ÄĚ and ‚Äúunintentionally produced chemicals…that result from some industrial processes and from combustion.‚ÄĚ

There are cascading socio-ecological impacts of toxic pesticides, including POPs, that has been widely documented. (See Daily News.) Organochlorine compounds (OCs), including organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), are examples of persistent organic pollutants that cause adverse health impacts to wildlife including humpback whales and pandas. A 2021 study published in Environmental Pollution identifies, among female whale populations, ‚Äúlevels of POPs in blubber are higher in juveniles and subadults than in adults, primarily from the transference of contaminants from the mother to her calf.‚ÄĚ The study goes on to report previously unknown adverse health impacts, ‚Äúincluding reproductive toxicity, immune dysfunction, and increased susceptibility to disease.‚ÄĚ Meanwhile, a 2021 study published in Environmental Pollution found that the ‚ÄúQuinling Panda species [‚Äėthe rarest subspecies of giant pandas‚Äô] are generally exposed to moderate levels of OC pollution. Higher levels of OCs are present in captive pandas relative to wild pandas. The authors identify PCB and OCP residues as coming from atmospheric transportation. At the same time, the study identifies PCBs as a cancer risk to the pandas, in fact the most notable toxicant with the highest carcinogenic risk index of PCB 126 (the most potent highly toxic industrial byproduct that incites numerous adverse physiological effects).‚ÄĚ

Beyond individual animal species, POPs are emerging in remote ecosystems such as coral reefs and Arctic glaciers, leading to harmful impacts and long-term implications for biodiversity and human health. A 2021 study published in Chemosphere based on coral reefs in the South China Sea, ‚Äúindicate[d that] 17 of the 22 OCPs are detectable in seawater, and all 22 OCPs are detectable in ambient air samples from the SCS. The most prominent chemicals found in air and water samples are CHLs, HCBs, DDTs, and Drins. Although coastal corals have higher chemical concentrations than offshore species, the chemical composition is similar, with DDT and CHL¬†compounds dominant among tissue samples.‚ÄĚ The presence of OCPs in the South China Sea raises serious concerns about the long-term biodiversity impacts as they cause adverse health impacts on animals and humans alike, including ‚Äúrespiratory issues, nervous system disorders, and birth deformities to various common and uncommon cancers.‚ÄĚ A 2020 study published in Environmental Science and Technology found that POPs are found to be re-released after bioaccumulating in Arctic ice for decades, exacerbating the potential exposure levels facing marine animals, oceans, and humans as the climate crisis rages on and causes Arctic ice to melt in the coming decades. POPs are also found to have adverse health impacts on humans, including prenatal and early-life exposure leading to chronic illnesses such as developmental disorders to cancer. Persistent organic pollutants can also act like endocrine disruptors and studies link their exposure to female reproductive health disorders such as endometriosis.

As the U.S. EPA states, ‚ÄúMany POPs were widely used during the boom in industrial production after World War II, when thousands of synthetic chemicals were introduced into commercial use.‚ÄĚ After the war, the chemical industry looked to commercialize the petrochemical pesticide products for use in pest management and public health. ‚ÄúJust as U.S. industry and public forged an alliance to prepare for World War II, advocates must join with farmers, public health advocates, scientists, and elected officials to demand a new regulatory approach in service of public health, environmental justice, and addressing the climate crisis,‚ÄĚ says Max Sano, organic program associate at Beyond Pesticides. Advocates are steadfast in their belief that strengthening federal organic policy and standards will address the proliferation of toxic petrochemical pesticides into soil, waterways, and ecosystems. See Keeping Organic Stronger to learn how to engage in the National Organic Standards Board April meeting and public comment periods to engage in protecting and expanding climate-health-soil protections for the National Organic Program. See Pesticide-Induced Disease Database and Gateway on Pesticide Hazards and Safe Pest Management to view an ongoing list of scientific studies that link pesticide exposure, such as POPs, to chronic illnesses to learn how to engage with elected officials and participate in regulatory reviews with the aim of strengthening their regulation and minimizing additional exposure levels.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: United Nations Environment Programme

Posted in Breakdown Chemicals, Chemicals, International, organochlorines, Plastic, Uncategorized, United Nations by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

18

Mar

(Beyond Pesticides, March 18, 2024) Comments are due by 11:59 pm EDT on April 3, 2024. Organic standard setting provides for democratic input, full transparency, and continuous improvement. The current public comment period is an important opportunity for the public to engage with the organic rulemaking process to ensure that the National Organic Standards Board (NOSB) and the USDA National Organic Program uphold the values and principles set forth in the Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA). With the threats to health, biodiversity, and climate associated with petrochemical pesticide and fertilizer use in chemical-intensive land management, advocates stress that this is critical time to keep organic strong and continually improving.

Organic maintains a unique place in the food system because of its high standards, public input, inspection system, and enforcement mechanism. But, organic will only grow stronger if the public participates in voicing positions on key issues to the NOSB, a stakeholder advisory board. Beyond Pesticides has identified key issues for the upcoming NOSB meeting below!

The NOSB is receiving written comments from the public on key issues through April 3, 2024. This precedes the upcoming public comment webinar on April 23 and 25 and the deliberative hearing on April 29 through May 1‚ÄĒconcerning how organic food is produced.¬†Written comments must be submitted by 11:59 pm EDT on April 3¬†through the¬†“click-and-submit” form linked¬†or via¬†Regulations.gov.

Sign up for a 3-minute comment to let U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) know how important organic is at the webinar by April 3. Links to the virtual comment webinars will be provided approximately one week before the webinars.

>>Submit your written comment HERE to the National Organic Standard Board by April 3. (See high-priority issues below.)

The NOSB is responsible for guiding USDA in its administration of The Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA), including the materials allowed to be used in organic production and handling. The role of the NOSB is especially important as we depend on organic production to protect our ecosystem, mitigate climate change, and enhance our health.

A draft meeting agenda is available¬†here.‚ÄĮ¬†And a detailed agenda, along with the proposals, are available¬†here.¬†

Written comments are due by 11:59 pm ET on Wednesday, April 3, 2024, as well as registration for oral comments. Oral comment sign-ups fill up fast! >> Sign up for oral comments here.

The NOSB plays an important role in bringing the views of organic consumers and producers to bear on USDA, which is not always in sync with organic principles and not giving sufficient support to the critical need to end the use of petrochemical pesticides and fertilizers. There are many important issues on the NOSB agenda this Spring.¬†For a complete discussion, see¬†Keeping Organic Strong¬†and the¬†Spring 2024 Beyond Pesticides’ issues¬†webpage. ¬†

Some of our high-priority issues for the upcoming NOSB meeting:

- Reject the petition to allow unspecified ‚Äúcompostable materials‚ÄĚ in compost allowed in organic production. Compost made in organic production should use plant and animal waste, and not synthetic materials that could introduce hazardous contaminants like¬†PFAS¬†and¬†microplastics. The current regulations require compost to be made from manure and plant wastes, allowing only synthetics on the National List‚ÄĒthat is, those that have specifically been approved by the NOSB and USDA through a public comment process. The only synthetic inputs into compost that are currently allowed are newspaper and other paper. A¬†petition seeks to allow ‚Äúcompost feedstocks‚ÄĚ that might include, for example, ‚Äúcompostable‚ÄĚ food containers.¬†

Both organic and nonorganic farms¬†have been taken out of production¬†because of PFAS contamination, and microplastics can have a¬†synergistic effect¬†with PFAS. Even worse are potential contaminants we don’t know. Current PFAS contamination came from past use of biosolids not known to be a source of ‚Äúforever chemicals.‚ÄĚ Biosolids‚ÄĒfortunately never allowed in organic production‚ÄĒshould be a lesson to remember.¬†¬†

- Eliminate nonorganic ingredients in processed organic foods as a part of the sunset review. Materials listed in ¬ß205.606 in the organic regulations are nonorganic agricultural ingredients that may comprise 5% of organic-labeled processed foods. The intent of the law is to allow restricted nonorganic ingredients (fully disclosed and limited) only when their organic form is not available. However, materials should not remain on ¬ß205.606 if they can be supplied organically, and we can now grow virtually anything organically. The Handling Subcommittee needs to ask the question of potential suppliers, ‚ÄúCould you supply the need¬†if the organic form is required?‚ÄĚ The materials on ¬ß205.606 up for sunset review this year are made from agricultural products that can be supplied organically and thus should be taken off the National List of allowed materials.¬†

- Ensure that so-called ‚Äúinert‚ÄĚ ingredients in the products used in organic production meet the criteria in OFPA with an NOSB assessment.¬†The NOSB has passed repeated recommendations instructing USDA’s National Organic Program (NOP) to replace the generic listings for ‚Äúinerts‚ÄĚ that may be biologically and chemically active¬†(currently using¬†EPA Lists 3, 4A, and 4B ‚Äúinerts‚ÄĚ) with specific substances approved for use. NOP must allocate resources for this project. Recent appropriations have increased for NOP, and some of this money must be used for the evaluation of ‚Äúinert‚ÄĚ ingredients to ensure compliance with the law and to maintain the integrity of the USDA organic label.

OFPA provides stringent criteria for allowing synthetic materials to be used in organic production. In short, the NOSB must judge‚ÄĒby a supermajority‚ÄĒthat the material would not be harmful to human health or the environment, is necessary to the production or handling of agricultural products, and is consistent with organic farming and handling. These criteria have been applied to ‚Äúactive‚ÄĚ ingredients, but not to ‚Äúinert‚ÄĚ ingredients, which make up the largest part of pesticide products‚ÄĒup to 90% or more.

A comparison of the hazards posed by active and ‚Äúinert‚ÄĚ ingredients used in organic production reveals that in seven of 11 categories of harm, more ‚Äúinerts‚ÄĚ than actives pose a hazard. The NOSB and NOP must act on ‚Äúinerts‚ÄĚ NOW and meet OPFA standards.

>> Submit your written comment HERE to the National Organic Standard Board by April 3.

Comment to NOSB

I would like to address three priority issues in this comment that are of concern to me as a stakeholder in organic.

(1) Reject the petition to allow unspecified ‚Äúcompostable materials‚ÄĚ in compost allowed in organic production.

Compost made in organic production should use plant and animal waste, and not synthetic materials that could introduce hazardous contaminants like PFAS and microplastics. The current regulations require compost to be made from manure and plant wastes, allowing only synthetics on the National List‚ÄĒthat is, those that have specifically been approved by the NOSB and USDA through a public comment process. The only synthetic inputs into compost that are currently allowed are newspaper and other paper. A petition seeks to allow ‚Äúcompost feedstocks‚ÄĚ that might include, for example, ‚Äúcompostable‚ÄĚ food containers.¬†

Both organic and nonorganic farms have been taken out of production because of PFAS contamination, and microplastics can have a synergistic effect with PFAS. Even worse are potential contaminants we don‚Äôt know. Current PFAS contamination came from past use of biosolids not known to be a source of ‚Äúforever chemicals.‚ÄĚ Biosolids‚ÄĒfortunately never allowed in organic production‚ÄĒshould be a lesson to remember.

(2) Eliminate nonorganic ingredients in processed organic foods as a part of the sunset review.

Materials listed in ¬ß205.606 in the organic regulations are nonorganic agricultural ingredients that may comprise 5% of organic-labeled processed foods. The intent of the law is to allow restricted nonorganic ingredients (fully disclosed and limited) only when their organic form is not available. However, materials should not remain on ¬ß205.606 if they can be supplied organically, and we can now grow virtually anything organically. The Handling Subcommittee needs to ask the question of potential suppliers, ‚ÄúCould you supply the need if the organic form is required?‚ÄĚ The materials on ¬ß205.606 up for sunset review this year are made from agricultural products that can be supplied organically and thus should be taken off the National List of allowed materials.

(3) Ensure that so-called ‚Äúinert‚ÄĚ ingredients in the products used in organic production meet the criteria in OFPA with an NOSB assessment.

The NOSB has passed repeated recommendations instructing USDA‚Äôs National Organic Program (NOP) to replace the generic listings for ‚Äúinerts‚ÄĚ that may be biologically and chemically active¬† (currently using EPA Lists 3, 4A, and 4B ‚Äúinerts‚ÄĚ) with specific substances approved for use. NOP must allocate resources for this project. Recent appropriations have increased for NOP, and some of this money must be used for the evaluation of ‚Äúinert‚ÄĚ ingredients to ensure compliance with the law and to maintain the integrity of the USDA organic label.

OFPA provides stringent criteria for allowing synthetic materials to be used in organic production. In short, the NOSB must judge‚ÄĒby a supermajority‚ÄĒthat the material would not be harmful to human health or the environment, is necessary to the production or handling of agricultural products, and is consistent with organic farming and handling. These criteria have been applied to ‚Äúactive‚ÄĚ ingredients, but not to ‚Äúinert‚ÄĚ ingredients, which make up the largest part of pesticide products‚ÄĒup to 90% or more.

A comparison of the hazards posed by active and ‚Äúinert‚ÄĚ ingredients used in organic production reveals that in seven of 11 categories of harm, more ‚Äúinerts‚ÄĚ than actives pose the hazard. The NOSB and NOP must act on ‚Äúinerts‚ÄĚ NOW and meet the standards of the Organic Foods Production Act.

Thank you for your consideration of my comments.

Posted in Agriculture, Alternatives/Organics, Announcements, Biosolids, compost, contamination, National Organic Standards Board/National Organic Program, Organic Foods Production Act OFPA, Pesticide Regulation, PFAS, Take Action, Uncategorized, US Department of Agriculture (USDA) by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

15

Mar

(Beyond Pesticides, March 15, 2024) Toxic pesticides harm all beings and ecosystems, including coral reefs. Large benthic foraminifera (LBF) are single-celled organisms found on reefs that face adverse metabolic impacts after exposure to the weed killer glyphosate, fungicide tebuconazole, and insecticide imidacloprid, according to a study published in Marine Pollution Bulletin. The study found that ‚Äúeven the lowest doses of the fungicide and herbicide caused irreparable damage to the foraminifera and their symbionts.‚ÄĚ Beyond Pesticides reiterates our mission of banning toxic petrochemical pesticides by 2032 and that this goal applies to land and water exposure to pesticides. LBFs are typically used as bioindicators for coral health because they are found in substantial quantities and gathering data is not intrusive or damaging to reef health.

Researchers in this study screened three different pesticides (one insecticide, one fungicide, and one herbicide) at three different concentration levels. The experiments were performed in six well-samples, each with 10mL of filtered artificial seawater and a singular LBF. The control plates are artificial seawater and the experimental plates include artificial seawater with the addition of three pesticides (imidacloprid, glyphosate, and tebuconazole). Each pesticide was applied at low, medium, and high doses to measure the direct impacts of each pesticide after dilution in seawater. The research team conducted two different experiments, one based on pulse-amplitude-modulation (PAM) fluorometry and the other to measure isotopic uptake. For the PAM fluorometry experiment the researchers ‚Äúmeasured the photosynthetic performance of the photosymbionts [an organism in a photosymbiotic relationship] for two weeks at days 1, 3, 5, 7 and 14 using variable chlorophyll fluorescence imaging of photosystem II (PSII; Imaging PAM Microscopy Version‚ÄďWalz GmbH; excitation at 620 nm). Measurement of the variable fluorescence over the maximum quantum yield fluorescence (Fv/fm) estimates the efficiency of photosystem II []. Fv/fm serves as a proxy for the vitality of the photosymbionts [] and therefore it can be used as an indicator of the health of the foraminifera themselves [].‚ÄĚ In terms of the isotopic uptake experience, ‚ÄúTwo-way ANOVAs (level of significance p = 0.05) were run to test if the type of pesticide, the concentration and/or incubation time significantly affected uptake of 15N and 13C, respectively. Significant results were further analyzed for group differences using Tukey’s post hoc test (level of significance p = 0.05).‚ÄĚ

This study differs from existing literature in how the researchers quantified the impact based on amount of pesticide products rather than solely on the individual pesticides that make up the main ingredient of the targeted products. ‚ÄúRoundup¬© [with the active ingredient glyphosate] only contains 1 % glyphosate, in Pronto¬©Plus the active substance tebuconazole has 13.6 % and in Confidor¬© the imidacloprid concentration is 20 %, according to the manufacturer’s information,‚ÄĚ says the research team. ‚ÄúBased on that, the concentration of active pesticide substances, which can be found in the environment are not a factor of 10 smaller than ours tested, they are approximately the same concentration or even 10 times higher.‚ÄĚ The scientists in this study found that, ‚Äúthe photosynthetic area decreased as the amount of pesticide added increased and as the incubation time increased.‚ÄĚ Glyphosate-based Roundup Ready in particular ‚Äúcaused a reduction of the photosynthetic area in all foraminifera…independent of concentration.‚ÄĚ The scientists also found that, ‚ÄúForaminiferal [inorganic carbon] 13C uptake was significantly reduced at the highest pesticide concentration compared to the control (p < 0.001). The herbicide and fungicide showed comparable reductions of 13C uptake (p = 0.945), the reduction caused by the insecticide was less pronounced.‚ÄĚ

Oceans and water advocates continue to remind elected officials that we cannot talk about climate action without talking about oceans and waterways stewardship. Bodhi Patil, a UN-recognized oceans solutionist and co-creator of Ocean Uprise, a global activist accelerator initiative, guides his advocacy with the understanding that ocean health is human health. ‚ÄúMitigating toxic pollutants, excess fertilizers, pesticides, and chemicals entering upstream water bodies and flowing into downstream reef ecosystems is a direct way to reduce the stressors on critically important coral reefs‚ÄĚ says Bodhi. ‚ÄúImproved water quality and reduced water pollution will contribute to their long-term health and climate resiliency. We have to think about the ocean as a being that is connected to all waterways, because she is!‚ÄĚ

Advocates have worked tirelessly to codify ocean rights in a United Nations-recognized framework as the impacts of toxic pesticides continue to impact ocean creatures big and small. In 2023, due to the years of advocacy by people like Bodhi, 193 nations approved the draft version of the High Seas Treaty (also known as Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction), an international framework that establishes universal rights to protect the oceans from harm. To date, 88 countries have signed the treaty and two countries (Chile and Palau) have ratified the treaty in their national legislatures. At least 60 countries must ratify the High Treaty for it to become international law. The exorbitant loss of over 90% of planktonic organisms from the 1940 baseline is analogous to the decline in terrestrial pollinator loss over the past several decades. Additionally, ‚ÄúIn its 2017 risk assessment for the most widely used neonicotinoid, imidacloprid, EPA found, ‚Äė[C]oncentrations of imidacloprid detected in streams, rivers, lakes and drainage canals routinely exceed acute and chronic toxicity endpoints derived for freshwater invertebrates.‚Äô The agency evaluated an expanded universe of adverse effects data and finds that acute (short-term) and chronic (long-term) toxicity endpoints are lower (adverse effects beginning at 0.65 őľg/L (micrograms per liter)-acute and 0.01 őľg/L-chronic effects) than previously established aquatic life benchmarks (adverse effects from 34.5 őľg/L-acute and 1.05őľg/L-chronic effects).‚ÄĚ Beyond Pesticides has reported on the linkage to the climate crisis and toxic petrochemical pesticide use in relation to aquatic organisms, oceans, and water.

Beyond Pesticides acknowledges the intersectional nature of the climate crisis and that pesticide drift and exposure (including glyphosate and imidacloprid) is a problem that applies to both terrestrial and marine environments. To avoid the introduction of toxic pesticides into ecosystems at the place of origin, advocates are calling on strengthening organic standards and providing new incentives to expand the domestic production and consumption of organic foods and products. See Keeping Organic Strong to learn how to engage with the National Organic Standards Board Spring 2024 meeting. Whether or not you live in a coastal city or along a waterway, see Parks for a Sustainable Future to learn about how to transition a higher education institution or a local parks department to organic land management principles.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Marine Pollution Bulletin

Posted in Aquatic Organisms, Glyphosate, Imidacloprid, Oceans, tebuconazole, Uncategorized, Water by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

14

Mar

¬†(Beyond Pesticides, March 14, 2024)¬† A recent review in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) highlights the urgent need to address the widespread chemical pollution stemming from the petrochemical industry, underscoring the dire implications for public health. Tracey Woodruff, PhD, author and professor at the University of California San Francisco (UCSF), emphatically states in an email comment to Beyond Pesticides, “We need to recognize the very real harm that petrochemicals are having on people‚Äôs health. Many of these fossil-fuel-based chemicals are endocrine disruptors, meaning they interfere with hormonal systems, and they are part of the disturbing rise in disease.” Beyond Pesticides echoes this concern, noting that endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) include many pesticides and are linked to a plethora of health issues such as infertility, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, early puberty, as well as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Parkinson‚Äôs, Alzheimer‚Äôs, and childhood and adult cancers.¬† (See Beyond Pesticides‚Äô Disease database here and news coverage here). The review further calls on the clinical community to advocate for policy changes aimed at mitigating the health threats posed by petrochemical-derived EDCs and climate change. Beyond Pesticides urgently calls for the elimination of petrochemical pesticides and fertilizers and advocates for a systemic shift to organic regenerative agriculture.¬† This call to action is grounded in the understanding that the petrochemical industry’s growth poses existential threats to climate, human health, and biodiversity.¬†¬†

Dr. Woodruff‚Äôs article adds to a series, ‚ÄúFossil Fuel Pollution and Climate Change,‚ÄĚ that NEJM launched in 2021. The journal joined with more than 200 health journals worldwide in publishing a joint editorial ‚Äúcalling for urgent action to limit greenhouse gas emissions to protect human health, adding to growing demands from around the globe.‚Ä̬†

Highlighting the explosive growth in petrochemical production, including plastics, pesticides, and fertilizers, Dr. Woodruff’s report draws a direct line between these activities and a growing burden of chemical exposure responsible for at least 1.8 million deaths annually. As the demand for oil and gas declines due to the shift toward renewable energy sources, multinational fossil-fuel corporations have ramped up the production of plastics and other petrochemicals. This transition is highlighted in the report as a significant factor driving both climate change and increased exposure to health-impacting chemicals through contaminated air, water, food, and a range of manufactured products (including plastics, pesticides, and consumer goods). This body of work is among numerous studies pointing to the far-reaching effects of endocrine disruption on both humans and wildlife. Endocrine disruptors can cause significant harm even at very low exposure levels, with embryonic and fetal development stages being particularly vulnerable to their adverse effects. The report notes, ‚ÄúConsequently, experts believe there is no risk-free level of exposure to these chemicals across the population.‚Ä̬† The report underscores the omnipresent nature of petrochemical-derived EDCs, noting that national biomonitoring data and epidemiologic studies have detected around 150 chemicals in human bodily fluids, including during pregnancy.¬† ‚ÄúThis represents a fraction of potential EDC exposures, since standard detection technology measures less than 1% of totally chemicals in use,‚ÄĚ the authors note.¬†¬†

Of serious concern is the disproportionate impact on communities of color and low-income communities, contributing to health inequities. While the report sheds light on this disparity, it stops short of delving into the environmental justice issues specific to petrochemical pesticide use, which significantly affects farmworkers and their families (see here and here). While the report focuses on what healthcare clinicians can do to reduce EDC exposures for their patients (and includes a helpful example of an environmental exposure history and suggestions of how patients can protect themselves), Dr. Woodruff acknowledges that ‚Äúmost exposures are beyond individual control‚ÄĚ and even when one chemical is removed from consumer products, the result is often a substitution of a similar toxic chemical. ¬†

Regulatory Failure

After a nearly two decade defiance of a federal mandate to institute pesticide registration requirements for endocrine disruptors, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) accepted public comments until last month on establishing a testing protocol for pesticides. (See here for comprehensive Beyond Pesticide comments). Advocates, including Beyond Pesticides, are criticizing the agency‚Äôs proposed evaluation as too narrow. EPA never completed protocol for testing potential endocrine-disrupting pesticides that disrupt the fundamental functioning of organisms, including humans, causing a range of chronic adverse health effects that defy the common misconception (and EPA risk assessment assumption) that dose makes the poison (‚Äúa little bit won‚Äôt hurt you‚ÄĚ), when, in fact, minuscule doses (exposure) wreak havoc with biological systems. Beyond Pesticides detailed comments call for EPA to suspend or deny any pesticide registration until the agency has sufficient data to demonstrate no unreasonable adverse endocrine system risk per the mandate in Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), as amended by the 1996 Food Quality Production Act. Under FIFRA, there is an inherent presumption of risk, a pesticide is presumed to pose an unreasonable risk until reliable data demonstrate otherwise. If the agency lacks the data and/or resources to fully evaluate endocrine system risks to human health and wildlife, then the agency is obliged to deny registration of said pesticide. Further, it is not the agency but pesticide registrants that have the burden to demonstrate with adequate data that their products will not pose unreasonable adverse effects, including the inherently presumed endocrine-disrupting effects. ¬†

Beyond Pesticide’s Call for an End to Petrochemical Pesticide and Synthetic Fertilizer Use by 2032

The petrochemical industries‚Äô growth is a driver of three existential threats: climate, human health, biodiversity. In addition to the petroleum used to produce synthetic pesticides, Beyond Pesticides has reported on the plastic saturation of the planet, including through the use of plastic coating of some synthetic pesticides and fertilizers, as well as treated seeds. The reliance on petroleum-based pesticides, fertilizers, and plastics reveals a deep connection of chemical-intensive agriculture to the climate crisis and biodiversity decline and establishes a vivid contrast to organic agriculture which eschews these inputs.‚Äč‚Ä謆¬†

The plastic problem is vast and complex. A 2022 study in Environmental Science & Technology reports that plastics caused chemical pollution has the potential to ‚Äúalter vital Earth system processes on which human life depends.‚Ä̬† The inherent “chemically inert” property of plastics, once thought benign, has proven to be a double-edged sword. Under certain conditions, plastics are not benign at all; they can leach toxic chemicals into their surroundings. Moreover, plastics do not easily break down into their constituent compounds after their intended life. The result is a world where microplastics, pieces less than five millimeters in diameter, have suffused every ecosystem, as the Guardian reported from the heights of Everest to the depths of the oceans, and even in Antarctica. These microplastics, along with the toxicants they may carry, have entered the food chain, impacting marine organisms, terrestrial livestock, and humans through multiple exposure routes.¬†

Rising petrochemical production spells disaster for efforts to curb greenhouse gas emissions and avert climate catastrophe‚Äč‚Äč.¬† Agriculture is a major consumer of other plastic products, using them for purposes ranging from mulching to irrigation. The United States alone uses approximately 816 million pounds of agricultural plastics annually, with significant environmental implications due to the lack of recycling policies and the resultant soil contamination that affects crop yield and ecosystem health‚Äč‚Äč. As Center for International Environmental Law in its December 2022 reissued report, Sowing a Plastic Planet: How Microplastics in Agrochemical Are Affecting¬† our Soils, Our Food, And Our Future writes, ‚ÄúNon-plastic alternatives already exist for most of the agricultural uses of microplastics (organic and organic regenerative agriculture). Accordingly, there is no justification for allowing the continued use of microplastics in fertilizers and pesticides.‚Ä̬† In response to these and other challenges, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) and other bodies have advocated for a return to traditional, organic farming practices that eschew synthetic materials in favor of organic mulch materials, cover crops, and nonchemical management strategies. These practices reduce dependence on fossil fuel-based inputs and thus, the negative climate, health, and environmental impacts.¬† Beyond Pesticides supports the transition to organic regenerative agriculture as a comprehensive solution to the myriad problems posed by chemical and plastic use in farming. Organic agricultural approaches offer numerous benefits over chemical methods, including enhanced safety for people and the environment, improved soil health, a more nutritious and nutrient dense food supply, in many cases, superior yields and and can mitigate the effects of agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. As the Rodale Institute notes, conventional farming isn‚Äôt just contributing to the climate crisis, organic farming is essential to address it and wrote, ‚ÄúOrganic methods can produce competitive yields in good weather and outperform conventional in times of drought or flooding, and organic uses less energy and generates fewer emissions while revitalizing the soil and sequestering carbon.‚ÄĮ If we‚Äôre going to decrease farming‚Äôs impact‚ÄĒand we must decrease farming‚Äôs impact‚ÄĒthen we need organic. Because farming doesn‚Äôt only contribute to climate change; it‚Äôs greatly affected by it. And it is getting harder and harder to grow food in extreme weather.‚Ä̬†¬†

Solutions to Existential Crises of Climate, Human Health, and Biodiversity

Beyond Pesticides noted in January 2023 that there is no solution to this wide array of crises that includes continued fossil fuel use. The organization wrote: ‚ÄúWhile the solutions are in reach, tremendous public action is needed to stop the fossil fuel and agrichemical industries from their short-sighted pursuit of profit at any cost‚Ķ. Arguments are made that high intensity, industrial chemical agriculture is the only way to feed the world, and fossil fuels are the only way to provide energy. Scientific data has spelled out exactly what we are in for if we continue to endorse these dangerous myths.‚ÄĚ With chemicals, like pesticides, long advanced by the synthetic pesticide and fertilizer industry as the answer to feeding the world, the United Nations ‚ÄĮSpecial Rapporteur on the right to food‚ÄĮconcluded in 2017‚ÄĮthat industrialized agriculture has not succeeded in eliminating world hunger, and has only hurt human health and the environment in its wake.‚ÄĮ¬†

Beyond Pesticides established the Parks for a Sustainable Future program to assist with the transition to organic land management in communities across the U.S. The organization also strives to maintain the integrity of organic standards through Keeping Organic Strong campaign and historical work to transition agriculture to organic practices. In 2022, Beyond Pesticides sponsored a Climate Change Calls for Phase Out of Fossil Fuels Linked to Petrochemical Pesticides and Fertilizer series of national virtual seminars (with archived videos) covering health, biodiversity, and climate. For more on climate-friendly organic agriculture, see Daily News and the groundbreaking work of the Rodale Institute, as captured in its Farming Systems Trial ‚ÄĒ 40-Year Report, which shows the efficacy and benefits of organic agriculture. California Certified Organic Farmers Association‚Äôs Roadmap to an Organic California provides a policy framework for advancing agricultural programs that combat climate change.¬†¬†¬†

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Sources:

Health Effects of Fossil Fuel-Derived Endocrine Disruptors, Dr. Tracey Woodruff, The New England Journal of Medicine, March 7, 2024

‚ÄėExplosive growth‚Äô in petrochemical production poses risks to human health, The Guardian, March 6, 2024

Sowing a Plastic Planet: How Microplastics in Agrochemical Are Affecting  our Soils, Our Food, And Our Future, Center for International Environmental Law, Reissued December 2022

Posted in Agriculture, Alternatives/Organics, Body Burden, Cancer, Chemicals, Climate, Climate Change, contamination, Dow Chemical, Drinking Water, DuPont, Endocrine Disruption, Farmworkers, Groundwater, Herbicides, Livestock, Lung Cancer, multi-generational effects, National Organic Standards Board/National Organic Program, Oceans, PFAS, phthalates, Plastic, Reproductive Health, soil health, Synthetic Fertilizer, Synthetic Turf, Uncategorized by: Beyond Pesticides

1 Comment

13

Mar

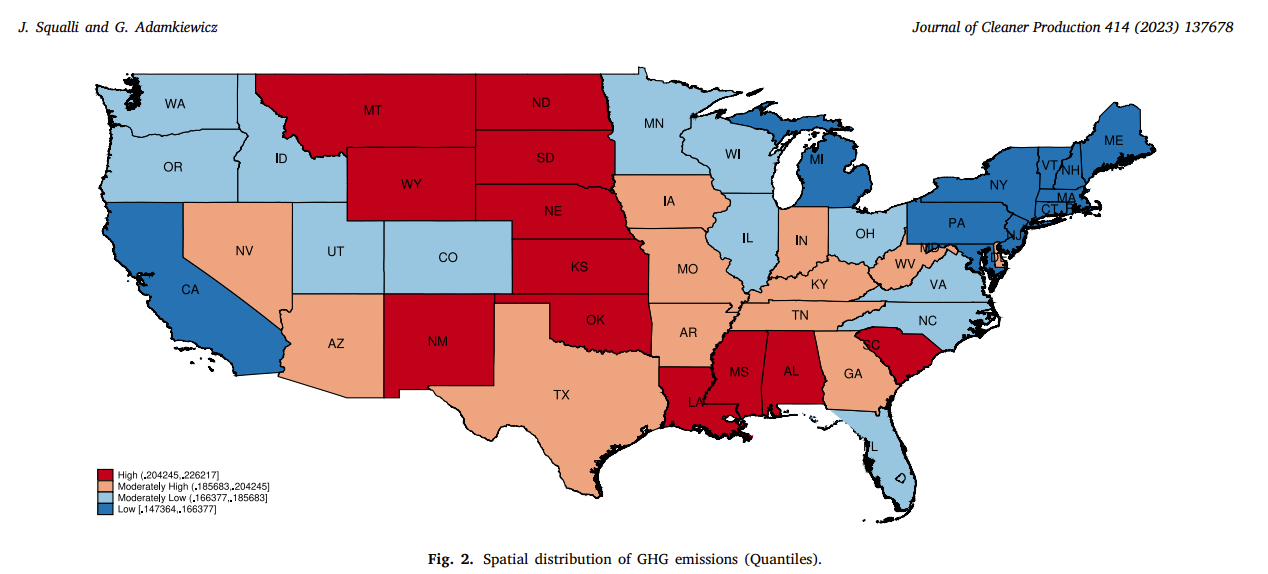

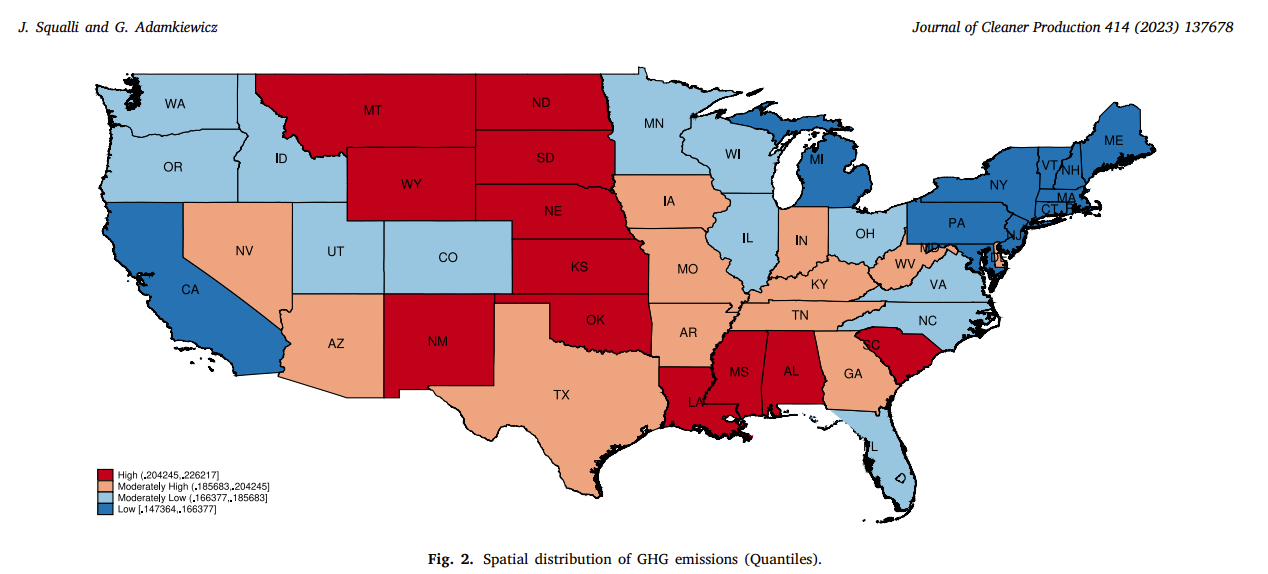

(Beyond Pesticides, March 13, 2024) A comprehensive study released in Journal of Cleaner Production in August 2023 identifies the potential for organic agriculture to mitigate the impacts of agricultural greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in the fight to address the climate crisis. In ‚ÄúThe spatial distribution of agricultural emissions in the United States: The role of organic farming in mitigating climate change,‚ÄĚ the authors determine that ‚Äúa one percent increase in total farmland results in a 0.13 percent increase in GHG emissions, while a one percent increase in organic cropland and pasture leads to a decrease in emissions by about 0.06 percent and 0.007 percent, respectively.‚ÄĚ This descriptive study affirms the urgency of Beyond Pesticides‚Äô mission to ban toxic petrochemical pesticides by 2032, given the projected adverse impacts that conventional agricultural dependence on these toxic pesticides will continue to have on people, wildlife, and ecosystems.

The study refers to various studies focused on a comparative analysis of conventional to organic farming on energy use, greenhouse gas emissions (GHGe), nutrient leaching, soil quality, and biodiversity. The consensus is that organic farming is more sustainable than conventional agriculture. For example, ‚Äú[S]everal studies comparing conventional to organic agriculture found that the latter used 10%‚Äď70% less energy per unit of land for all analyzed crops.‚ÄĚ However, measurements on a meta-analysis of soil quality and biodiversity show ‚Äúsignificant variability across studies with 16% of them showing a negative effect of organic farming on species richness.‚ÄĚ Drawing on this past research, the authors of this study accomplish what the previous research could not: ‚Äúprovide categorical supporting evidence… for the general expectation that organic farming is more environmentally sustainable than conventional farming.‚ÄĚ

These researchers used U.S. state-level data from 1997 to 2010, excluding the years 1998, 1999, and 2009 due to bad data. Additionally, researchers drew GHGe data from the World Resources Institute, economic data (e.g. ‚Äúreal per capita GDP (in chained 2009 dollars), output share for utilities, manufacturing, oil and natural gas, and transportation‚ÄĚ as a percentage of state GDP) from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Department of Commerce. Additional data was gathered from the U.S. Department of Transportation‚Äôs Federal Highway Administration, the U.S. Department of Agriculture‚Äôs Economic Research Service, and the U.S. Census Bureau.

To determine a statistical relationship between GHGe and organic farming in the U.S., the researchers use a model based on the STIRPAT (Stochastic Regression on Population, Affluence, and Technology) approach. Researchers summarize the benefits of this analytical method, ‚ÄúGiven the importance of transportation to farming, this would help examine whether the potential environmental benefits of organic food production, if any, are substantial enough to outweigh the environmental harm of transportation output embodied in organic farming.‚ÄĚ ¬†See Subsection 3.2 under Methods for a full breakdown of the empirical specifications of their methodology.

The spatial distribution (as seen above in Figure 2) of the statistical comparison between conventional and organic agricultural across all fifty states amounts to three overarching findings:

- “The spatial distribution of agricultural GHG emissions in the United States is uneven: High-emissions states are concentrated in the Great Plains extending south to NM and the southeastern area of the United States. Meanwhile, low-emissions states are in California and the northeastern region extending to MI in the north and MD in the south.

- Agriculture is a significant contributor to GDP within the high-emissions states, but organic agriculture represents only a small proportion of total farmland: The contribution of agriculture to GDP in high-emissions Great Plains states ranges from 1.11% to 5.94%, while organic agriculture as a share of total farmland ranges from 0.02% to 0.33%. In the southeastern states, the contribution of agriculture to GDP ranges from 0.39% to 1.41%, and organic agriculture ranges from 0.003% to 0.005%.

- Agriculture has a substantially lower contribution to GDP within low-emissions states, but organic agriculture represents a large proportion of total farmland: The contribution of agriculture to GDP ranges from 0.063% to 0.95%, while organic farming as a share of total farmland ranges from 0.14% to 3.13%.‚ÄĚ

Years of reporting by Beyond Pesticides corroborates the findings in the study that organic agriculture is a monitorable and critical solution to address cascading crises relating to climate change and public health. Rodale Institute‚Äôs Farming Systems Trial ‚Äď 40-Year Report highlights the success of regenerative organic agriculture:

- Organic systems achieve 3‚Äď6 times the profit of conventional production;

- Yields for the organic approach are competitive with those of conventional systems (after a five-year transition period);

- Organic yields during stressful drought periods are 40% higher than conventional yields;

- Organic systems leach no toxic compounds into nearby waterways (unlike pesticide-intensive conventional farming)

- Organic systems use 45% less energy than conventional agriculture, and

- Organic systems emit 40% less carbon into the atmosphere.

There are also numerous reports that highlight the threat of toxic petrochemical pesticides and fertilizers to the broader climate crisis. For example, a 2020 study documents the use of synthetic fertilizers as a driver of nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions. This phenomenon is of critical concern to advocates given that, ‚ÄúGrowth in nitrous oxide emissions over these last four decades has been considerable, with human-caused release, mostly from fertilizer use on cropland, increasing by 30%. Compared to pre-industrial levels, nitrous oxide levels increased 20% from all sources.‚ÄĚ While nitrous oxide emissions only make up 6 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., ‚Äúthe impact of one pound of N2O on warming the atmosphere is 265 times that of one pound of carbon dioxide.‚ÄĚ In Sub-Saharan Africa, meanwhile, years of soaring fertilizer costs (for both organic and conventional products) that began with the pandemic and continue with currency fluctuations wracked by geopolitical actions, including the Russia-Ukraine War, prevent many farmers from maintaining soil health to produce agricultural products. The climate crisis is also causing significant harm to bumblebees, according to a 2023 study that adds to research tying together the compounding impacts of extreme temperature fluctuations and toxic insecticide exposure in relation to their physical fitness and pollinating capabilities.

Beyond Pesticides strongly advocates for strengthening organic regulations to ensure the positive impact of organic principles in addressing the compounding ecological, public health, and climate crises. See Keeping Organic Strong as the National Organic Standards Board to find the opportunity to suggest changes to the National Organic Program through public hearings, comment periods, and written testimonials that will open up in April.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Journal of Cleaner Production

Posted in Agriculture, Alternatives/Organics, Biodiversity, Climate Change, State/Local, Synthetic Fertilizer, Uncategorized by: Beyond Pesticides

No Comments

12

Mar

(Beyond Pesticides, March 12, 2024) A study released in Science of the Total Environment unpacks the threat of emerging chemicals of concern (CECs), including toxic pesticides, in the groundwater of Tunisia. Researchers highlight that the impact of pesticide drift and leaching into groundwater reserves is not siloed to the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, but a key concern for most industrialized countries, including the United States. Authors of this study build on literature of CECs already conducted in the region that have broader implications for the spillover effects of pesticide regulation in broader contexts. This descriptive study and accompanying Environmental Risk Assessment (ERA) demonstrate the urgency of Beyond Pesticides’ mission to ban toxic petrochemical pesticides by 2032 because of the pervasiveness of toxic residues, be it pesticides, antibiotics, or other substances, from groundwater systems to human bodies.

The researchers performed the tests in thirteen wells in the Grombalia shallow aquifer, an area of northeast Tunisia that feeds into the Wadi El Bay watershed, which is defined as a ‚Äúhigh population density [with] intensive agricultural activity [in ‚Äėone of the most polluted areas in Tunisia‚Äô].‚ÄĚ The researchers gathered data ‚Äúduring two seasons and were analyzed with two high resolution mass spectrometry approaches: target and suspect screening. The latter was screening banned pesticides.‚ÄĚ For more information on the suspect screening approach for pesticide analysis, see Subsection 2.4 under the Materials and Methods.

The researchers identified 20 target pesticides in this study: Anabasine,¬†atrazine, bendiocarb, bentranil,¬†carbaryl,¬†carbofuran, DEET, desethylatrazine, desethylterbuthylazine, dimethomorph, fenfuram,¬†imidacloprid, isoproturon, methfuroxam, mexacarbate, propamocarb, propoxur, pyroquilon, spiroxamine, and¬†terbuthylazine. Table 2 delineates the concentrations of the most frequently detected pesticides in groundwater samples, which include DEET, mexacarbate, propoxur, desethylatrazine, and terbuthylazine. The authors are particularity concerned with the presence of ‚Äúseveral carbamate insecticides‚Ķdue to their acute and chronic toxicity.‚ÄĚ The main source of carbamate insecticides are from agricultural use, which is not surprising given that the Grombalia region‚Äôs economy is mainly based on citrus: ‚Äú77.3 percent of the irrigated area [in this region] is planted with citrus [].‚ÄĚ

‚ÄúThe most frequently quantified pesticides belong to the family of¬†triazine herbicides and carbamate insecticides. Triazines have been highly used on several agricultural crops. The occurrence of triazine herbicides in groundwater has been found very commonly [] with most likely no potential human-health concerns at the observed levels of detection [],‚ÄĚ authors report in Section 3.1.2 on the results and discussion subsection on pesticides. According to the report: ‚ÄúThe frequent detection of triazines can also be expressed as a function of their groundwater ubiquity score (GUS) index, used to predict the behavior of pollutants in groundwater. Triazines are the compounds with the highest GUS index and detection frequency, indicating their high leachability.¬†Atrazine¬†and its¬†degradation product¬†desethylatrazine are by far the most abundant herbicides detected in shallow groundwater []. Atrazine was not detected in the sampling sites, while its metabolite desethylatrazine was detected in 13 samples in both sampling campaigns []. Some researchers have shown that pesticide metabolites are often detected in groundwater at higher concentrations compared to parent compounds [] and that their presence can be more toxic than their parents. []‚ÄĚ This last line on pesticide metabolites is consistent with findings from numerous studies which demonstrate the relationship between groundwater and pesticide residue exposure and infiltration in the United States, for example, ‚Äú90 percent of Americans having at least one pesticide biomarker (includes parent compound and metabolites) in their body,‚ÄĚ according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Beyond the focus on pesticides, the study also documents the occurrence of CECs, which include ‚Äúcommonly prescribed drugs [‚Äėantimicrobials, analgesics, anti-inflammatories‚Äô], artificial sweeteners [sucralose], insecticides [fipronil], and UV filters.‚ÄĚ Sixty-nine compounds of CECS and one transformation product [metabolites or degradation products of the precursor analyte‚Äô] and 20 pesticides were detected per well, ‚Äúranging between 43 and 7384¬†ng¬†L‚ąí1¬†and 7.3 and 80¬†ng¬†L‚ąí1, respectively. The unit ng L-1 refers to one nanogram of a substance per liter of water.

Researchers in this study found it pertinent to study toxic substance exposure in Tunisian groundwater since a vast majority of the population accesses water resources through wells linked to aquifers. A 2023 Gallup poll indicates a record dissatisfaction with water quality across 81 percent of the population, particularly in southern regions of the country. ‚ÄúIndustrial waste from phosphate mining‚ÄĒphosphogypsum‚ÄĒhas led to spikes in cancer rates, infertility, and miscarriage in the region. Once famed for its thriving marine ecosystems, fish stocks have plummeted. Groundwater has been polluted, with diminishing reserves for households.‚ÄĚ One of the reasons these researchers focused on an area in northeast Tunisia was because of the lack of existing data regarding toxic substance residues in groundwater reserves generally.

There is extensive reporting by Beyond Pesticides on the human, wildlife, and ecological health implications of pesticide leaching into groundwater. For instance, marine ecosystems along the U.S. West Coast are threatened by forest management practices that permit the use of pesticides including certain herbicides (indaziflam, hexazinone, and atrazine), fungicides (fluopicolide and pyraclostrobin), and insecticides (bifenthrin and permethrin). In Arizona, the State Auditor General reported deep concern over the insufficient amount of groundwater monitoring for pesticides by the Arizona Department of Environmental Quality between 2017 and 2021 which flew in the face of legal requirements.

Beyond Pesticides continues to call on Secretary of Interior Deb Haaland to expand USGS mapping of pesticide use and monitoring and inform the U.S. Environmental Protection (EPA) Administrator Michael Regan that pesticides shown to contaminate rivers and streams must be banned. The regulation of and rulemaking around pesticide infiltration in groundwater is more complicated in the aftermath of Sackett v. EPA (2023), a Supreme Court case that limited EPA‚Äôs authority to protect critical wetland ecosystems through a narrower definition of, ‚ÄúWaters of the United States (WOTUS). In the 5-4 SCOTUS decision, regulation of groundwater (including protections against pesticide residue) was undermined once WOTUS was defined by the language, ‚Äúcontinuous surface connection to bodies.‚ÄĚ

Beyond the patchwork of state and national law that impacts water and pesticide regulation, investing in the protection of organic agricultural and land management principles is a critical approach to prevent the overwhelmingly majority of toxic petrochemical pesticides from leaching into groundwater in the first place. Beyond Pesticides affirms the decades of advocacy that went into establishing organic agriculture standards through the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990. This legislation established mechanisms for compliance, oversight, and enforcement of the national List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances to protect the public against toxic pesticides that EPA permits acceptable use in conventional, industrial agriculture. See Keeping Organic Strong as the National Organic Standards Board will offer the public the opportunity to suggest changes to the National Organic Program through public hearings, comment periods, and written testimonials in April.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Science of the Total Environment

Posted in Atrazine, Bendiocarb, Carbaryl, Chemical Mixtures, Chemicals, contamination, DEET, Groundwater, Uncategorized, Water by: Beyond Pesticides

1 Comment

11

Mar

(Beyond Pesticides, March 11, 2024) Inside a recent disagreement between the Office of the Inspector (OIG) and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency‚Äôs (EPA) Office of Pesticide Programs (OPP) on the agency‚Äôs review of pet flea and tick collars‚ÄĒleading to thousands of deaths and poisonings‚ÄĒis a basic question of the adequacy of pesticide regulation. The disagreement is over the cause of 105,354 incident reports, including 3,000 pet deaths and nearly 900 reports of human injury, and the February 2025¬†OIG report‚Äôs conclusion that ‚Äú[EPA] has not provided assurance that they can be used without posing unreasonable adverse effects to the environment, including pets.” While the disagreement focuses on a number of EPA process failures, Beyond Pesticides urges that the findings advance the need for the agency to address a key element of chemical mixtures in pesticide products not currently evaluated, potential synergistic effects‚ÄĒthe increased toxic potency created by pesticide and chemical combinations not captured by assessing product ingredients individually.¬†