(Beyond Pesticides, October 15, 2020) A review of scientific literature on the correlation between respiratory diseases and pesticides exposureâpublished in the journal Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine (AAEM), âInfluence of pesticides on respiratory pathologyâa literature reviewââfinds that exposure to pesticides increases incidents of respiratory pathologies (i.e., asthma, lung cancer, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]âor chronic bronchitis). The review by researchers at the Iuliu Hatieganuâ University of Medicine and Pharmacy Cluj-Napoca, Cluj-Napoca, Romania, looks at how pesticide exposure adversely propagates and reinforces respiratory diseases in humans. This review highlights the significance of evaluating how pesticide exposure impacts respiratory function, especially since contact with pesticides can happen at any point in the production, transportation preparation, or application treatment process. Researchers in the study note, âKnowing and recognizing these respiratory health problems of farmers and their families, and also of [pesticide] manipulators/retailers, are essential for early diagnosis, appropriate treatment, and preventive measures.â This study results are critically important at a time when exposure to respiratory toxicants increases vulnerability to Covid-19, which attacks the respiratory system, among other organic systems.

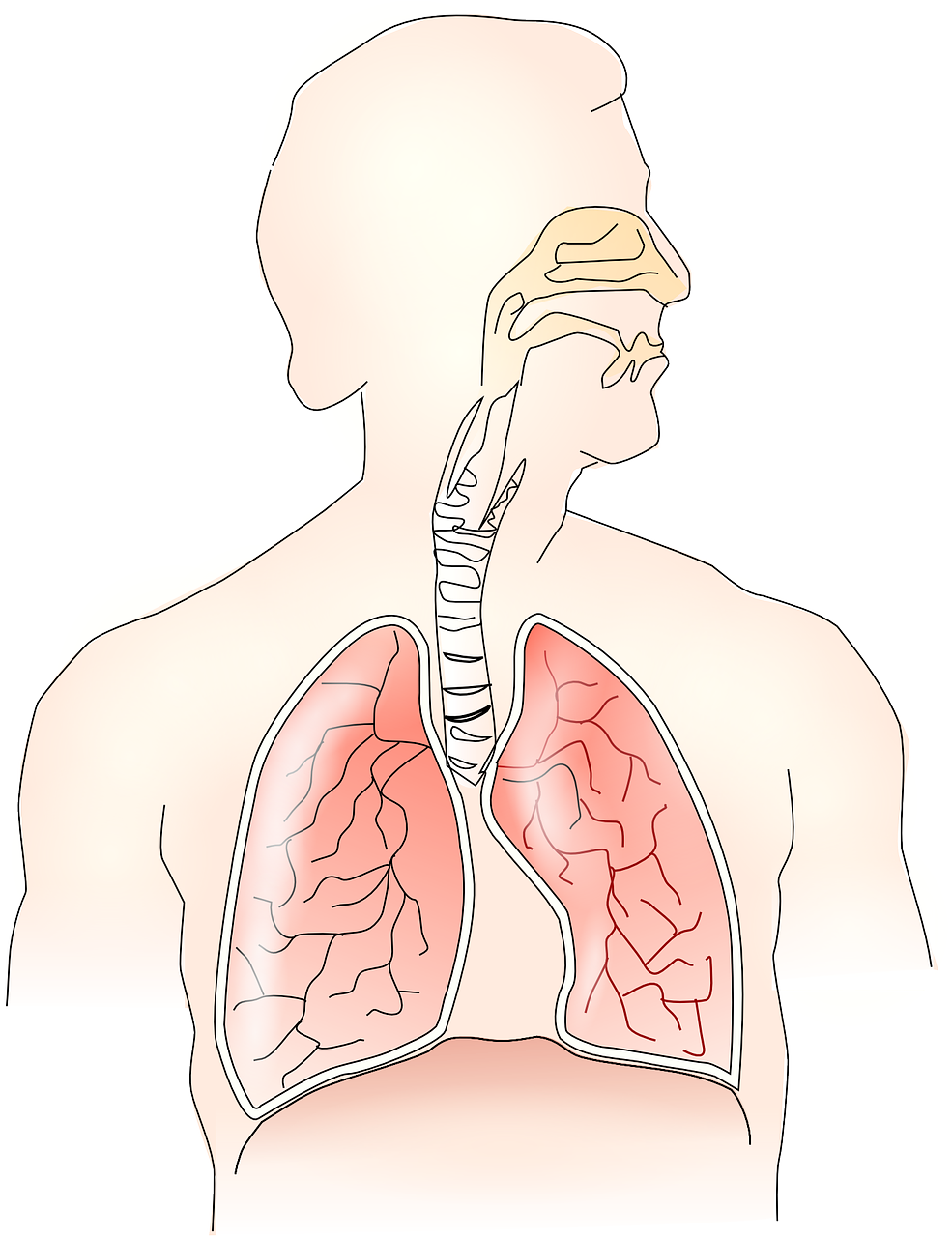

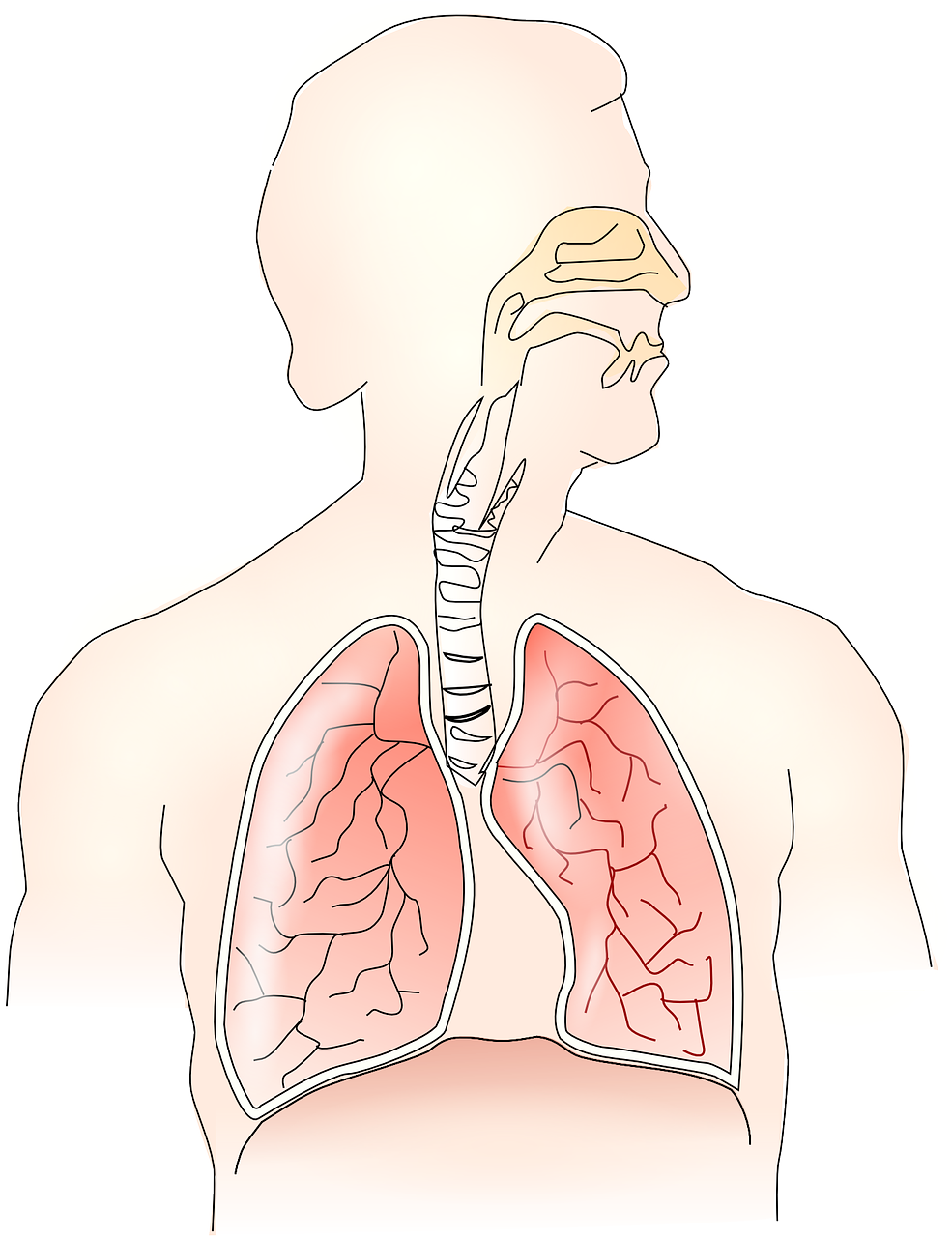

The respiratory system is essential to human survival, regulating gas exchange (oxygen-carbon dioxide) in the body to balance acid and base tissue cells for normal function. However, damage to the respiratory system can cause a plethora of issuesâfrom asthma and bronchitis to oxidative stress that triggers the development of extra-respiratory manifestations like rheumatoid arthritis and cardiovascular disease. Therefore, the rise in respiratory illnesses over the last three decades years is highly concerning, especially as research fails to identify an exact cause for the increase in respiratory disease cases.

Many researchers, including those in this study, suggest an increase in environmental pollutants like pesticides may be responsible for the influx of respiratory diseases. Although numerous studies detail the impacts of direct occupational pesticide exposure on human health, very few investigate how pesticides contribute to respiratory illnesses along the pesticide supply chainâfrom manufacturing, transportation, and application to cleaning and handling. Additionally, the review details the impact pesticide applications have on nearby communities. Literature reviews like these are significant as it encompasses all previous research on a topic and establishes a platform for current research basis.

In September 2019, researchers searched the âPub Medâ and âWeb of Scienceâ online database to find peer-reviewed scientific articles that investigate the relationship between pesticide exposure and respiratory diseases. To identify which studies are eligible for inclusion in the review, researchers used a set list of criteria including classification of pesticides (e.g., group of organisms fought against, mode of action, chemical nature, physical state, and toxicity) and categories of commonly used pesticides.

This review details observations concerning the involvement of pesticides on human health, including exposure, at-risk individuals, poisonings, respiratory impacts, and action mechanisms on the respiratory system. Additionally, the review compares these generalities to respiratory diseases and manifestations historically associated with pesticide exposure.

In September 2019, researchers searched the âPub Medâ and âWeb of Scienceâ online database to find peer-reviewed scientific articles that investigate the relationship between pesticide exposure and respiratory diseases. To identify which studies are eligible for inclusion in the review, researchers used a set list of criteria including classification of pesticides (e.g., group of organisms fought against, mode of action, chemical nature, physical state, and toxicity) and categories of commonly used pesticides.

This review details observations concerning the involvement of pesticides on human health, including exposure, at-risk individuals, poisonings, respiratory impacts, and action mechanisms on the respiratory system. Additionally, the review compares these generalities to respiratory diseases and manifestations historically associated with pesticide exposure.

A plethora of studies finds a high positive correlation between pesticide exposure and various respiratory pathologies (asthma, COPD, lung cancer) and manifestations (coughing, allergic rhinitis, laryngeal irritation, wheezing, dyspnea[hyperventilating]).

Lung cancer has a positive association with the total number of days and intensity of pesticide exposure. Prolonged exposure (over 56 days) to the insecticide chlorpyrifos more than doubles the risk of developing lung cancer. The insecticide diazinon also shows a strong correlation between exposure and lung cancer incidences. Additionally, normal to high exposure to the herbicide metolachlor and high levels of exposure to the herbicide pendimethalin increase the risk of developing lung cancer. More than 109 days of carbofuran exposure, one of the most toxic carbamate pesticides, leads to a 3-fold increase in lung cancer incidences. Intensive exposure to the herbicide dicamba, even at low levels, increases lung cancer incidence. Occupational exposure to chlorophenol-related compound (a group of pesticides contaminated with the highly toxic chemical dioxin) during the manufacturing process has a strong association with lung cancer. Chemicals with a weak but a positive association with lung cancer are malathion, atrazine, coumaphos, S-ethyl-N, N-dipropylthiocarbamate, alachlor, trifluralin, and chlorothalonil.

The risk of asthma incidences is seasonal with the spring having greater incidences due to the influx of pesticide use during the springtime. Moreover, those handling pesticides without protective equipment have a much greater risk of developing asthma after exposure. Pesticides that can cause laryngeal and bronchial spasm are primarily organophosphates and carbamates and are known to cause asthmatic episodes.

The review also finds a positive association between sarcoidosis development (a rare disease that causes a group of immune cells to form lumps) and occupational exposure to pesticides. Furthermore, the risk of developing Farmerâs lungâa common allergic disease induced by inhaling biological dust, and a contributor to respiratory morbidity among farmersâincreases with exposure to pesticides. These pesticides include dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, lindane, and aldicarb, as well as organochlorine and carbamate pesticides.

The review finds an association between deteriorating lung function and exposure to organophosphorus and carbamate insecticides, alongside other pesticides. Carbamate and organophosphorus insecticides are cholinesterase inhibitors that catalyze the decomposition of select neurotransmitters. Organophosphorus insecticides exposureâeven at low levelsâcan increase pro-inflammatory cytokine production leading to chronic inflammation that alters respiratory function and causes pulmonary fibrosis. Additionally, exposures to organophosphorus and carbamate pesticides have a significant association with both obstructive and restrictive respiratory anomalies. Chlorpyrifos, diazinon, dichlorvos, and malathion, in addition to carbaryl and permethrin, can increase the risk of allergic rhinitis. Furthermore, exposure to glyphosate herbicides and petroleum oil may cause the recurrence of rhinitis episodes.

Common respiratory manifestations among occupational exposure to pesticides are dyspnea, coughing, and expectoration, with coughing being significantly higher in agricultural workers than nonagricultural. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, including dimethoate, malathion, benomyl, mancozeb, and aldicarb, are the cause of many respiratory manifestations. Occupational and nonoccupational exposure to fumigants, such as methyl bromide, can cause respiratory manifestations (e.g., dyspnea, cough, respiratory irritation, and pulmonary lesions) in conjunction with local or systemic systems like fatigue, headache, dizziness, vomiting, abdominal pain, seizures, and impairment of the function of other organs.

Nonoccupational exposure to pesticides from residencies near pesticide processing plants, contact with pesticide-tainted clothes and tools, and household with improper storage and use of pesticides are at greater risk of respiratory illness, including asthma (ranking first) from chronic exposure, and upper and lower airway obstruction from acute exposure.

Lastly, the manipulation of pesticide mixtures has a strong association with dermal and respiratory systems, increasing oxidative stress biomarkers. Respiratory retailers are eight-fold more likely to experience respiratory distress than the general population, especially for retailers that sell manipulated organophosphorus compounds.

The connection between pesticides and associated respiratory risks is nothing new, as a plethora of studies links pesticide use and residue to various respiratory illnesses. Organophosphate pesticides like chlorpyrifos and carbamate pesticides like carbofuran have the most influence on respiratory pathology. Both chemical classes have a similar mode of action as cholinesterase inhibitors, which means that they bind to receptor sites for the enzyme acetylcholinesterase, or AChE, which is essential to normal nerve impulse transmission. In binding to those receptor sites, cholinesterase inhibitors inactivate AChE and preventing the clearing of acetylcholine. The buildup of acetylcholine can lead to acute impacts, such as uncontrolled, rapid twitching of some muscles, paralyzed breathing, convulsions, and, in extreme cases, death. The compromise of neural transmission can have broad systemic impacts on the function of multiple body systems.

Chlorpyrifos is an organophosate insecticide originating from World War II nerve agents. In addition to being highly toxic to terrestrial and aquatic organisms, human exposure to chlorpyrifos can induce endocrine disruption, reproductive dysfunction, fetal defects, neurotoxic damage, and kidney/liver damage. Although chlorpyrifos remains in use in the U.S., states, including Hawaii, California, New York, and Maryland, plan to phase out most of its agricultural use. This phasing out follows after the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) negotiated the chemical’s withdrawal from most of the residential market because of neurotoxic effects on children in 2000.

Carbofuran is an carbamate insecticide highly toxic to humans and other animals, killing birds that ingest only one pesticide-treated granule seed. This pesticide can cause nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and difficulty breathing. A 2009 action to cancel carbofuran food uses ultimately led to the chemical’s ban in the U.S., with EPA risk assessment finding no uses of carbofuran are eligible for reregistration due to its adverse impacts to humans and the environment. Unfortunately, as seen in Maryland, irresponsible and illegal use of pesticides is still responsible for primary and secondary poisonings of wildlife, as some farmers continue to use the poison illegally to kill larger predators and pests, including foxes, coyotes, and raccoons.

Although occupational exposure to both organophosphate and carbamate insecticides have adverse impacts in the respiratory system, these chemical classes also impact individuals non-occupationally, via pesticides drift or contamination. Communities adjacent to chemical-intensive farms or pesticide manufacturing plants experience higher levels of pesticide exposure than neighborhoods that are not. Furthermore, children living in homes near greenhouses which use these insecticides have abnormal nervous system function, including adverse pulmonary effects like asthma.

Previous studies document a significant association between pesticide exposure to chlorpyrifos and carbofuran and lung cancer. The connection between lung cancer and pesticides is of specific concern, as etiological studies often attribute lung cancer to genetics or cigarette smoke and overlook the lung cancer risks associated with pesticide exposure via inhalation of powders, airborne droplets, or vapors. Some studies attribute pesticidesâlabeled hazardous to inhaleâsprayed on tobacco plants to lung cancer and the related mechanisms that cause lung cancer. Upon inhalation, pesticide particles enter the respiratory tract, and the lungs readily absorb the particles into the bloodstream.

Working in close contact with pesticides throughout oneâs lifetime increases the risk of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and other respiratory issues like asthma. Just as lung cancer, etiological studies often attribute COPD risk to genetics or cigarette smoking, with cigarette smoke exposure causing eight out of ten cases of COPD. However, the increasing rate of COPD incidences indicates an external cause of COPD development besides the aforementioned risk factors, including poverty, dietary factors, and occupational exposure to chemicals like pesticides. Furthermore, studies find pesticide exposure not only triggers asthma attacks, but also causes asthma as exposure to insecticides before the age of five can increase in the risk of asthma diagnosis, with toddlers twice as likely to become asthmatic. Although significant disparities in asthma morbidity and mortality disproportionately impact low-income populations, people of color, and children living in inner cities, COPD has the potential to cause the same disparity in the future.

In the U.S., over 25 million people live with asthma, over 14 million individuals live with COPD, and millions of individuals live with lung cancer. The increasing rate of respiratory pathology, since the 1980s, demonstrates a need for better environmental policies and protocols surrounding contaminants like pesticides. Although EPA administers the Clean Air Act to regulate air pollution and reduce environmental contamination levels in the atmosphere, the Trump administration is dismantling many environmental regulations, putting air quality and human health at risk. Considering respiratory diseases represent a major health issue for agricultural workersâwho often experience pesticides exposure at higher rates due to occupationâit is essential to understand the association between pesticide exposure and respiratory pathology, or the study of causes and effects of respiratory diseases. Furthermore, with a new report finding an association between air pollution and higher death rates (9%) related to the outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19), global leaders must eliminate excessive pesticides use to mitigate the impacts respiratory diseases have on human health.

The connection between common and chronic respiratory diseases and exposure to pesticides continues to strengthen, despite efforts to restrict individual chemical exposure or mitigate chemical risks using risk assessment-based policy. Although the etiology of respiratory diseases encompasses several circumstances, including smoking patterns, poverty, occupation, and diet, studies show that relative exposure to chemicals like pesticides can occur within each circumstance, making chemical exposure ubiquitous. Additionally, pesticide drift is an omnipresent issue impacting communities surrounding farming operations, and dust may harm humans, plants, and aquatic systems.

It is vital to understand how exposure to pesticides can increase the risk of developing acute and chronic respiratory problems, especially if the Trump administrationsâ regulatory rollbacks increase the persistence of toxic chemicals in the environment. Beyond Pesticides tracks the most recent studies related to pesticide exposure through our Pesticide Induced Diseases Database (PIDD). This database supports the clear need for strategic action to shift away from pesticide dependency. For more information on the multiple harms of pesticide exposure, see PIDD pages on asthma/respiratory effects, cancer, endocrine disruption, and other diseases. Additionally, buying, growing, and supporting organic can help eliminate the extensive use of pesticides in the environment. Organic agriculture has many health and environmental benefits, which curtail the need for chemical-intensive agricultural practices. Regenerative organic agriculture revitalizes soil health through organic carbon sequestration while reducing pests and generating a higher return than chemical-intensive agriculture. For more information on how organic is the right choice for both consumers and the farmworkers who grow our food, see Beyond Pesticides webpage, Health Benefits of Organic Agriculture.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source(s): AAEM

(

(

(Beyond Pesticides, October 14, 2020) Exposure to certain endocrine disrupting pesticides increases the risk men, and Hispanic men in particular, will contract testicular cancer, according to research

(Beyond Pesticides, October 14, 2020) Exposure to certain endocrine disrupting pesticides increases the risk men, and Hispanic men in particular, will contract testicular cancer, according to research  (Beyond Pesticides, October 13, 2020)Â Â As the prestigious journal Nature publishes an article titled

(Beyond Pesticides, October 13, 2020)Â Â As the prestigious journal Nature publishes an article titled

(Beyond Pesticides, October 9, 2020)

(Beyond Pesticides, October 9, 2020)

(Beyond Pesticides, October 7, 2020) This week the Baltimore, Maryland City Council passed an ordinance restricting the use of toxic pesticides on public and private propertyâincluding lawns, playing fields, playgrounds, childrenâs facility (except school system property [golf courses are exempt]âfollowing an approach similar to legislation first spearheaded by

(Beyond Pesticides, October 7, 2020) This week the Baltimore, Maryland City Council passed an ordinance restricting the use of toxic pesticides on public and private propertyâincluding lawns, playing fields, playgrounds, childrenâs facility (except school system property [golf courses are exempt]âfollowing an approach similar to legislation first spearheaded by  (Beyond Pesticides, October 6, 2020) Despite the rapid rise of antibiotic resistance in the United States and throughout the world, new documents find the Trump Administration worked on behalf of a chemical industry trade group to weaken international guidelines aimed at slowing the crisis. Emails obtained by the Center for Biological Diversity through the Freedom of Information Act show that officials at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) worked to downplay the role of industrial agriculture and pesticide use in drug-resistant infections.

(Beyond Pesticides, October 6, 2020) Despite the rapid rise of antibiotic resistance in the United States and throughout the world, new documents find the Trump Administration worked on behalf of a chemical industry trade group to weaken international guidelines aimed at slowing the crisis. Emails obtained by the Center for Biological Diversity through the Freedom of Information Act show that officials at the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) worked to downplay the role of industrial agriculture and pesticide use in drug-resistant infections. (Beyond Pesticides, October 5, 2020)Â Â Another example of trading health and environmental protection for the support of special interests, EPA announces the misleading and fraudulently named, âEPA Supports Technology to Benefit America’s Farmers.â This time, EPA announces plans to âstreamline the regulation of certain plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs).â Named to sow confusion, PIPs are plants engineered with pesticides in them. PIPs are known in general for two problems arising from incorporating pesticidal ingredients into crops: residues that cannot be washed off and production of crop-eating insects that are resistant to the incorporated pesticide that blankets the agricultural landscape.Â

(Beyond Pesticides, October 5, 2020)  Another example of trading health and environmental protection for the support of special interests, EPA announces the misleading and fraudulently named, âEPA Supports Technology to Benefit America’s Farmers.â This time, EPA announces plans to âstreamline the regulation of certain plant-incorporated protectants (PIPs).â Named to sow confusion, PIPs are plants engineered with pesticides in them. PIPs are known in general for two problems arising from incorporating pesticidal ingredients into crops: residues that cannot be washed off and production of crop-eating insects that are resistant to the incorporated pesticide that blankets the agricultural landscape.  (Beyond Pesticides, October 2, 2020)Â

(Beyond Pesticides, October 2, 2020)Â  (Beyond Pesticides, September 30, 2020) Low doses of neonicotinoid (neonic) insecticides are known to disrupt insect learning and behavior, but new science is providing a better understanding of how these effects manifest at a cellular level. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, this study finds that the neonic imidacloprid binds to brain receptors, triggering oxidative stress, reducing energy levels, and causing neurodegeneration.

(Beyond Pesticides, September 30, 2020) Low doses of neonicotinoid (neonic) insecticides are known to disrupt insect learning and behavior, but new science is providing a better understanding of how these effects manifest at a cellular level. Published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, this study finds that the neonic imidacloprid binds to brain receptors, triggering oxidative stress, reducing energy levels, and causing neurodegeneration. (Beyond Pesticides, September 29, 2020) While the

(Beyond Pesticides, September 29, 2020) While the  (Beyond Pesticides, September 28, 2020) These comments are due by October 5 at 11:59 pm EDT.

(Beyond Pesticides, September 28, 2020) These comments are due by October 5 at 11:59 pm EDT.  (Beyond Pesticides, September 25, 2020)Â

(Beyond Pesticides, September 25, 2020)Â

(Beyond Pesticides, September 23, 2020) Multinational agrichemical corporation Bayer coordinated with the U.S. government to pressure Thailand to

(Beyond Pesticides, September 23, 2020) Multinational agrichemical corporation Bayer coordinated with the U.S. government to pressure Thailand to  (Beyond Pesticides, September 22, 2020) Use of the highly hazardous, endocrine disrupting weed killer atrazine is likely to expand following a decision made earlier this month by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Under the guise of âregulatory certainty,â the agency is reapproving use of this notorious herbicide, as well as its cousins simazine and propazine in the triazine family of chemicals, with fewer safeguards for public health, particularly young children. Advocates are incensed by the decision and vow to continue to put pressure on the agency. âUse of this extremely dangerous pesticide should be banned, not expanded,â Nathan Donley, PhD, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity saidÂ

(Beyond Pesticides, September 22, 2020) Use of the highly hazardous, endocrine disrupting weed killer atrazine is likely to expand following a decision made earlier this month by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Under the guise of âregulatory certainty,â the agency is reapproving use of this notorious herbicide, as well as its cousins simazine and propazine in the triazine family of chemicals, with fewer safeguards for public health, particularly young children. Advocates are incensed by the decision and vow to continue to put pressure on the agency. âUse of this extremely dangerous pesticide should be banned, not expanded,â Nathan Donley, PhD, a senior scientist at the Center for Biological Diversity said  (Beyond Pesticides, September 21, 2020) The National Organic Standards Board (NOSB)

(Beyond Pesticides, September 21, 2020)Â The National Organic Standards Board (NOSB)  (Beyond Pesticides, September 18, 2020)Â In late August,

(Beyond Pesticides, September 18, 2020)Â In late August,  (Beyond Pesticides, September 17, 2020) The apparel industry becomes the latest contributor to global biodiversity loss, directly linking soil degradation, natural ecosystems destruction, and environmental pollution with apparel supply chains, according to the report, â

(Beyond Pesticides, September 17, 2020) The apparel industry becomes the latest contributor to global biodiversity loss, directly linking soil degradation, natural ecosystems destruction, and environmental pollution with apparel supply chains, according to the report, â