(Beyond Pesticides, July 31, 2020)Â On July 22, the New York State Legislature passed Senate 6502 / Assembly 732-B â a bill that would ban the use of all glyphosate-based herbicides on state properties. The bill now awaits Governor Andrew Cuomoâs signature, which would make it law effective December 31, 2021. Beyond Pesticides considers this a hopeful development in the glyphosate âsagaâ and has urged the governor ought to sign it. Nevertheless, such piecemeal, locality-by-locality initiatives represent mere âdropsâ of protection in an ocean of toxic chemical pesticides to which the U.S. public is exposed. A far more effective, protective solution is the much-needed transition from chemical-intensive agriculture and other kinds of land management to organic systems that do not use toxic pesticides.

(Beyond Pesticides, July 31, 2020)Â On July 22, the New York State Legislature passed Senate 6502 / Assembly 732-B â a bill that would ban the use of all glyphosate-based herbicides on state properties. The bill now awaits Governor Andrew Cuomoâs signature, which would make it law effective December 31, 2021. Beyond Pesticides considers this a hopeful development in the glyphosate âsagaâ and has urged the governor ought to sign it. Nevertheless, such piecemeal, locality-by-locality initiatives represent mere âdropsâ of protection in an ocean of toxic chemical pesticides to which the U.S. public is exposed. A far more effective, protective solution is the much-needed transition from chemical-intensive agriculture and other kinds of land management to organic systems that do not use toxic pesticides.

The bill â titled âAn Act to amend the environmental conservation law, in relation to prohibiting the use of glyphosate on state propertyâ â was introduced in 2019 and sponsored by New York State Assembly Member Linda B. Rosenthal (D/WF-New York) and State Senator JosĂ© Serrano. It would add a new subdivision to section 12 of the stateâs environmental conservation law, proscribing âany state department, agency, public benefit corporation or any pesticide applicator employed thereby as a contractor or subcontractor to apply glyphosate on state property.â More than 50,000 gallons of glyphosate-based herbicides were applied in public spaces across the entirety of the state, as reported in 2019 by Bronx.com.

Senator Serrano said of the bill, âOur parks, playgrounds and picnic areas are an oasis for New Yorkers, and have particularly become safe havens during the COVID-19 pandemic. It is important that we protect the health and safety of workers, families, and pets by proactively eliminating the use of potentially harmful chemicals like glyphosate in our public spaces, and by finding safe alternatives that will not risk the health of New Yorkers and our environment.â

Assembly Member Rosenthal commented: âWeeds are unsightly, but cancer is a killer, and we should not wait for a child or anyone to become sick to take action to protect them against a serious potential risk. Parents donât want their children exposed to dangerous, toxic chemicals when they play in state parks, and groundskeepers and farm workers should not be exposed to potentially deadly chemicals while doing their job. Prohibiting the use of glyphosate on State property makes good sense: doing so will protect the public health and environment while shielding the State from millions of dollars in potential liability associated with its use. With safer alternatives available, there is no reason the State should be using a potential carcinogen to kill weeds.â

Glyphosate is the active ingredient in the herbicide RoundupTM, Monsantoâs (now Bayerâs) ubiquitous and widely used weed killer; it is very commonly used with Monsantoâs companion seeds for a variety of staple crops (e.g., soybeans, cotton, corn, canola, and others). These glyphosate-tolerant seeds are genetically engineered to be glyphosate tolerant; growers apply the herbicide and expect that it will kill weeds and not harm the crop. Roundup has been marketed as effective and safe, but, in reality, its use delivers human and ecosystem harms. Exposures to it threaten human health (including transgenerational impacts) and the health of numerous organisms. In addition, many target plants are developing resistance to the compound, making it increasingly ineffective as a weed killer, and resulting in ever-more-intensive pesticide use. Glyphosate was classified in 2015 by the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) as a probable human carcinogen.

Because children spend ample time in and on the kinds of turf that are often treated with glyphosate, and are more likely than adults to inhale, or ingest, or incur other kinds of exposures from grass and soil, Beyond Pesticides and many experts are very concerned about the use of this toxic chemical on such sites. Indeed, a study by the Center for Environmental Health found that children carry significantly higher levels of glyphosate in their bodies than do their parents.

Legislative and regulatory moves on the parts of states, counties, cities, and towns, like this bill in New York State: (1) happen in the context of, and in part because of, the Trump administrationâs Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) abdication of its protective responsibility to the public; (2) are often successfully challenged on the grounds that âhigher levelâ pre-emption supersedes local laws and regulations; and (3) tackle the problem one chemical compound in one locality at a time â an approach that Beyond Pesticides Executive Director Jay Feldman has called âwhack-a-mole.â

In addition, federal pesticide regulations in the Trump era have intentionally been made less robust and narrower in scope, and enforcement even of those has been anemic. That said, for decades, EPA has for decades aimed to âmitigateâ risks rather than exercise the principle of Precaution in rulemaking. In July 2020, Beyond Pesticides described âthe folly of the federal regulatory systemâs attempts to âmitigateâ risks of pesticide exposure through small and piecemeal rules. Given the many thousands of chemical pesticides on the market, the complexity of trying to ensure ârelativeâ safety from them (especially considering potential synergistic interactions, as well as interactions with genetic and âlifestyleâ factors), and the heaps of cash that fund corporate interests . . . via lobbyists and trade associations, there is one conclusion. âMitigationâ of pesticide risks is a nibble around the edges of a pervasive poison problem.â All of these failings have been made worse by an administration devoted to reducing or eliminating regulation on corporate actors.

There is no guarantee that Governor Cuomo will sign Senate 6502 / Assembly 732-B into law; in early 2020, he vetoed legislation to ban chlorpyrifos, and instead issued an immediate ban on aerial application, and proposed a regulatory phase-out to ban all uses by 2021. As the chief executive official of the state, he could â In addition to signing bills that come from the Legislature â take executive action to, for example, ban use of the most dangerous pesticides. Beyond Pesticides believes that the governor is not living up to his responsibility to protect the safety and well-being of New York State residents and environment from the dangers of chemical pesticides.

Beyond Pesticides reported on a bill for a local law proposed in 2019 in New York City Council (Intro 1524) that would prohibit city agencies from applying any chemically based pesticide to any property owned or leased by the City of New York. In 2019, Bronx.com reports, the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation used upward of 500 gallons of glyphosate on 28,000+ acres of parks, playgrounds, beaches, athletic fields, recreational facilities, and other sites to âcontrolâ weeds. In its January 2020 hearing before the councilâs Committee on Health, the bill was ultimately âlaid over by committeeâ â a term that can mean a bill will be taken up the next legislative day, but which also can be a euphemism for âhow a bill gets killed by ignoring it.â

In covering that bill, Beyond Pesticides wrote about the context in which New York City and other localities have increasingly turned to local action: âThe issue is made more urgent, for New York City and for many, many municipalities and states, because most environmental regulation below the federal level in the U.S relies heavily on the determinations of EPA. Under the Trump administration, federal environmental regulation generally, and regulation of pesticides, in particular, have been dramatically weakened; this administration and its EPA clearly advantage agrochemical and other industry interests over the health of people and ecosystems. The consequent loss of public trust in federal agencies broadly, and EPA in particular, reinforce the need for localities to step up and protect local and regional residents and environments.â Currently, the bill is being held up by the Speakerâs office.

Along with the bill banning use of glyphosate on state property, the New York State Legislature passed S.5579a / A.5169, which, when signed, will mandate that written notices and signs informing the public of pesticide use in commercial and residential settings be printed in English, Spanish, and any other locally relevant languages. Senator Serrano commented, âItâs critical that all New Yorkers are aware of any warnings regarding pesticide use and application in their neighborhoods. . . . [This bill will ensure] that every resident can be adequately informed of pesticide use in their communities and take steps to ensure the health and safety of their loved ones.â

In light of the increasing evidence of the harm glyphosate can cause, some countries have stepped up restrictions or instituted bans on use of the compound, including Italy, Germany, France, Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Bermuda, Fiji, Luxembourg, and Austria. A growing number of jurisdictions in some countries have taken similar actions. In the U.S., counties, towns, and cities, including Los Angeles, Seattle, and Miami, and many others in California, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, Washington State, and more, have banned glyphosate applications on public lands.

Beyond Pesticides urges a federal ban on the use of glyphosate herbicides, and supports interim efforts of localities to protect their own communities â and those who work directly with these chemical â as New York State is beginning to do through this bill (S.6502 / A.732-B) that would prohibit glyphosate use on all state properties. It is unfortunate that, if signed, the law would not go into effect until the very last day of 2021, but Governor Cuomo should nevertheless immediately sign the bill into law.

The solution to the current federal âwhack-a-moleâ approach to mitigating the impacts of glyphosate (and all pesticide) use is a wholesale transition away from the chemical dousing of public lands, agricultural fields, and all manner of maintained turf. Organic approaches to pest and weed problems in agriculture and on other lands and landscapes (and in homes, gardens, buildings, et al.) do not involve toxic pesticides, and avoid the health and ecological damage they cause.

In addition to being genuinely protective of human health, organic management systems support biodiversity, improve soil health, sequester carbon (which helps mitigate the climate crisis), and safeguard surface- and groundwater quality. Beyond Pesticides encourages the public to contact federal, state, and local officials to demand real protection from toxic pesticides, perhaps beginning with a ban on the use of glyphosate on public lands, as New York is attempting to do. Find contact information for federal Representatives here, and for Senators here. Contact information for states and localities is typically available on state and city/town websites.

Source: https://bronx.com/new-york-state-poised-to-ban-use-of-glyphosate-on-state-land/

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

(Beyond Pesticides, August 18, 2020) Ongoing declines in bird population and diversity are being accelerated by the use of neonicotinoid insecticides, according to research published in Nature Sustainability earlier this month. The paper comes on the heels of a groundbreaking study released last year, finding that the United States has lost 3 billion birds since 1970, a roughly 30% decrease from that time. This new research adds further detail to losses that have occurred within the last decade, as farming patterns have shifted increasingly to the use of pesticide-coated seeds that poison.

(Beyond Pesticides, August 18, 2020) Ongoing declines in bird population and diversity are being accelerated by the use of neonicotinoid insecticides, according to research published in Nature Sustainability earlier this month. The paper comes on the heels of a groundbreaking study released last year, finding that the United States has lost 3 billion birds since 1970, a roughly 30% decrease from that time. This new research adds further detail to losses that have occurred within the last decade, as farming patterns have shifted increasingly to the use of pesticide-coated seeds that poison.

(Beyond Pesticides, August 17, 2020)Â Once numbering in the millions, barely 29,000 western monarch butterflies were found in California at last count. Pesticides pack a one-two punch against monarchs. Insecticidesâparticularly neonicotinoidsâpoison the caterpillars and butterflies as they feed. Glyphosateâthe active ingredient in Bayer-Monsanto’s RoundupÂź â is wiping out milkweed, the only food source for monarch caterpillars. This has contributed to monarchs’ 90% decline in the past 20 years alone. They could vanish within our lifetimes.

(Beyond Pesticides, August 17, 2020)Â Once numbering in the millions, barely 29,000 western monarch butterflies were found in California at last count. Pesticides pack a one-two punch against monarchs. Insecticidesâparticularly neonicotinoidsâpoison the caterpillars and butterflies as they feed. Glyphosateâthe active ingredient in Bayer-Monsanto’s RoundupÂź â is wiping out milkweed, the only food source for monarch caterpillars. This has contributed to monarchs’ 90% decline in the past 20 years alone. They could vanish within our lifetimes. (Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2020)Â Levels of the notorious herbicide compound

(Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2020)Â Levels of the notorious herbicide compound  (Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2020) An alarming new scientific report finds that excessive, indiscriminate disinfectant use against COVID-19 puts wildlife health at risk, especially in urban settings. The analysis, published in the journalÂ

(Beyond Pesticides, August 13, 2020) An alarming new scientific report finds that excessive, indiscriminate disinfectant use against COVID-19 puts wildlife health at risk, especially in urban settings. The analysis, published in the journal  (Beyond Pesticides, August 12, 2020) The herbicide atrazine can interfere with the health and reproduction of marsupials (including kangaroos and opossums)

(Beyond Pesticides, August 12, 2020) The herbicide atrazine can interfere with the health and reproduction of marsupials (including kangaroos and opossums)

(Beyond Pesticides, August 10, 2020) As parents, educators, and administrators decide whether to open schools with in-person teaching, there are escalating concerns about the ability of schools to put in place the programs necessary to protect the health of students, staff, and their families from coronavirus (COVID-19). A key part of most school reopening plans is the fogging or misting of classrooms with toxic disinfectants, raising questions about safe and effective disinfection and sanitizing practices, in addition to social practices that public health officials have advised, to prevent transmission of the virus.

(Beyond Pesticides, August 10, 2020) As parents, educators, and administrators decide whether to open schools with in-person teaching, there are escalating concerns about the ability of schools to put in place the programs necessary to protect the health of students, staff, and their families from coronavirus (COVID-19). A key part of most school reopening plans is the fogging or misting of classrooms with toxic disinfectants, raising questions about safe and effective disinfection and sanitizing practices, in addition to social practices that public health officials have advised, to prevent transmission of the virus. (Beyond Pesticides, August 7, 2020) Research out of the Silent Spring Institute

(Beyond Pesticides, August 7, 2020) Research out of the Silent Spring Institute  (Beyond Pesticides, August 6, 2020) New research finds that a decline in wild pollinator abundance, notably wild bees, limits crop yields in the U.S., according to the study, â

(Beyond Pesticides, August 6, 2020) New research finds that a decline in wild pollinator abundance, notably wild bees, limits crop yields in the U.S., according to the study, â (Beyond Pesticides, August 5, 2020) Regions of Australia that use a highly toxic rodenticide are home to larger dingoes than areas where the pesticide is not used, according to research published in the

(Beyond Pesticides, August 5, 2020) Regions of Australia that use a highly toxic rodenticide are home to larger dingoes than areas where the pesticide is not used, according to research published in the  (Beyond Pesticides, August 4, 2020) Last month Massachusetts lawmakers finalized, and the Governor subsequently signed,

(Beyond Pesticides, August 4, 2020) Last month Massachusetts lawmakers finalized, and the Governor subsequently signed,  (Beyond Pesticides, August 3, 2020)Â The effects of pesticide use are important, yet ignored, factors affecting people of color (POC) who face elevated risk from Covid-19 as essential workers, as family members of those workers, and because of the

(Beyond Pesticides, August 3, 2020)Â The effects of pesticide use are important, yet ignored, factors affecting people of color (POC) who face elevated risk from Covid-19 as essential workers, as family members of those workers, and because of the  (Beyond Pesticides, July 31, 2020)Â On July 22, the New York State Legislature passed

(Beyond Pesticides, July 31, 2020)Â On July 22, the New York State Legislature passed  (Beyond Pesticides, July 30, 2020) Simultaneous exposure to pesticides and noise from agricultural machinery increases farmworkers, risk of hearing loss, according to the study, â

(Beyond Pesticides, July 30, 2020) Simultaneous exposure to pesticides and noise from agricultural machinery increases farmworkers, risk of hearing loss, according to the study, â (Beyond Pesticides, July 29, 2020) Farmworkers and landscapers are deemed essential employees during the coronavirus outbreak, but without mandated safety protocols or government assistance, have experienced an explosion in Covid-19 cases. Workers in these industries are primarily Latinx people of color, many of whom are undocumented. According to a

(Beyond Pesticides, July 29, 2020) Farmworkers and landscapers are deemed essential employees during the coronavirus outbreak, but without mandated safety protocols or government assistance, have experienced an explosion in Covid-19 cases. Workers in these industries are primarily Latinx people of color, many of whom are undocumented. According to a  (Beyond Pesticides, July 28, 2020) With honey bees around the world under threat from toxic pesticide use, researchers are investigating a new way to track environmental contaminants in bee hives. This new product, APIStrip (Adsorb Pesticide In-hive Strip), can be placed into bee hives and act as a passive sampler for pesticide pollution. Honey bees are sentinel species for environmental pollutants, and this new technology could provide a helpful way not only for beekeepers to pinpoint problems with their colonies, but also track ambient levels of pesticide pollution in a community.

(Beyond Pesticides, July 28, 2020) With honey bees around the world under threat from toxic pesticide use, researchers are investigating a new way to track environmental contaminants in bee hives. This new product, APIStrip (Adsorb Pesticide In-hive Strip), can be placed into bee hives and act as a passive sampler for pesticide pollution. Honey bees are sentinel species for environmental pollutants, and this new technology could provide a helpful way not only for beekeepers to pinpoint problems with their colonies, but also track ambient levels of pesticide pollution in a community. (Beyond Pesticides, July 27, 2020)

(Beyond Pesticides, July 27, 2020)  (Beyond Pesticides, July 24, 2020)Â As the novel coronavirus pandemic has heightened awareness of infectious diseases, there is increased attention to connections between environmental concerns and such diseases, including factors that may exacerbate their transmission.

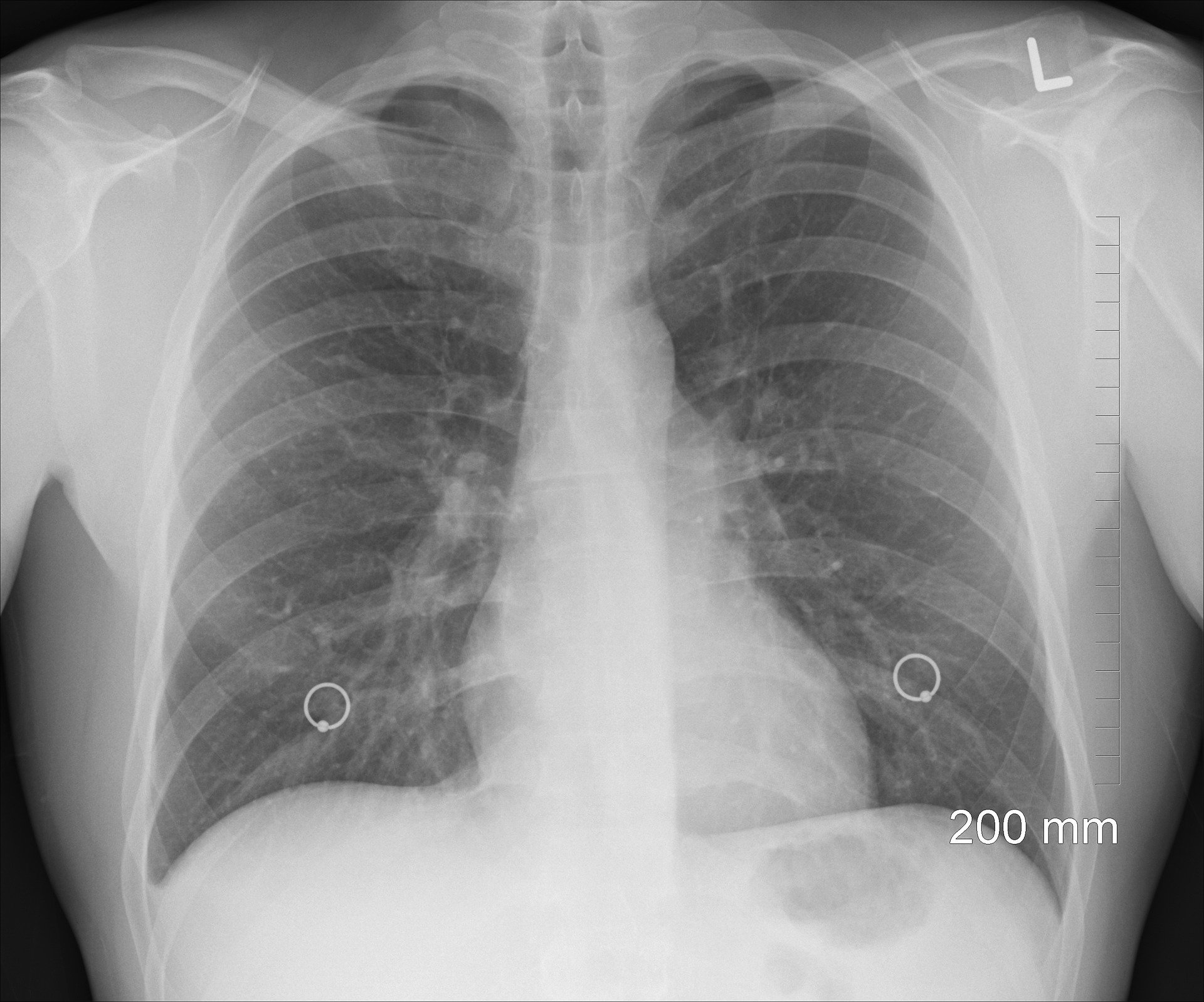

(Beyond Pesticides, July 24, 2020)Â As the novel coronavirus pandemic has heightened awareness of infectious diseases, there is increased attention to connections between environmental concerns and such diseases, including factors that may exacerbate their transmission.  (Beyond Pesticides, July 23, 2020) Chronic pesticide use, and subsequent exposure, elevate a personâs risk of developing lung cancer, according to a study published inÂ

(Beyond Pesticides, July 23, 2020) Chronic pesticide use, and subsequent exposure, elevate a personâs risk of developing lung cancer, according to a study published in  (Beyond Pesticides, June 22, 2020) In the latest issue of

(Beyond Pesticides, June 22, 2020) In the latest issue of  (Beyond Pesticides, July 21, 2020) Climate change and pesticide pollution are known to put coral reef fish at significant risk, but research published in

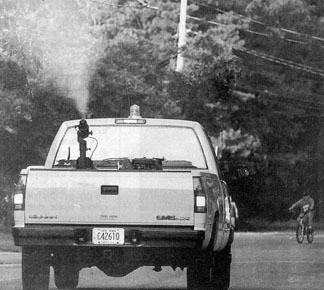

(Beyond Pesticides, July 21, 2020) Climate change and pesticide pollution are known to put coral reef fish at significant risk, but research published in  (Beyond Pesticides, July 20, 2020) Does your community spray toxic pesticides for mosquitoes? In a well-intentioned but ill-informed attempt to prevent mosquito-borne illness such as West Nile virus, many communities spray insecticides (adulticides) designed to kill flying mosquitoes. If your community is one of these, then your public officials need to know that there is a better, more-effective, way to prevent mosquito breeding.

(Beyond Pesticides, July 20, 2020) Does your community spray toxic pesticides for mosquitoes? In a well-intentioned but ill-informed attempt to prevent mosquito-borne illness such as West Nile virus, many communities spray insecticides (adulticides) designed to kill flying mosquitoes. If your community is one of these, then your public officials need to know that there is a better, more-effective, way to prevent mosquito breeding.