25

Nov

Hormone Mimicking Properties of Glyphosate Weed Killer and Related Compounds Increase Breast Cancer Risk

(Beyond Pesticides, November 25, 2022) A study published in Chemosphere adds to the growing body of research demonstrating the endocrine (hormone) disrupting effects of glyphosate play in breast cancer development. Exposure to the herbicide glyphosate and other glyphosate-based herbicides (GBHs) at high concentrations mimics the estrogen-like cellular effects of 17ÎČ-estradiol (E2), altering binding activity to estrogen receptor α (ERα) sites, thus causing fundamental changes in breast cancer cell proliferation (abundance).Â

Glyphosate is the most commonly used active ingredient worldwide, appearing in many herbicide formulas, not just Bayerâs (formerly Monsanto) RoundupÂź. The use of this chemical has been increasing since the inception of crops genetically modified to tolerate glyphosate over two decades ago. The toxic herbicide readily contaminates the ecosystem with residues pervasive in food and water commodities. In addition to this study, literature proves time and time again that glyphosate has an association with cancer development, as well as human, biotic, and ecosystem harm. Therefore, advocates point to the need for national policies to reassess hazards associated with disease development and diagnosis upon exposure to chemical pollutants. The researchers note, âThe results obtained in this study are of toxicological relevance since they indicate that glyphosate could be a potential endocrine disruptor in the mammalian system. Additionally, these findings suggest that glyphosate at high concentrations may have strong significance in tamoxifen resistance and breast cancer progression. [F]urther studies in animal models must confirm these effects on organ systems.â

The study evaluated the cytotoxic (toxic to cells) effect of analytical grade glyphosate and GBHs to evaluate its estrogenic activity. The literature shows that significant exposure to these GBHs can cause cell death from the active ingredient glyphosate, as well as other ingredients in the formulations. These ingredients can have detergent-like properties (e.g., adjuncts) that can amplify the cytotoxic effects of glyphosate. The researchers aim to clarify the molecular mechanism involved in glyphosate-induced estrogen production and breast cancer cells. The Chilean researchers in the study find exposure to glyphosate at high concentrations induces estrogen-like effects through binding to estrogen receptor α (ERα) sites, mimicking the cell effects of 17ÎČ-estradiol (E2), attaching a phosphate group to the zinc (Zn) II ion (phosphorylation), thus causing fundamental changes to estrogen in breast cancer cells. Like past studies, this study demonstrates that glyphosate mimics the effect of E2 through Erα phosphorylation.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women, causing the second most cancer-related deaths in the United States. Past studies suggest genetic inheritance factors influence breast cancer occurrence. However, genetic factors only play a minor role in breast cancer incidents, while exposure to external environmental factors (i.e., chemical exposure) may play a more notable role. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), breast cancer is a disease that causes breast cells to grow out of control, with the type of breast cancer depending on the cells themselves. Most common forms of breast cancer have receptors on the cell surface that can increase cancer growth when activated by estrogen, progesterone, or too much of the protein called HER2. Hormones generated by the endocrine system greatly influence hormone cancer incidents among humans (e.g., breast, prostate, and thyroid cancers). Several studies and reports, including U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) data, identify hundreds of chemicals as influential factors associated with breast cancer risk. One in ten women will receive a breast cancer diagnosis, and genetics can only account for five to ten percent of cases. There are grave concerns over exposure to endocrine (hormone) disrupting chemicals and pollutants that produce adverse health effects. Considering not only glyphosate but over 296 chemicals in consumer products can increase breast cancer risk through endocrine disruption, it is essential to understand how chemical exposure impacts chronic disease occurrence.Â

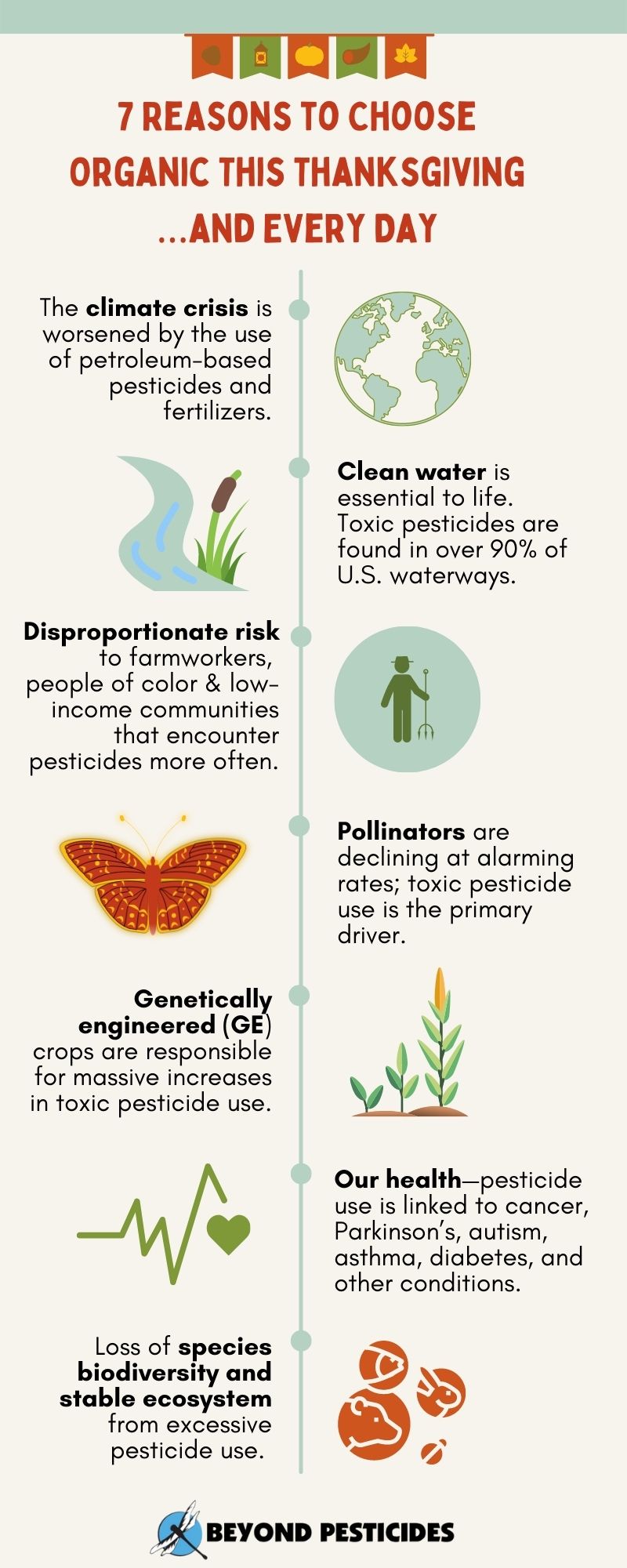

Glyphosate has been the subject of a great deal of public advocacy and regulatory attention and is the target of thousands of lawsuits. Beyond Pesticides has covered the glyphosate tragedy extensively; see its litigation archives for multiple articles on glyphosate lawsuits. Almost five decades of extensive glyphosate-based herbicide use has put human, animal, and environmental health at risk. The chemical’s ubiquity threatens 93 percent of all U.S. endangered species, resulting in biodiversity loss and ecosystem disruption (e.g., soil erosion and loss of services). Exposure to GBHs can cause specific alterations in microbial gut composition and trophic cascades. Similar to this paper, past studies find a strong association between glyphosate exposure and the development of various health anomalies, including cancer, Parkinson’s disease, and autism. The risk assessment process used by EPA for its pesticide registration process is substantially inadequate to protect human health. Although EPA classifies glyphosate herbicides as “not likely to be carcinogenic to humans, “stark evidence demonstrates links to various cancers, including non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Moreover, EPA fails to adequately consider exposure effects on mammary gland development in its review of animal studies related to pesticide impacts. Thus, EPA’s classification perpetuates environmental injustice among individuals disproportionately exposed to chemicals, like farmworkers, especially in marginalized communities.

Several studies link pesticide use and residue to various cancers, from more prevalent forms like breast cancer to rare ones like kidney cancer nephroblastoma (Wilmsâ tumor). Although the connection between pesticides and associated cancer risks is nothing new, past studies suggest glyphosate and GBHs act as endocrine disruptors, affecting the development and regulation of estrogen hormones that promote breast cancer. However, this study is one of the few to evaluate the molecular mechanisms involved in toxicological changes initiating breast cancer events. Phosphorylation with a Zn (II) ion stabilized the bond between the estrogen-imitating activity of glyphosate and GBHs to the Erα. Therefore, the bond promotes the overexpression of estrogen-sensitive genes, increasing consequences on breast cancer cell activity. The study concludes, âThe results obtained in this study are of toxicological relevance since they indicate that glyphosate could be a potential endocrine disruptor in the mammalian system. â

Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide. Much pesticide use and exposure are associated with cancer effects. Studies concerning pesticides and cancer help future epidemiologic research understand the underlying mechanisms that cause cancer. Although the link between agricultural practices and pesticide-related illnesses is stark, over 63 percent of commonly used lawn pesticides and 70 percent of commonly used school pesticides have links to cancer. Advocates argue that global leaders must fully understand the cause of pesticide-induced diseases before the chemicals enter the environment. Policy reform and practices that eliminate toxic pesticide use can end the uncertainty surrounding potential harm. For more information on the harms of pesticides, see Beyond Pesticidesâ Pesticide-Induced Diseases Database pages on breast cancer, endocrine disruption, and other diseases. This database supports the need for strategic action to shift away from pesticide dependency.

Prevention of the causes of breast cancer, not just awareness, is critical to solving this disease. In 1985, Imperial Chemical Industries and the American Cancer Society declared October âBreast Cancer Awareness Monthâ as part of a campaign to promote mammograms for the early detection of breast cancer. Unfortunately, most people are all too aware of breast cancer. Detection and treatment of cancers do not solve the problem. EPA should evaluate and ban endocrine-disrupting pesticides and make organic food production and land management the standard that legally establishes toxic pesticide use as âunreasonable.â

Moreover, proper prevention practices, like buying, growing, and supporting organics, can eliminate exposure to toxic pesticides. Organic agriculture has many health and environmental benefits that curtail the need for chemical-intensive agricultural practices. Regenerative organic agriculture nurtures soil health through organic carbon sequestration while preventing pests and generating a higher return than chemical-intensive agriculture. For more information on how organic is the right choice, see the Beyond Pesticides webpage, Health Benefits of Organic Agriculture.Â

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: ChemosphereÂ