(Beyond Pesticides, April 12, 2023) Spring represents a period of increased water, soil, and general ecosystem pollution, correlated with increased pesticide use and increased rainfall. Thus, April showers bring May flowers, and often pesticides. We offer this overview to share with friends, family, and your community in an effort to elevate the urgent need to eliminate pesticides and make the shift to organic land management.

Pesticides are pervasive in the environment, affecting all ecosystems, including air, water, and soil. Like clean air and water, healthy soils are integral to ecosystem function, interacting between Earth’s four main spheres (i.e., hydrosphere, biosphere, lithosphere, and atmosphere) to support life. Pesticide use results in pervasive contamination of treated and nontarget sites. Even organic farmers and gardeners globally suffer from the widespread movement of pesticides through the air, water, and runoff from land. Attempts to protect property and ecosystems from pesticide use are a difficult, some say impossible, challenge. Efforts to prevent contamination become a large burden, with attempts to curtail pesticide drift with buffer zone areas and eliminate fertilizers or soil supplements with pesticide residues (e.g., manure and compost). Furthermore, the effects of climate change only exacerbate threats to ecosystem health, as studies show a link between the global climate emergency and the adverse impacts of pesticide exposure.

However, organic land management in agriculture and parks, playing fields, and landscapes offer the only real alternative for meaningful protection of those who work the land (farmworkers, farmers, landscapers, and gardeners) and all who eat food, drink water and breathe air. Additionally, the adoption of organic methods, particularly no-till organic, is an opportunity for farming both to mitigate agriculture’s contributions to climate change and to cope with the effects climate change has had and will have on agriculture. Research from the Rodale Instituteâs Farming Systems TrialÂź (FST) has revealed that organic, regenerative agriculture actually has the potential to lessen the impacts of climate change. This occurs through the drastic reduction in petrochemical pesticide and fertilizer usage to produce the crops (approximately 75% less fertilizer use overall than chemical-intensive agriculture) and a significant increase in carbon sequestration in the soil. Most importantly, no-till organic methods produce comparable yields to conventional systems on average, and higher yields in drought years because of the greater water-holding capacity of the organic soils. Therefore, organic land management is not only necessary to eliminate the use of toxic chemicals but also to ensure the long-term sustainability of our land and ecosystems.

Prepare Your Spring Gardens without Synthetics.

Growing your own food can be a transformative experience. Whether you live in the city and only have room for a few window pots of herbs, or you have enough space to set up a backyard garden to provide nearly all your produce needs, growing your own food organically is worth a try. Planting organic seeds and plants can ensure a pesticide-free garden, since plants in garden centers are often grown from seeds coated with toxic fungicides, bee-harming insecticides like neonicotinoids (neonics), or drenched with them.

Eliminate Synthetic Chemicals.

Synthetic petrochemical fertilizers and pesticides lead to undesirable conditions that restrict water and air movement in the soil. High-nitrogen fertilizers can disrupt the nutrient balance, accelerate turf growth and increase the need for mowing, while contributing to thatch buildup.

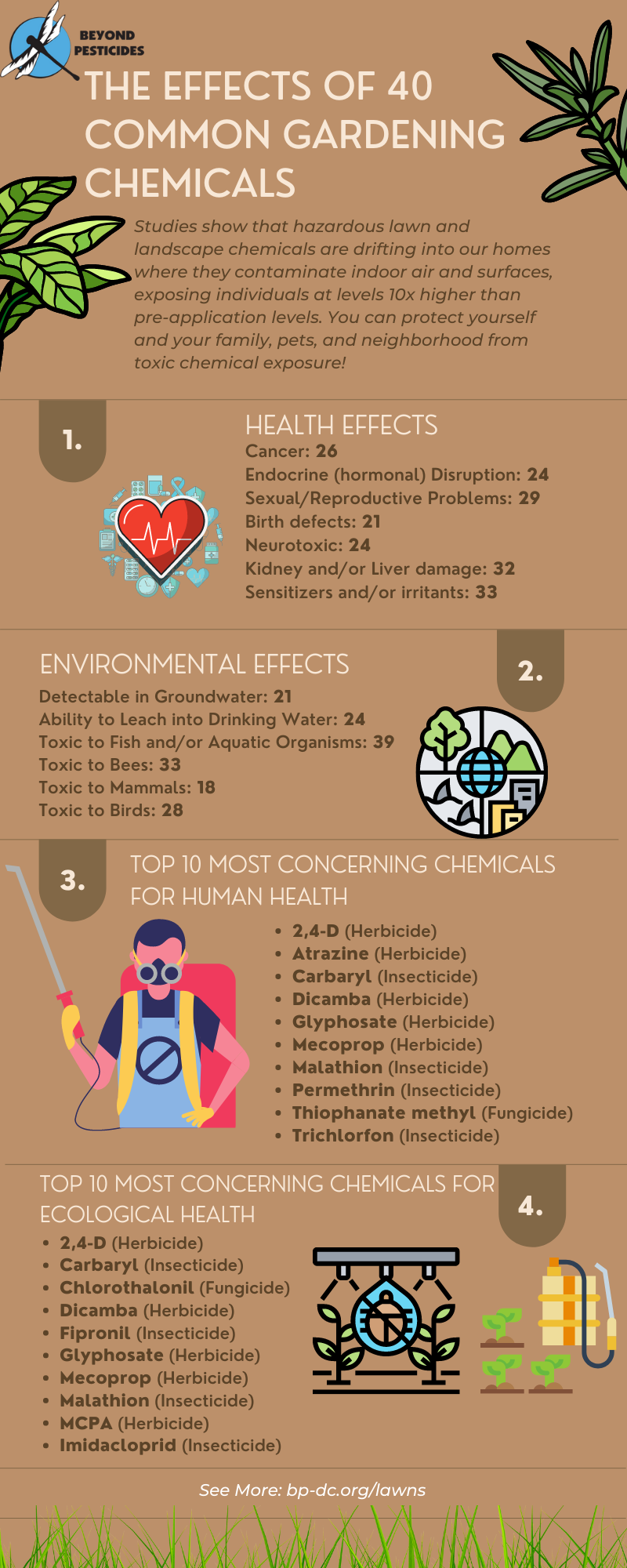

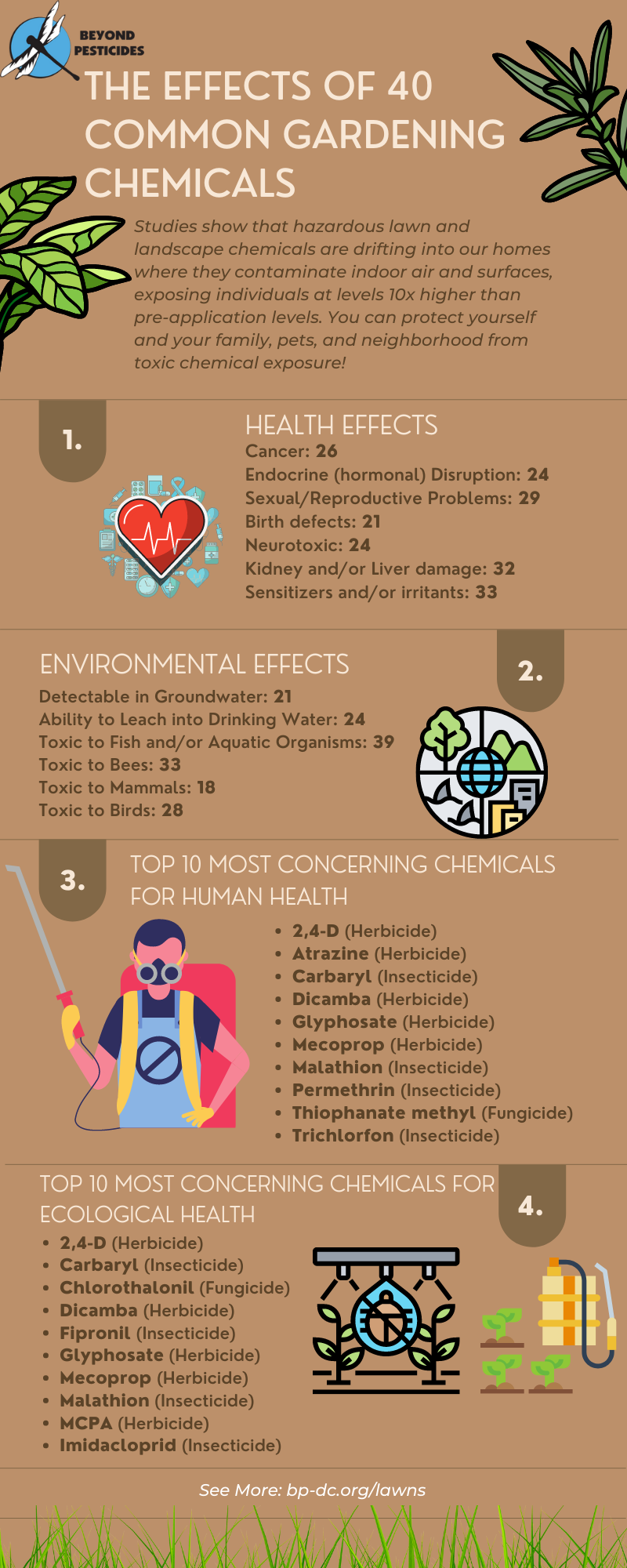

Petroleum-based synthetic pesticides harm health and the environment with both immediate and long-term effects. To know what chemicals to avoid, the â40 Most Commonly Used Lawn and Landscape Pesticidesâ factsheets (on health and environmental effects) simplify the science on pesticides hazardous to people, pets, and the environment. Additionally, our herbicide analysis is an extensive document of over 100 nonorganic (conventional) and organic products with specified health and environmental effects. The chemicals in the analysis include: Â

Why Avoid These Synthetic Chemicals?

To Protect Yourself, Your Family, and Your Pets

To Protect Yourself, Your Family, and Your Pets

- *Pesticides have many uses in homes and communities without comprehensive public knowledge about the harm that they cause. A growing body of evidence in the scientific literature (documented in Beyond Pesticides Pesticide-Induced Diseases Database) shows that pesticide exposure can adversely affect neurological, respiratory, immune, and endocrine systems in humans, even at low levels.

- *Children are especially sensitive to pesticide exposure because they (1) take up more pesticides (relative to their body weight) than do adults, and (2) have developing organ systems that are more vulnerable to pesticide impacts and less able to detoxify harmful chemicals.

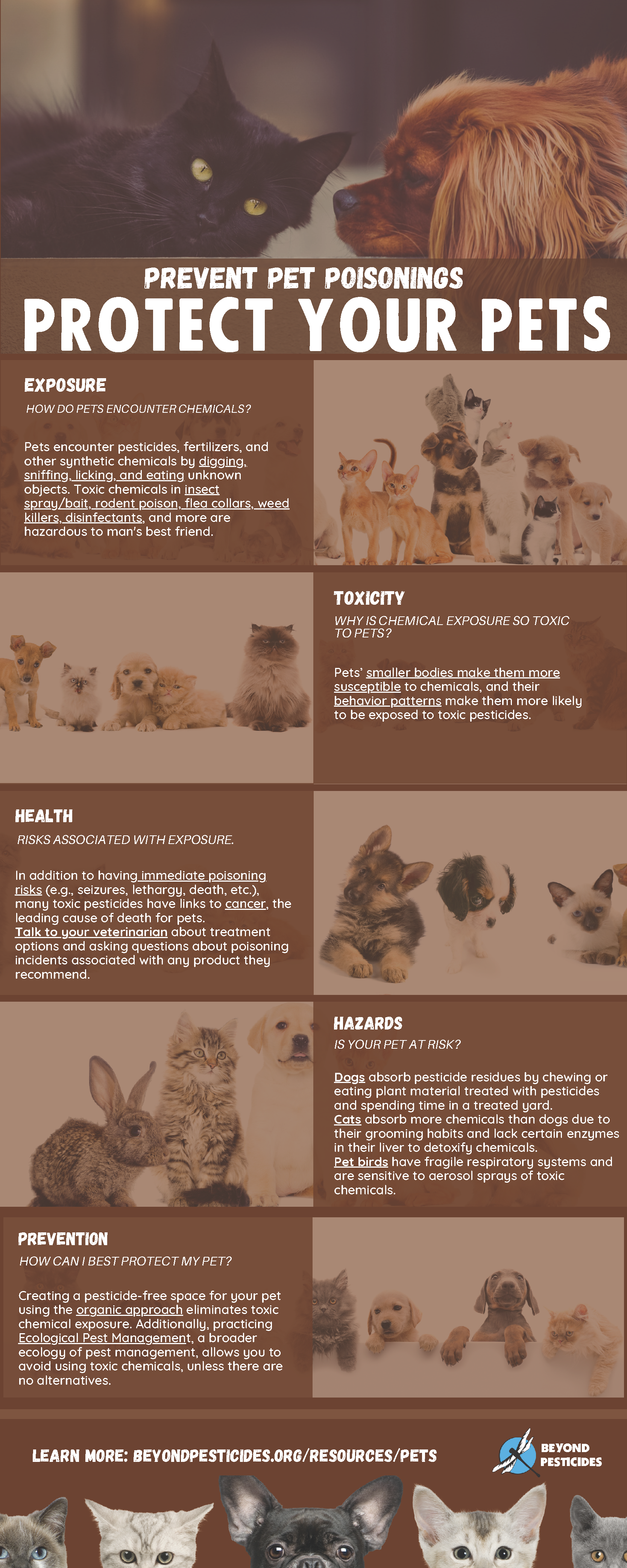

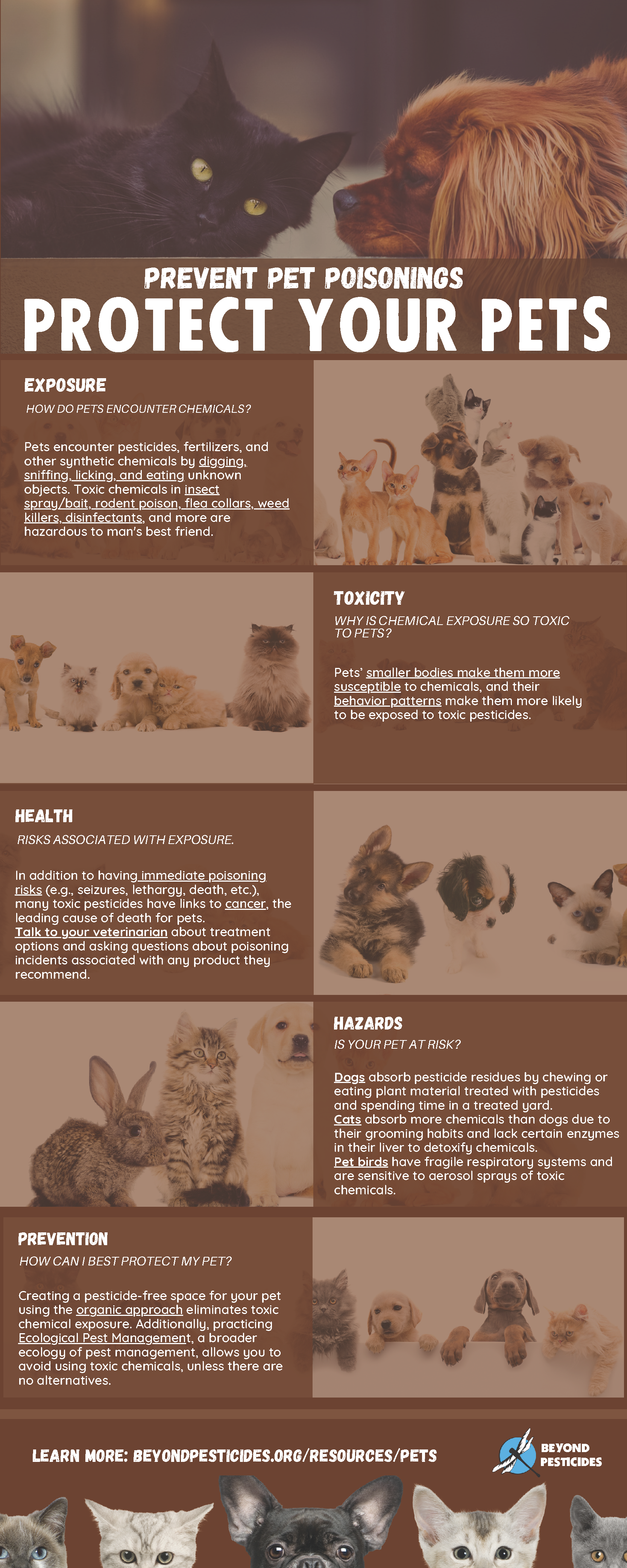

- *Furthermore, pets encounter pesticides by digging, sniffing, licking, and eating unknown objects. Toxic chemicals in insect sprays and baits, rodent poison, flea collars, weed killers, disinfectants, and more are also hazardous to our companion animals.

To Protect the Bees, Butterflies, and Other Pollinators

As bees, butterflies, bats, and other pollinators suffer serious declines in their populations, we urge people and communities to plant a pesticide-free habitat that supports pollinator populations. We provide information to facilitate this in our BEE Protective Habitat Guide. Become a beekeeper in your own backyard: Backyard Beekeeping: Providing pollinator habitat one yard at a time!

Urban Areas

- Pollinators: Significantly more pesticide residues are present in urban bumblebees that forage in nonorganic landscapes during April. However, honey bees kept on organic urban farms are less stressed from pesticide exposure.Â

Suburban/Exurban/Rural Areas

- Pollinators: Bees in suburban environments remain at risk of pesticide exposure from contamination of areas in which they forage and breed due to toxic weed control, pesticide use on crops, and animal pest treatments on farms. Garden pesticide products and contaminated ornamental plants sold in garden centers play a key role in spreading pesticides through suburban areas. A study from the University of Sussex reveals that 70% of bee-attracting plants sold at a range of garden centers have traces of neonicotinoids. Researchers urge suburban farmers and gardeners to, in addition to adopting soil health practices, swap synthetic pesticides with natural predators, like ladybirds or lacewings, and the use of physical methods, such as hand-removal of pests, and netting or sticky traps.

To Protect Birds, Especially Song and Migrating Birds

Neonicotinoids are a class of highly toxic insecticides that are systemic and move through the vascular system of the treated plant, contaminating pollen, nectar, and guttation droplets and indiscriminately poisoning insects, birds, and soil and aquatic organisms. Seeds are often coated with neonicotinoids and plants are drenched with the chemical. However, birds can eat the poisoned seeds as a food source, causing many adverse effects, including effects on reproductive function and egg formation, and even death. For more information on the dangers of neonicotinoid-coated seeds, see Beyond Pesticidesâ short video Seeds That Poison.

To Protect Beneficial Organisms and Microorganisms In and Around the Soil

Wildflowers, native shrubs, and trees, as well as urban green spaces, provide important habitats for beneficial organisms (e.g., worms, ants, beetles, etc.) and microorganisms (e.g., bacteria and fungi). Synthetic fertilizers and toxic pesticides threaten their survivability, reproduction, and distribution of essential nutrients. Additionally, plants grown in chemically-treated areas are more vulnerable to parasites and pathogens. The adoption of organic land management practices, like planting pollinator-friendly plants and cover crops, and using organic mulch for weed suppression, create healthier plants that are less vulnerable to disease and infestation, and more resilient.

Urban Areas

- Many insects are the victims of the global insect apocalypse or population decline. Much research attributes the recent decline to several factors, including pesticide exposure. Broad-spectrum pesticides indiscriminately kill pests and nontarget organisms alike, as their ubiquitous use contaminates soils, even in untreated areas.

- In addition to insects, the soil microbiome is essential for the proper functioning of the soil ecosystem. The microbiome is home to ecological communities of microorganisms living and working together. Toxic chemicals damage the soil microbiota by decreasing and altering biomass and microbiome composition (diversity). Pesticide use contaminates soil and results in a bacteria-dominant ecosystem, as these chemicals cause “vacant ecological niches, so organisms that were rare become abundant and vice versa.” Â

Suburban (Rural) Areas

- One of the most concerning consequences of soil pesticide contamination is the impact on organisms, including beneficial insects and microbes. Conventional farming technologies promote the use of pesticides that directly and indirectly affect soil organisms.

- Soil biology can change due to the presence of synthetic chemical pollutants like pesticides. Studies find some current-use pesticides induce changes in soil properties that re-release soil-bound chemicals into the ecosystem, contributing to contamination. Long-term or legacy contamination has resulted from the failure to regulate so-called stable chemicals that would bind to soil and remain immobileâthus beginning the continuing multigenerational poisoning from now-banned chemicals, like organochlorines, including DDT(its breakdown contaminant DDE) and chlordecone. Various studies find that glyphosate use stimulates soil erosion responsible for soil-based chemical emergence, harms the gut microbiota of honey bees, and destroys habitats for organisms like the monarch butterfly.

Spring Cleaning without Harmful Disinfectants

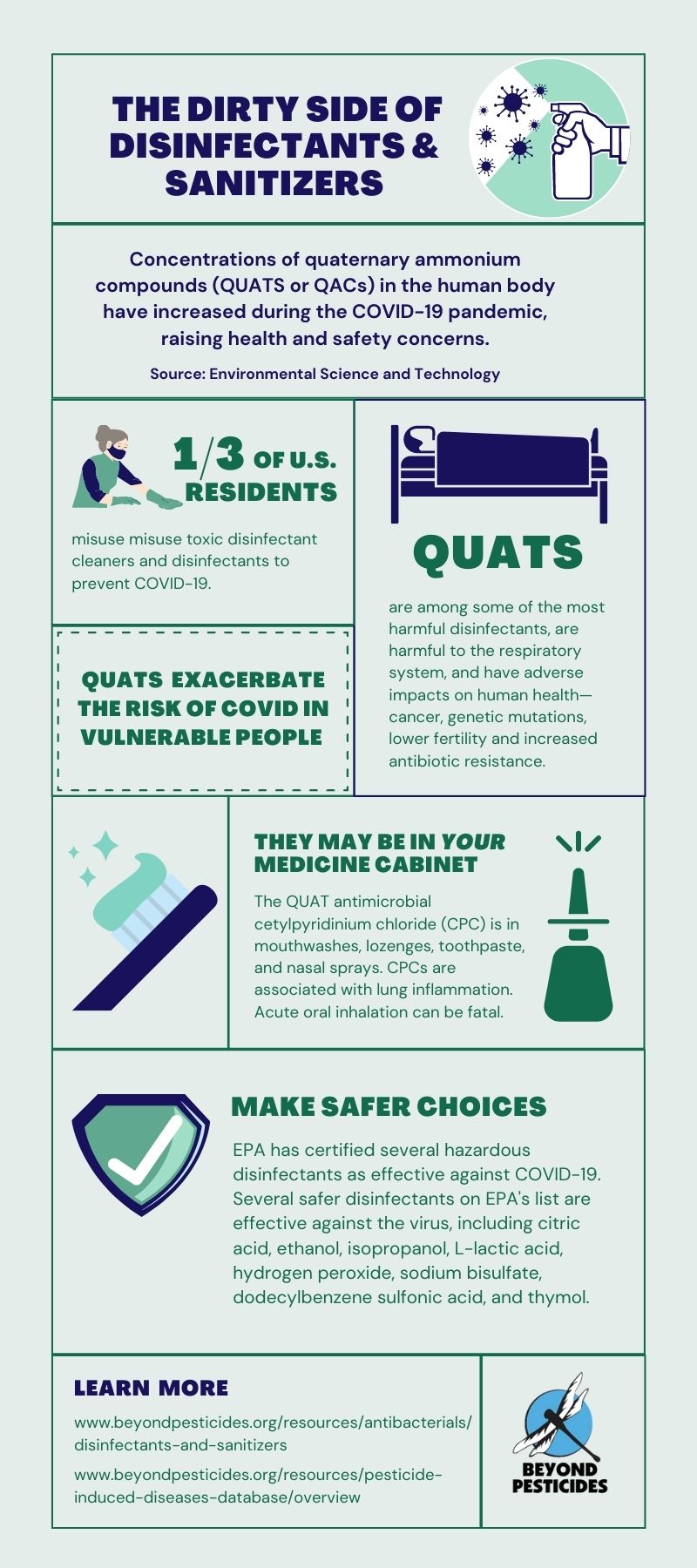

With spring cleaning upon us, many household disinfectants pose a risk to human, animal, and ecosystem health. To mitigate this hazard, advocates, including Beyond Pesticides, promote practices that eliminate toxic, synthetic chemical use by switching to organic and least-toxic pesticides to mitigate further risk.

Avoid Indoor Toxins

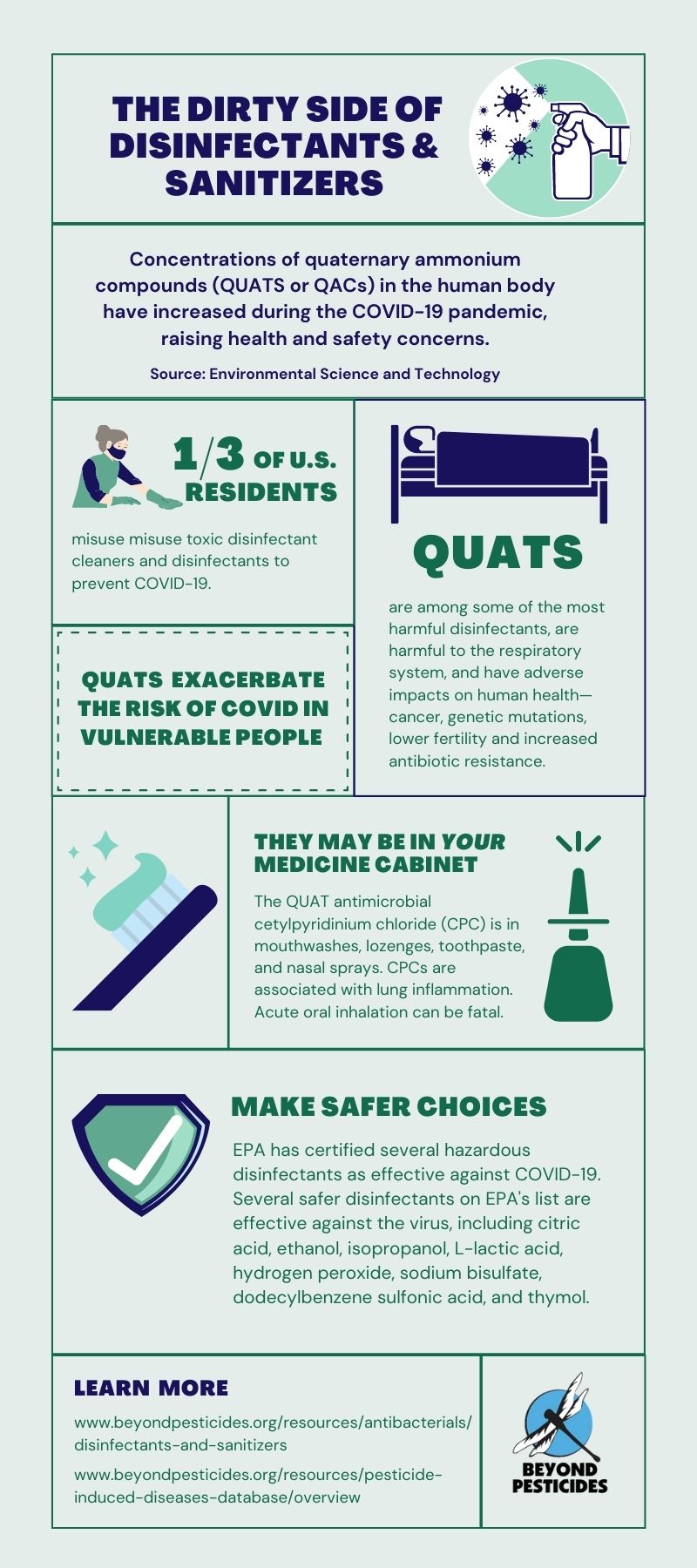

Exposure to disinfectant products containing toxic chemicals, such as chlorine bleach, peroxyacetic acid, quaternary ammonium compounds (quats), phenolic chemical compounds (i.e., cresols, hexachlorobenzene, and chlorophenols), sodium dichloro-s-triazinetrione, and hydrochloric acid, are associated with a long list of adverse effects, from asthma to cancer. All of these chemicals can harm the respiratory system, with some quats shown to cause mutations, lower fertility, and increased antibiotic resistance. Many of these toxic disinfectants are harmful via more than one exposure route, as ingestion and inhalation also trigger potentially more harmful effects. Although chemical disinfectants kill viruses, bacteria, and other microbes via cell wall and protein destruction, they can also irritate and destroy the mucous membranes in animal and human respiratory and digestive tracts upon ingestion or inhalation. This exposure can lead to death in extreme cases.

People who have a preexisting condition or are of advanced age, who may have a weakened immune or respiratory system, are more vulnerable to the effects of the Covid-19 virus. Many of the products approved as disinfectants have negative impacts on the respiratory or immune system, thus reducing resistance to the disease. When managing viral and bacterial infections, chemicals that exacerbate the risk to vulnerable individuals are of serious concern. The Centers for Disease Controlâs (CDC) report on an increase in poison control calls due to disinfectant misuse notes that a majority pertained to bleach products, a 62% increase in 2020, with a total disinfectant-related call increase of 108.8% between 2019 and 2020. We urge people to recognize that it is important during public health emergencies involving infectious diseases to scrutinize practices and products very carefully so that hazards presented by the crisis are not elevated because of the unnecessary threat introduced by toxic chemical use.

For more information on safe disinfectants, visit Beyond Pesticidesâ webpage on Disinfectants and Sanitizers.

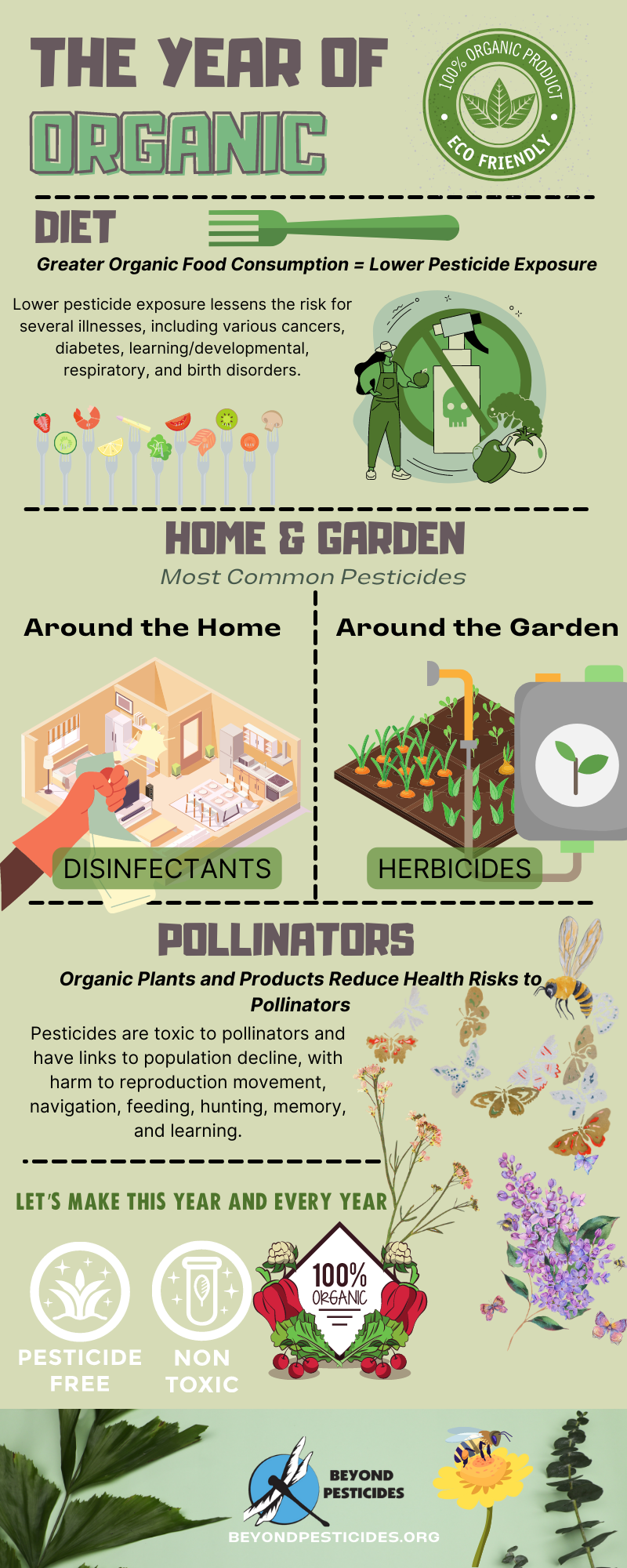

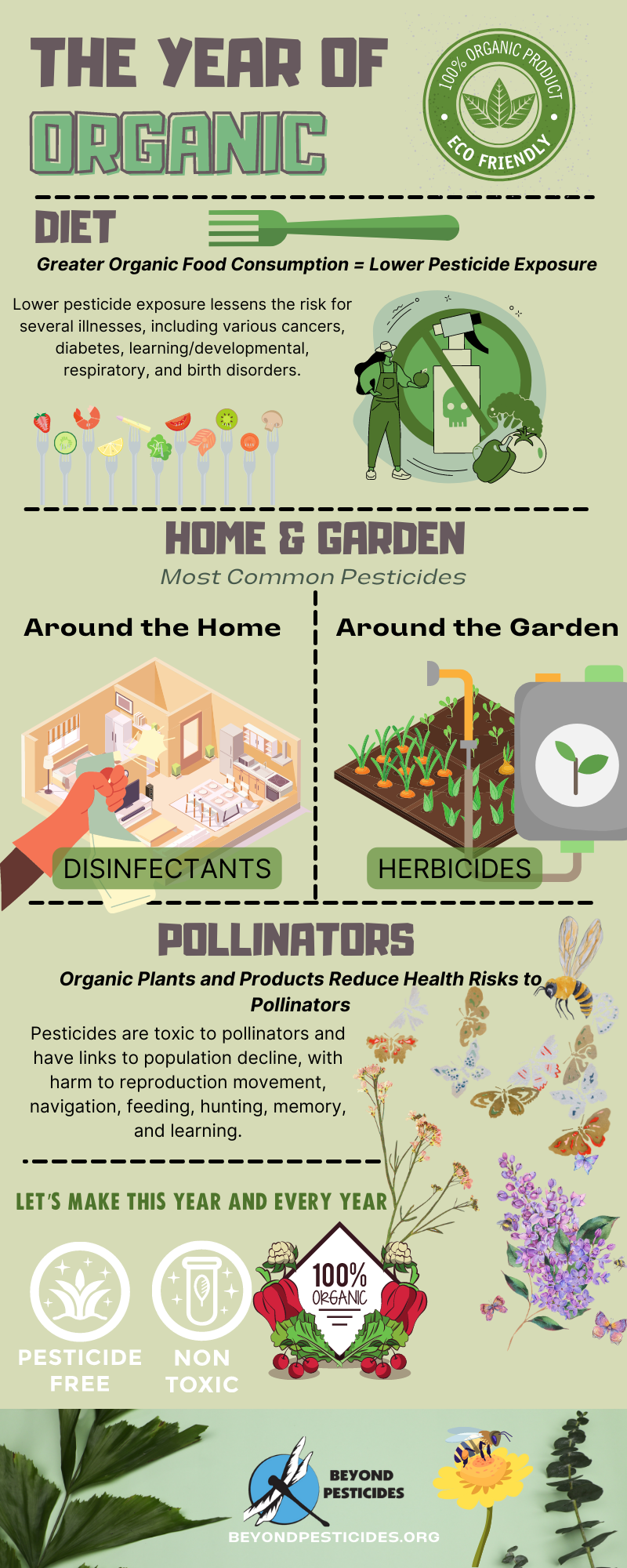

The Year(s) of Organic Solutions: The Safer, ORGANIC Choice

Following the organic/Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) label helps guide individuals to the organic-compatible, least-toxic products, safer choice products. There are two established lists of organic materials and products in âProducts Compatible with Organic Landscape Management:â

Following the organic/Organic Materials Review Institute (OMRI) label helps guide individuals to the organic-compatible, least-toxic products, safer choice products. There are two established lists of organic materials and products in âProducts Compatible with Organic Landscape Management:â

* The National List of Allowed and Prohibited Substances of the Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA), and

* The U.S. Environmental Protection Agencyâs list of exempt pesticides, Section 25(b) of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA).

Residential

Some of the products you may need for your garden include seeds, potting soil, mulch, tools, fertilizer/soil supplements, and compost. For most small-scale gardeners, pest problems can be contained with simple removal (scout the insects and remove them). If you decide to use a product to manage pests, do not be fooled by products labeled as âsafeâ or ânaturalâ (these products may contain nonorganic âinertâ ingredients that may be toxic). In general, organic-compatible products will display an OMRI ListedÂź seal on their labels, but not all products that meet organic standards have this seal. This same caution applies to fertilizers and potting soil as well. One of the great things about gardening at home on a small scale is the potential to create all the material needed for soil health through simple composting of kitchen scraps and yard waste.Â

When planting an organic garden, Beyond Pesticides offers a guide on how to âGrow Your Own Organic Food,â including a resource page on steps to take before planting Grow Your Own Organic Food â Beyond Pesticides. Companies and Nurseries that Grow and Distribute Organic Seeds and Plants can be found in our Seed and Plant Directory Brochure.

If there is a problem with weeds taking over yards and gardens, Beyond Pesticides offers a guide on how to “Read Your Weeds,” which identifies weeds in your lawn and suggests nontoxic, least-toxic, solutions. You can always check Beyond Pesticidesâ suggestion for managing lawns and buildings at ManageSafe: Least-Toxic Control of Pests in the Home and Garden. Additionally, Beyond Pesticidesâ webpage on the Ecological Management of Invasive Species is a great resource for broad weed management. Know your soil chemistry and biology with simple tests from land grant universities. For instance, clover is considered a typical turf weed (although more people are seeding microclover into lawns to provide nitrogen) that thrives in soil with low nitrogen levels, compaction issues, and drought stress. Many plants that are considered weeds have beneficial qualities (e.g., dandelions for bees). Try to develop a tolerance for some âweeds.â

Organic does not mean expensive, whether related to food or land management. As land management practices result in increased soil health, the microbial life in the soil cycles nutrients naturally and reduces the need for expensive fertilizers. Regarding organic food, Beyond Pesticides offers a guide on how to buy organic on a budget, âThe Real Affordability of Organic Food.” Buying organic produce whenever possible is always an option. On how to find and purchase organic products and why organic is about more than eliminating pesticide residues in the food and includes the protection of farmworkers and the environment in its production practices, visit the Beyond Pesticides webpage âBuying Organicâ and âEating with a Conscience.â

Community

Many urban areas have community gardens where one can get an individual plot for gardening. Community gardens in some urban environments have transformed the landscape and the community itself. Our Parks for a Sustainable Future program provides in-depth support for community land managers in transitioning public green spaces to organic landscape management. Contact Beyond Pesticides and we will collaborate with you to start two organic demonstration sites in your community at no charge, with the goal of providing the training and experience necessary for your parks department staff to transition all public areas in your community to these organic practices. Dozens of communities in all regions of the country already have organic communities where local parks, playing fields, and greenways are managed without unnecessary toxic pesticides and fertilizers. This is an opportunity for your community to address the three existential crises (to which petrochemical pesticides and fertilizers contribute) that we must all work to resolveâhealth threats, biodiversity collapse, and the climate emergency.

Read about some successful community gardens in New York City from Beyond Pesticides’ Pesticides and You journal. If you want to get your hands dirty but do not have the space or the desire to start a garden, see if there are any community-supported farms near you that could use your helping hands-on weeding or other projects.

Check Out Beyond Pesticidesâ Spring into Action page to further educate yourself on safer gardening practices around your home and community.

All unattributed positions and opinions in this piece are those of Beyond Pesticides.

Source: Beyond Pesticides                          Â