11

Dec

USDA Supports Expansion of âOrganicâ Hydroponically-Grown Food, Threatening Real Organic

Update: This Daily News is updated to address the organic status of the company cited in the piece, Merchantâs Garden. The article now indicates that the company is certified as organic under a different name (Merchantâs Garden Agrotech) than the name used in the USDA press release. As a result, their name did not appear in USDA’s Organic Integrity Database (OID) at the time of the original Daily News and Action of the Week posting. USDA updated OID on December 8, 2023, the same day that it received a complaint on this matter from former National Organic Standard Board chair Jim Riddle. The critical focus of the piece remains the same: It is not disclosed to consumers on food products labeled “organic” when that food or ingredients are grown hydroponically. Beyond Pesticides, as indicated in the article, views hydroponic as a conventional growing practice that does not meet the spirit and intent of the organic system, as defined in the Organic Foods Production Act.Â

(Beyond Pesticides, December 11, 2023) U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) Secretary Tom Vilsack announced on November 27, 2023 funding that appears to be supporting the expansion of âorganicâ hydroponic, an approach to food production that has been criticized by the vast majority of the organic community as a process that violates foundational organic principles. The funding, under USDAâs Rural Business and Value-Added Producer Grants program, is intended to assist in financing an expansion of rural businesses, including 185 projects worth nearly $196 million. Organizations representing organic producers and consumers have told the USDAâs National Organic Program that hydroponic food production, as a form of conventional chemical-intensive agriculture, does not meet the standards of soil-based food production required for USDA organic labeling. Currently, federal law does not require that hydroponically produced food be labeled, leaving consumers unable to distinguish production practices at the point of sale.Â

One of the projects highlighted in the USDA announcement states, âMerchantâs Garden LLC is a hydroponic and aquaponic farm in Tucson, Arizona. The company will use a $250,000 Value-Added Producer Grant to expand marketing and sales of prepackaged salad mixes to help them become a local supplier of organic leafy greens for southern Arizona.â However, Merchant’s Garden’s website does not make any organic claims for its produce, so advocates question why USDA is promoting this hydroponic/aquaponic producer as “organic.”

Beyond Pesticides has said: âTaxpayer dollars should not used to finance a hydroponic/aquaponic operation that does not comply with the Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA). If products from this operation are to be sold as âorganic,â it will cause harm to producers who comply with OFPA. It will also deceive consumers who purchase organic products believing that such products are produced in healthy, fertile soil, as required by the organic law and regulations. To the extent that hydoponic operations supplant soil-based (real) organic operations, these subsidies negate the climate and biodiversity benefits of organic agriculture.â

The Organic Foods Production Act, at 6513(b), requires that all organic crop production operations submit and follow organic plans that âshall contain provisions designed to foster soil fertility, primarily through the management of the organic content of the soil through proper tillage, crop rotation, and manuring.â The same section of OFPA goes on to state, âAn organic plan shall not include any production or handling practices that are inconsistent with this chapter.â

It is widely understood that organic farms support soil health, help sequester carbon dioxide, and avoid the use of materials like soluble nitrogen fertilizers that contribute many times as much warming potential as carbon dioxide. Beyond Pesticides advocates that USDAâs financial support should go to new and transitioning organic farms.

By decisive vote in 2010, the USDAâs National Organic Standards Board determined that hydroponic and aquaponic operations are inconsistent with OFPA and do not qualify for organic certification. Under the law, the National Organic Program (NOP) is required to determine whether Merchantâs Garden LLC complies with section 6513(b) of the Organic Foods Production Act and whether the operation intends to sell their hydroponically-grown products as âorganic.â If the operation does not comply, NOP is required to ensure that it is not certified organic.

Historically, perhaps the most important principle of organic production is the âLaw of Return,â which, together with the rule âFeed the soil, not the plantâ and the promotion of biodiversity, provide the ecological basis for organic production. (Sir Albert Howard. The Soil and Health: The Study of Organic Agriculture (1940), and An Agricultural Testament (1947).) Together, these three principles describe a production system that mimics natural systems. The Law of Return says that we must return to the soil what we take from the soil. Non-crop organic matter is returned directly or through composting plant materials or manures. To the extent that the cash crop removes nutrients, they must be replaced by cover crops, crop rotation, or additions of off-site materials when necessary.

The dictum to âFeed the soil, not the plantâ reinforces the fact that soil is a living superorganism that supports plant life as part of an ecological community. Soil organisms are not fed to plants in isolation to have them process nutrients for crop plants. The soil is fed to support a healthy soil ecology, which is the basis of terrestrial life.

Finally, biological diversity is important to the health of natural ecosystems and agroecosystems. Biodiversity promotes balance, which protects farms from outbreaks of damaging insects and disease. It supports the health of the soil through the progression of the seasons and stresses associated with weather and farming. It supports our health by offering a diversity of foods.

A 2010 National Organic Standards Board report embraces these foundational principles but also contrasts organic production and âconventionalâ chemical-intensive agriculture. At the time of the passage of OFPA, the organic communityâs characterization of soil as alive was viewed with amusement by the âconventionalâ agriculture experts, who saw soil as a structure for supporting plants, while farmers poured on synthetic nutrientsâand the poisons that had become necessary to protect the plants growing without the protection of their ecological community. Interestingly, organic producers at that time compared conventional agriculture to hydroponics.

Conventional agriculture has now learned something about soil lifeâenough to promote some use of cover crops despite continued reliance on petrochemical nitrogen. On a parallel track, practitioners of hydroponics have learned the value of biology in their nutrient solutions. However, in both cases, the lessons have not been completely understood. This is made very clear from the hydroponics industry explanation that âbioponicsâ (non-sterile hydroponics) depends on biological activity.

It is the case that bioponics relies on biological activity in the nutrient solution to break down complex molecules and make them available to the plants. It is also true that the nutrient solution in bioponics has an ecologyâas all biological systems do. However, the hydroponics industry repeatedly calls this a âsoil ecology,â although it is merely an artificial mimic of soil ecology and a reductionist approach to manipulating nature.

A quote from the Omnivoreâs Dilemma (2006) by Michael Pollan can provide some perspective on the importance of organic as envisioned by the early adopters of the practices and the drafters of OFPA:

To reduce such a vast biological complexity to NPK [nitrogen-phosphorous-potassium] represented the scientific method at its reductionist worst. Complex qualities are reduced to simple quantities; biology gives way to chemistry. As [Sir Albert] Howard was not the first to point out, that method can only deal with one or two variables at a time. The problem is that once science has reduced a complex phenomenon to a couple of variables, however important they may be, the natural tendency is to overlook everything else, to assume that what you can measure is all there is, or at least all that really matters. When we mistake what we can know for all there is to know, a healthy appreciation of oneâs ignorance in the face of a mystery like soil fertility gives way to the hubris that we can treat nature as a machine.

The ecological system of a hydroponic nutrient system is described by the hydroponics industry to be more like a fermentation chamberâa means of processing plant nutrientsâthan the soil ecosystem of an organic farm. The three principles cited above are explained in further detail below:

The Law of Return. In a soil-based system, residues are returned to the soil by tillage, composting, or mulching. In a bioponics system, the residues may be composted; the residue is not returned to the bioponic system, closing the loop. The inputs that are typically identified in bioponics include many agricultural productsâanimal-based compost, soy protein, molasses, bone meal, alfalfa meal, plant-based compost, hydrolyzed plant and animal protein, composted poultry manure, dairy manure, blood meal, cottonseed meal, and neem seed mealâand these are produced off-site, with no return to their production system. While most organic growers depend on some off-site inputs, most of the fertility in a soil-based system comes from practices that recycle organic matter produced on-site. The cycling of organic matter and on-site production of nutrientsâas from nitrogen-fixing bacteria and microorganisms that make nutrients in native mineral soil fractions available to plantsâis essential to organic production. The Law of Return is not about feeding plants but about conserving the biodiversity of the soil-plant-animal ecological community.

Feed the soil, not the plant. The description of the bioponics system and case studies reveal how much bioponics relies on added plant nutrients. These nutrients may be made available through biological processes, but they are added to feed the plants, not the ecosystem. Here is an example of a case study of bioponic tomatoes:

After planting the seedlings in this growing media, it is necessary to add supplemental nutrition throughout the growing cycle (approximately one year). About once per week, solid and liquid nutrients are added to the growing media. Some fertilizers can be applied through the irrigation lines because they are soluble enough and will not clog the lines. The use of soluble nitrogen fertilizers is limited because of their high costs, for instance, for plant-based amino acids. [S]odium nitrate. . .will be used as a lower cost nitrogen source. Soluble organic-compliant inorganic minerals, such as potassium and magnesium sulfate, are also added through the irrigation system.

Biodiversity. The definition of âorganic productionâ in the organic regulations requires the conservation of biodiversity. As stated in the National Organic Program Guidance on Natural Resources and Biodiversity Conservation (NOP 5020),

The preamble to the final rule establishing the NOP explained, â[t]he use of âconserveâ [in the definition of organic production] establishes that the producer must initiate practices to support biodiversity and avoid, to the extent practicable, any activities that would diminish it. Compliance with the requirement to conserve biodiversity requires that a producer incorporate practices in his or her organic system plan that are beneficial to biodiversity on his or her operation.â (76 FR 80563) [Emphasis added.]

Under this guidance, while the hydroponics industry may say it is not diminishing soil and plant biodiversity, certified organic operations must take active steps to support biodiversity. On a soil-based organic farm, many practices supportâfrom crop rotations to interplanting to devoting space to hedgerows and other nonproductive uses. These practices are also used by organic farmers producing food in greenhouses. However, bioponics is a monocultural environment that does not support biodiversity.

Letter to Secretary Agriculture Tom Vilsack:

On November 27, you announced the release of funds from the USDA Rural Business Development and Value-Added Producer Grant Programs to assist in the financing or expansion of rural businesses. In total, 185 projects worth nearly $196 million are being funded to create new and better market opportunities for agricultural producers.

One of the projects highlighted in the USDA announcement is very troubling. The announcement states, âMerchantâs Garden LLC is a hydroponic and aquaponic farm in Tucson, Arizona. The company will use a $250,000 Value-Added Producer Grant to expand marketing and sales of prepackaged salad mixes to help them become a local supplier of organic leafy greens for southern Arizona.â However, Merchant’s Garden’s website does not make any organic claims for its produce, so it is curious that USDA is promoting this hydroponic/aquaponic producer as “organic.”

Taxpayer dollars should not be used to assist a hydroponic/aquaponic operation that does not comply with the Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA) to sell products as organic. If products from this operation are to be sold as organic, it will cause harm to producers who comply with OFPA. It will also deceive consumers who purchase organic products believing that such products are produced in healthy, fertile soil, as required by the OFPA and regulations. To the extent that hydroponic operations supplant soil-based (real) organic operations, these subsidies negate the climate and biodiversity benefits of organic agriculture.

The Organic Foods Production Act, at 6513(b), requires that all organic crop production operations submit and follow organic plans that, âshall contain provisions designed to foster soil fertility, primarily through the management of the organic content of the soil through proper tillage, crop rotation, and manuring.â The same section of OFPA goes on to state, âAn organic plan shall not include any production or handling practices that are inconsistent with this chapter.â

The Earth needs many more real organic farms that support soil life, help sequester carbon dioxide, and avoid the use of materials like soluble nitrogen fertilizers that contribute many times as much warming potential as carbon dioxide. USDAâs financial support should go to new and transitioning organic farms.

By decisive vote in 2010, the USDAâs National Organic Standards Board determined that hydroponic and aquaponic operations are inconsistent with OFPA and do not qualify for organic certification. The National Organic Program (NOP) must use its accreditation system to determine whether Merchant’s Garden LLCâs certifier, Where Food Comes From Organic, complies with section 6513(b) of the Organic Foods Production Act. If the certification agency does not comply with OFPA, NOP should revoke their accreditation for certification of organic crops.Â

Thank you.

Letter to U.S. Representative and Senators:

On November 27, Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack announced the release of funds from the USDA Rural Business Development and Value-Added Producer Grant Programs to assist in the financing or expansion of rural businesses. In total, 185 projects worth nearly $196 million are being funded to create new and better market opportunities for agricultural producers.

One of the projects highlighted in the USDA announcement is very troubling. The announcement stated, âMerchantâs Garden LLC is a hydroponic and aquaponic farm in Tucson, Arizona. The company will use a $250,000 Value-Added Producer Grant to expand marketing and sales of prepackaged salad mixes to help them become a local supplier of organic leafy greens for southern Arizona.â However, Merchant’s Garden’s website does not make any organic claims for its produce, so it is curious that USDA is promoting this hydroponic/aquaponic producer as “organic.”

Taxpayer dollars should not used to assist a hydroponic/aquaponic operation that does not comply with the Organic Foods Production Act (OFPA) to sell products as organic. If products from this operation are to be sold as organic, it will cause harm to producers who comply with OFPA. It will also deceive consumers who purchase organic products believing that such products are produced in healthy, fertile soil, as required by the OFPA and regulations. To the extent that hydroponic operations supplant soil-based (real) organic operations, these subsidies negate the climate and biodiversity benefits of organic agriculture.

The Organic Foods Production Act, at 6513(b), requires that all organic crop production operations submit and follow organic plans that, âshall contain provisions designed to foster soil fertility, primarily through the management of the organic content of the soil through proper tillage, crop rotation, and manuring.â The same section of OFPA goes on to state, âAn organic plan shall not include any production or handling practices that are inconsistent with this chapter.â

The Earth needs many more real organic farms that support soil life, help sequester carbon dioxide, and avoid the use of materials like soluble nitrogen fertilizers that contribute many times as much warming potential as carbon dioxide. USDAâs financial support should go to new and transitioning organic farms.

By decisive vote in 2010, the USDAâs National Organic Standards Board determined that hydroponic and aquaponic operations are inconsistent with OFPA and do not qualify for organic certification. The National Organic Program (NOP) must use its accreditation system to determine whether Merchant’s Garden LLCâs certifier, Where Food Comes From Organic, complies with section 6513(b) of the Organic Foods Production Act. If the certification agency does not comply with OFPA, NOP should revoke their accreditation for certification of organic crops.Â

Please tell Secretary Vilsack to ensure that all certifiers are consistently preventing organic certification of operations that do not comply with section 6513(b) of the Organic Foods Production Act.

Thank you.

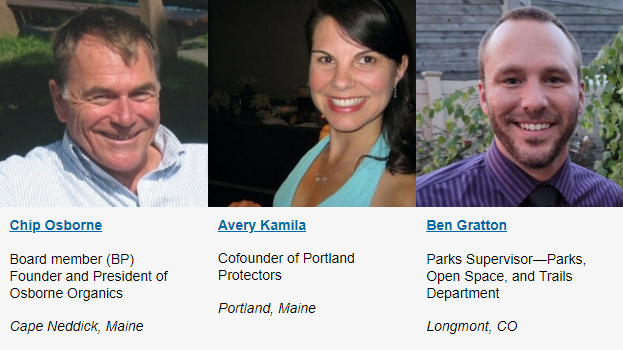

Chip Osborne

Chip Osborne